Collective teacher efficacy is all the rage these days. We read about it in education publications, talk about the related research at meetings and conferences, and do our best to put it into practice in our schools. In my book Collaborative Leadership: 6 Influences That Matter Most (Corwin, 2016), I rank collective teacher efficacy as one of the most important influences on school leadership today.

The reason that collective efficacy has become such an important focus for school leaders and teachers is simple: It can have a marked positive impact on student learning. It's important to understand, however, that collective efficacy doesn't just happen, especially in schools that are beset by low morale and top-down mandates. It requires a great deal of trust, which must be built over time, and an intentional effort by educators to buck the status quo. Tschannen-Moran and Barr (2004) define collective efficacy as the "collective self-perception that teachers in a given school make an educational difference to their students over and above the educational impact of their homes and communities." I often look at it this way: Whereas self-efficacy is the confidence we have in ourselves, collective efficacy is the confidence we have in our group to make a difference.

There are a lot of factors involved in getting to that point. As Goddard and coauthors (2004, p. 3) found, "The connections between collective efficacy beliefs and student outcomes depend in part on the reciprocal relationships among these collective efficacy beliefs, teachers' personal sense of efficacy, teachers' professional practice, and teachers' influence over instructionally relevant school decisions." What this means to me is that the road to collective efficacy—the way in which educators take the reins and see they can change the status quo—may be just as important as the destination.

A Time of School Crisis

When I was a school principal, there were a few years when we felt like everything was coming to an end in public education. Our small school district in upstate New York was experiencing millions of dollars in budget cuts, there were teacher and administrator layoffs, enrollment was down, and many families were moving out of state due to the high cost of living.

On top of all that, the district had to close a one-classroom-per-grade-level school, and the school that I led was faced with the challenge of absorbing the whole student population from that school. All of this took place at the height of the NCLB-driven accountability era, which had its own demoralizing effects.

I knew I couldn't take on all of these challenges on my own, nor did I want to, because I had an amazing staff that I loved and could count on. The Zulu have the word Ubuntu, which means "I am because we are." That is certainly how I felt about the staff I led at the time, and I believe the sentiment works perfectly for discussions around collective teacher efficacy.

During this trying time, many of us felt as though we had lost our value as educators because our voices no longer seemed to be listened to in educational conversations at the state and national level. Collective teacher efficacy happens when teachers have "influence over instructionally relevant school decisions" (Goddard et al., 2004), and that certainly didn't seem to be happening. Within our school, I began to hear teachers express concerns about low morale—a sign for me that teachers didn't feel they were meaningfully engaged in their work.

The Power of Chart Paper

Our school had a Principal's Advisory Council that met once a month, made up of school leaders and a representative from each grade level and specials area. Although I was the principal, I did not typically run the meeting. That was left up to two cochairs, who often challenged my thinking. The council was meant to focus on our building climate, so what better place to have a discussion around morale?

At our meeting in October 2012, I asked if I could start with an activity. I spoke to the committee members about morale being low in the school, and suggested we dig deeper into this situation together. There was an easel with chart paper in the front of the library, where the meeting was always held, and markers and stickers sat on each table. I asked each member of the committee to go up to the easel and write every reason they could think of for why we had low morale. After they finished what turned out to be a lengthy list, I handed each of them three stickers and asked them to put their stickers next to the issues that they felt contributed most to low morale. They could put all their stickers next to one issue or distribute them among the items on the list.

Out of a few issues with multiple stickers, the one that had the most stickers by far was that teachers felt they no longer had a voice in their own professional development. This was not surprising to me because, with all the policy changes at the time, our professional development days were taken up by discussion of state and district accountability measures. We were always scrambling to meet external mandates rather than focusing on our own priorities.

This, in retrospect, was where we began our quest for collective efficacy. Together as a PAC, we decided that our school would start with taking control of some of our own professional learning and development.

Flipping the Faculty Meeting

Through subsequent conversations at the meeting, we determined that the focus of our professional development effort would be on providing effective feedback, an area where we agreed that we struggled as a faculty, but also one that we had the internal capacity to address. We also decided that flipping our regular faculty meetings might be the best way to start. A flipped faculty meeting is a process where staff and the principal co-construct a goal for the meeting together, and then a few days before the meeting takes place, the principal (or another involved leader) shares a resource, such as a blog, article, or video, that models how to meet that goal.

About three days before our faculty meeting, I crafted an email to all staff explaining the flipped process, our PAC activity, and our determination. I attached an article by Grant Wiggins from the most recent issue of Educational Leadership on providing effective feedback. I asked the faculty to read the article and bring to the meeting evidence of the feedback they provide to students so we could share our expertise with each other. Additionally, I offered a couple of questions about the article to ponder while reading it. One thing we know about self-efficacy is that not everyone feels confident in every part of their job, so flipping a meeting structure in this manner allows people to gain some surface-level knowledge before the meeting. They can then take a greater role in discussing issues at the meeting, which in turn builds both collective knowledge and self-confidence. Remember, as Goddard noted, "teachers' personal sense of efficacy" is important to collective efficacy. Through that individual effort, teachers can come together and build on the confidence each has, which will sometimes result in collective efficacy.

At the next faculty meeting, we discussed the article and shared best practices. We worked on a common language and a common understanding of effective feedback practices. After that meeting, as I visited classrooms, I could see a transfer of learning from what we explored together at the meeting, and I saw how many teachers were incorporating better feedback practices into their instruction. For me, this was an example of collective efficacy. We worked on an issue, learned together, and then some of that learning changed what was happening in classrooms.

The Collective Efficacy Cycle

Sometimes collective efficacy in a school develops in this way. It comes from a moment when we realize we need to improve a situation and take collective action. My school's collaborative efforts to provide more effective feedback to students ultimately resulted in academic and social-emotional gains for students, which in turn further boosted our sense of collective efficacy.

But leaders and teachers don't have to wait for a crisis to start efforts to build collective teacher efficacy. Even at times when the bottom doesn't seem to be dropping out, educators can work to build collective efficacy and improve the learning environment for students by looking collaboratively at their grading practices, creating restorative justice programs, or finding strategies to improve their teaching of conceptual understandings to students. What matters is that teachers are able to take charge of an element of teaching and learning and see the difference they can make through working together.

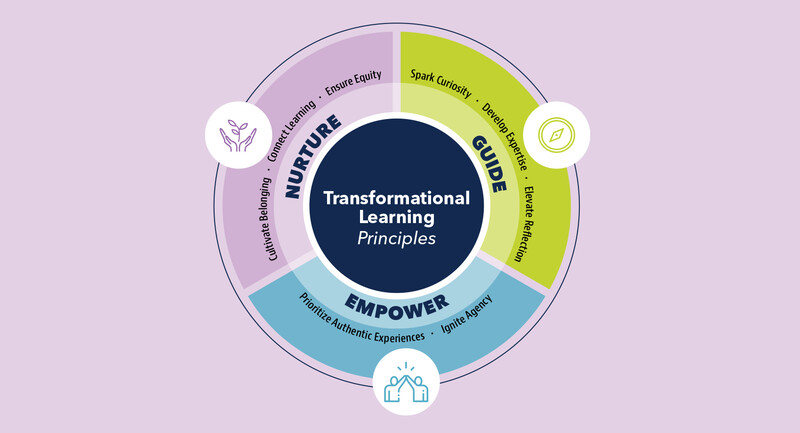

To help educator groups start working toward collective efficacy, I've created, from a variety of sources, a diagram of the elements involved in the process (fig. 1). The work begins by co-constructing a goal together, which means ensuring that all participants have an authentic voice in the process. Then team members work together to examine and test solutions and examine evidence of impact (Hattie, 2012). If strategies do not work, the collective efficacy process necessitates refining ideas and trying again. Lastly, team members should take into account the simple pleasures of working together through a challenge—and take time to celebrate their success (Donohoo, 2013).

Figure 1. A Collective Efficacy Cycle

Adapted from Knight (2007), Donohoo (2013), DeWitt (2018)

Another important point that's not on this figure: To build collective teacher efficacy, leaders need to make sure team members understand why they are coming together in the first place. This may sound obvious, but more times than I can count, I've witnessed situations where people are asked to be a part of the group, or are voluntold to do so, and they really have no idea why they are there. It's very difficult to build collective teacher efficacy when people do not understand why they are in the room.

Below are some suggestions to prevent that from happening. At the outset of an initiative, make sure you:

Define why each member is a part of the team.

Define the expectations of being on the team.

Co-construct a goal together around the initiative you're focused on.

Assign duties for each member of the team.

Promote and support discourse among the team.

Banding Together

In that difficult stretch during my tenure as a principal, our school community faced many challenges stemming from administrative changes and regulatory mandates. But we did not let this fracture our building-level community. This reminds me of something Michael Fullan told me a few years ago: "Just because you're stuck with their policies doesn't mean you need to be stuck with their mindset." As a staff, we decided we would band together to take control of some of our learning and create a new mindset on what we could achieve, starting with the practice of providing effective feedback. I didn't realize it at the time, but we were indeed building collective teacher efficacy.