Last year at the ASCD Annual Conference, I met Bonnie St. John, an African American champion skier and an inspirational speaker whose topic is educating students with disabilities. I met Bonnie at the door of the empty conference hall where in a few hours she was to speak to an overflow audience. She persuaded the guard to let us in (we were supposed to enter through a guest entrance, but she was the general session speaker), then she sprinted down the graduated stairway to the stage. There she began pacing, reciting poetry to get the feel of the sound system. It was an impressive introduction to a woman whose leg amputation occurred at 5 years of age.

In her speech, Bonnie talked about the time that her mother, a single mom and a school principal, brought home to her a brochure picturing a one-legged skier. Not that her mother expected Bonnie to learn to ski—they lived in San Diego, after all—but that she wanted her to realize the possibilities in life. As her skiing record shows, Bonnie took to the idea.

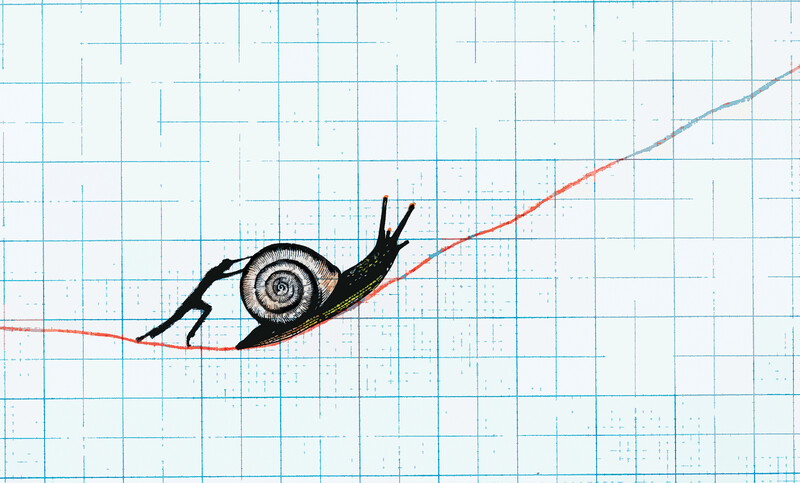

Challenges and possibilities are the twin themes of this issue on “Improving Instruction for Students with Learning Needs.” Thirty years ago, terms such asmainstreaming andleast restrictive environment first became familiar to educators. Today the talk is of response to intervention, universal design, andadequate yearly progress. If anything, the challenges and possibilities are larger than ever.

Greater expectations. Talk to most parents of children identified as having a disability (see p. 91), and you will probably hear that they want educators to see past their child's disability. Like all parents, they want their schools to meet their child's special needs, and they don't want their child labeled or stigmatized. Years ago, parents had to plead for children with Down syndrome to be taught to read and for students with autism to be educated with their classmates. No wonder advocates today feel that if they don't push the system, their children won't receive the education services they deserve.

In recent years, the goal for children with disabilities has shifted from improving access to education to improving student performance. The goal today is for all students to be proficient on state content standards for the grade in which they are enrolled. The NCLB requirement to disaggregate data by subgroup means that when it comes to educating students with special needs, schools face higher expectations than they have ever faced before. And as critics of NCLB note, 100 percent proficiency is a goal that no country's education system has ever achieved. Even those who applaud NCLB acknowledge the difficulties of implementation.

Ableism. Author Thomas Hehir (p. 9) introduces a concept that may be new to many—ableism. Like racism and sexism, ableism discriminates. It does so in two ways: Either it expects too little and therefore treats those with disabilities as incapable; or it expects too much, asking students with disabilities to perform exactly as their nondisabled peers do without accommodations or special services.

Hehir suggests that the purpose of special education is to “maximize the opportunities to participate while minimizing the impact of the disability.” Assuming that there is one right way to learn, read, walk, talk, paint, or take a test is the root of inequity, he says. The requirement to include students with disabilities in standards-based reform holds promise, but high-stakes tests should not be the only means through which students can demonstrate what they know and are able to do.

The deficit mode. Beth Harry and Janette Klingner (p. 16) discuss the difficulty of defining and identifying some disabilities. Unlike physical conditions that are more objectively verifiable, many learning disabilities are assessed through observation, judgment, or ambiguous tests. The intertwining of race with perceptions of disability is deeply embedded. As a result, students in minority groups historically have been overrepresented in some special education categories and underrepresented in others. Thus some students are shunted away from opportunities while others fail to get the help they need.

Response to Intervention (RTI) is a different way of looking at learning problems. Instead of first identifying students as having a learning disability, this technique offers various supports and lessons to address deficiencies first. Only if the student fails to respond to repeated interventions does the school team consider special placement. This practice, along with the strategies suggested by the authors in this issue, could benefit the general education population as well as students who need special placement.

The promise of research. Several of our authors shed new light on the causes of such disabilities as autism (p. 29), attention deficit disorder (p. 22), and reading problems (pp. 68 and 74) including dyslexia. Some day, brain research will give us clearer insight about the mysterious complexity of human ability and disability. In the meantime, educators' continuing challenge is to give all kids the knowledge and skills they need to live a full and rich life.