Most of us learned to read a long time ago and now do it so effortlessly we may assume, wrongly, that learning to read occurs naturally, like learning to walk or talk. We may harbor the false assumption that if we surround students with books, instill a love of reading, and model the process for them, they'll pick it up on their own. Conversely, when they struggle to read, we might assume they have a mental deficiency that requires intervention from a specialist.

Research suggests otherwise. According to Louisa Moats (1999), a prominent reading researcher, reading comprises many complex mental processes that we only acquire through direct instruction. Moreover, as reading researcher Richard Allington (2013) notes, with effective instruction and relatively small doses of additional support to help students decode the printed word, as many as 98 percent of students could read on grade level. And yet, according to the most recent results of the National Assessment of Educational Progress, fully 34 percent of 4th graders in the U.S. read at below basic levels and only 35 percent demonstrate proficient or higher performance (U.S. Department of Education, 2019).

So how do we get closer to that 98 percent? It requires educators learning and applying what international researchers Castles, Rastle, and Nation (2018) note has become settled science that ought to put an end to the "Reading Wars." Thanks to decades of exhaustive research about how students translate print into meaning, we know some key insights on how teachers can help them master these processes.

Key Insights from Reading Research

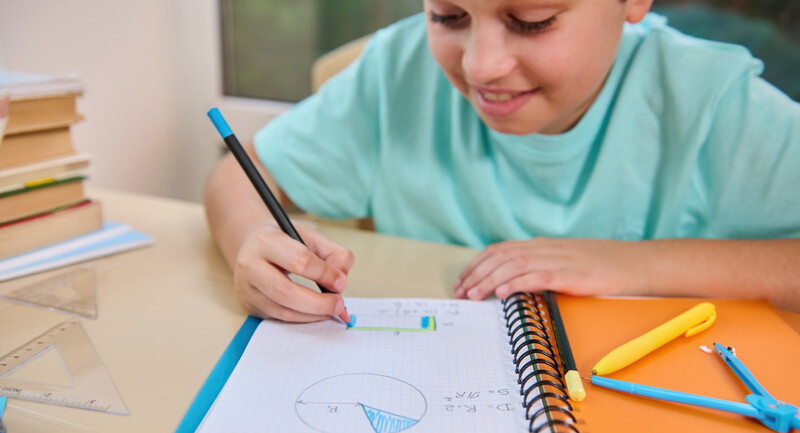

Reading doesn't come naturally to many students. Reading requires connecting abstract symbols (letters) to sounds (consonants, vowels, syllables, and words) and connecting words together to make meaning. These connections are far from intuitive, so students don't arrive at them naturally or through immersive experiences. Instead, teachers need to help students see the "code" behind these sound-symbol connections—namely, that every letter represents a sound and every spoken word can be captured with written letters (Moats, 1999).

Decoding is the fundamental building block of reading. As you read this, your brain is engaged in the same sound-symbol matching processes you learned as a child (Castles et al., 2018). It just happens so quickly that you don't notice it. The ability to link symbols and sounds, in fact, accounts for up to 80 percent of the perceived variance in students' ability to read (Moats, 1999). Children who make these connections readily can "sound out" new words and, thus, read increasingly more complex texts with many long-term benefits.

Developing fluency requires the right kind of practice. For students to develop reading fluency, there's no substitute for practice—making repeated sound-symbol connections through reading and writing (Castles et al., 2018). Although some phonics programs insist students practice these connections by decoding nonsense syllables, researchers tend to view this practice as, well, nonsense, with limited transferability to authentic reading (Allington, 2013).

Fluency is key to comprehension. Our brains can only juggle so much information at once. The more mental energy students must expend sounding out words or deciphering their meaning, the less bandwidth they have left to comprehend what they're reading. As students decode more automatically, they can spend more time thinking about what they're reading (Castles et al., 2018). They find reading less tedious and more enjoyable, which contributes to what Stanovich (1986) called the "Matthew Effect"—good readers read more, becoming better readers, while poor readers eschew reading and become, in relative terms, poorer readers.

Students need to be taught comprehension strategies. Expert readers draw upon background knowledge to anticipate where texts may be going, ask reflective questions about what they're reading, and use context clues to figure out new vocabulary (Castles et al., 2018). While these comprehension strategies may seem intuitive, students need to learn them and see them modeled (Moats, 1999).

Complementary, Not Competing

Perhaps the biggest takeaway from the science of reading is that contrary to popular misconception or the so-called Reading Wars, decoding and comprehension are complementary, not competing, approaches to reading instruction (Castles et al., 2018). A study involving 268 mostly minority, low-income 1st graders found that students whose teachers provided direct instruction in decoding demonstrated achievement approaching national averages for both decoding (43rd percentile) and comprehension (45th percentile), compared with far lower average scores (at the 29th and 33rd percentiles, respectively) for students whose teachers offered little direct instruction in decoding (Foorman et al., 1998).

While these insights aren't new to researchers, many elementary teachers have not been exposed to them. According to an analysis from the National Council on Teacher Quality, only 37 percent of U.S. preservice education programs teach the science of reading to aspiring teachers (Ross, 2018). Moreover, many preservice reading instructors have only a cursory understanding of reading research; according to a study of college instructors responsible for teaching reading in 30 different universities, only 54 percent of them could correctly identify a definition of phonemic awareness and just 50 percent could explain rules of phonics, such as why some words start with a c and others with a k (Joshi et al., 2009).

Leaders shouldn't assume elementary teachers arrive in their schools ready to apply the science of reading in their classrooms. Nor should they assume off-the-shelf reading programs alone will shore up knowledge gaps, especially because, as a recent review of the most widely used reading programs discovered, such programs often don't reflect many key principles from the science of reading (Schwartz, 2019).

Teaching is a profession, and like all professions, it requires acquiring and applying expertise to solve challenges. The good news is that by learning and applying expertise from the science of reading, ordinary teachers can do something extraordinary: help nearly all students learn to read at grade level.