In principle, we know that we should value what students say. But what if a student completely misinterprets the story he or she is reading? A 5th grader I'll call Adam provides a case in point. Adam, who received special education services, was part of a pullout summer school literature discussion group serving seven struggling readers. I observed this group while visiting Adam's school one summer as part of a professional development team supporting teachers who worked with struggling middle-grade readers. An experienced classroom teacher I'll call Max was facilitating this particular literature discussion group. During one discussion, Adam was reading a fable that opens with the sentence, “A miller and his son set off to market to sell their donkey, leading the beast behind them.” Hearing the wordbeast, Adam hypothesized, “The donkey may be very mean, so they don't want to ride him.”

Because nothing else in the story suggests that this donkey was mean, many teachers would correct Adam by offering a definition of the wordbeast that made more sense, such as a beast of burden. Even if they did not directly say he was wrong, they would evaluate his response in such a way that he would know it was wrong.

But Adam's teacher, Max, did not step in to correct Adam. What I observed in the discussion shows how students can find their way to text-based critical thinking when an astute teacher resists yanking away “wrong” interpretations.

In Adam's case, because the teacher did not step in, one of the other 5th graders responded directly:THOMAS: Beast can mean a lot of things. It can mean, like what Adam is thinking, big and mean and stuff, butbeast can also just mean that he's big. . .ADAM: I know, but they're selling him: “Leading the beast behind them.”THOMAS: Yeah, maybe they need the money.

Thomas called Adam's idea into question, but his words did not have the effect of a teacher's words; Adam did not feel as though he had to change his mind. Instead, he took what Thomas said as an invitation to prove his point, pointing out that the (presumably mean) donkey-beast was being sold. He continued with this line of reasoning for several more conversational turns, unswayed by Thomas's counterarguments.

To the casual observer, Thomas looks like the more sophisticated reader, because he knew several meanings ofbeast and could identify the one seemingly most connected to the story. But notice that Thomas did not back up his belief with textual evidence, whereas Adam did. I argue that Adam was publicly displaying more sophisticated reasoning about what he was reading than Thomas was.

Why didn't the teacher endorse Thomas's interpretation? Perhaps because such a move almost inevitably would have undermined Adam's reasoning process and his confidence as a reader exploring the text. Adam's hypothesizing was actually in line with how schema theory conceptualizes the process of reading comprehension. As Rumelhart (1981) explains, “Readers are said to have understood the text when they are able to find a configuration of hypotheses (schemata) which offer a coherent account for the various aspects of the text” (p. 9). Adam's guess that the donkey was being sold because of its meanness offered him a coherent account of the text, and from Adam's perspective, hewas comprehending. With a teacher correction, Adam might have learned the alternate meaning of beast, but he presumably would not have learned why this meaning fit the text better.

Beyond One Knower

In most classrooms, the teacher acts as the “primary knower” who already knows the answer to the questions he or she asks and knows the “real” meaning of texts under discussion. Students are “secondary knowers” whose ideas can only become legitimate in classroom conversation when the primary knower—the teacher—bestows that legitimacy (Berry, 1981). Teacher-student exchanges often follow a pattern of teacher initiation:Teacher: Which way did the wolf go to granny's cottage?STUDENT: He took a shortcut through the forest.TEACHER: That's right.(Nassaji & Wells, 2000).

This kind of teacher question is completely different from one I might ask in ordinary conversation, where I genuinely need to know the answer. In this pattern of interaction, the student has no independent authority to evaluate the text; the focus is on matching the teacher's interpretation.

But if we believe that reading is about critical thinking, this approach to teaching comprehension is problematic. Interpreting a text should involve making decisions about how different aspects of the text fit (or fail to fit) with the hypotheses a reader has begun to generate. If I, as primary knower, step in to inform you that you are wrong, I inadvertently short-circuit that thinking process. Even “leading” students to evidence that supports our adult understanding of a text may make them reluctant to go out on a textual limb in developing their own hypotheses.

In the discussion involving Adam and Thomas, their teacher, Max, did not act as the primary knower. Max realized that Adam's understanding was nonstandard, but he still did not force his own interpretation on the class. He maintained that students have good reasons for every textual hypothesis they hold; as a result, he was not as interested in getting the students to accept his meaning of the story as he was in unpacking their reasons (and having them unpack one another's reasons) for the hypotheses they were generating. Every comment that he made was dedicated to this end.

Indeed, no one participant in that conversation acted as the primary knower. Instead, Adam and his peers acted as possible knowers. Student ideas—standard or nonstandard—fully had the floor, and students could evaluate the text and one another's ideas about the text. For example, when Max refused to either validate or dismiss what Adam had said, Thomas picked up the slack. Had Max taken sides, that opportunity would have been lost.

When Max spoke again, he did so to bring the other students in the group into the conversation, asking each child in turn “What does the wordbeast make you think of?” Five of the seven in the group leaned toward Adam's nonstandard understanding, but Max still did not step in with an authoritative definition. Instead he said, “Clearly we have more than one understanding of the word beast. Maybe if we read a little bit further on, it will help us clarify what the author's understanding of beast is.” The students needed to look to the text, not to the teacher, to resolve the disagreement. And they did.

Authentic Reasons to Probe the Text

Up to this point, both Adam and Thomas had applied some important textual strategies. Adam drew on inferential reasoning as he hypothesized that the donkey was being sold because it was mean. Thomas appeared to rely on prior knowledge to propose that beast could have more than one meaning, and that bigrather thansavage was the more logical meaning here.

But this reference to prior knowledge was not enough to convince Adam—or the others—to adopt Thomas's interpretation. Perhaps as a result, Thomas subsequently began citing textual evidence directly to support his ideas. When the miller set his son astride the donkey in the story, Thomas seized on this fact:THOMAS: If I was the miller and I knew that the donkey was dangerous, I wouldn't put my own kid on its back. I would put me.MAX: I'm hearing you saying that you're not necessarily comfortable with that idea, that you don't think that's what's going on.THOMAS: No! Because I'd rather have me get hurt than my own son.MAX: All right, well, let's hang onto that....Can everyone remember that?

Max restated Thomas's point, suggesting that he found it noteworthy, but he did not evaluate the hypothesis. Thomas remained deeply invested in convincing the others; he spoke up several more times to argue that Adam's interpretation was textually inconsistent, while Adam continued to resist such arguments.

Later in the story, after another student read the part where a passing merchant said, “How can the two of you ride on the poor skinny beast? You could carry him more easily than he can carry you!” (Pinkney, 2000, p. 38), Thomas clinched his argument, drawing on direct textual evidence. Adam remained unconvinced until another student—Alfredo—launched a textually consistent explanation for the sale of the donkey.THOMAS: If it was a beast, like it was very strong, it would have been able to carry both of them no problem! But he [the merchant] just said, “You could carry him more easily than he can carry you.”MAX: OK.THOMAS: So if he was bigger and had more muscle, he would be able to carry them no problem.ADAM: But why are they selling him?ALFREDO: They're probably selling him because he's skinny.ADAM: He's weak.ALFREDO: Yeah.ADAM: You can't ride him.ALFREDO: And they have no use for him.ADAM: Yeah, because you can't ride him two at a time. Because, as Thomas said, they passed a guy on horseback, and he said, “How can the two of you ride on that poor skinny beast?” And he's all skinny and stuff, so what's the use for riding a skinny and poor donkey?THOMAS: So you're changing your idea about a beast?ADAM: Yeah, it's not a beast.

After half an hour of intense discussion, Adam publicly relinquished his idea that the donkey was mean. When he said, “Yeah, it's not a beast,” he was acknowledging that the text was inconsistent with his previous view; this could not be a mean, beastly animal. And both boys were remarkably sanguine about the matter.

Shared Evaluation Pedagogy

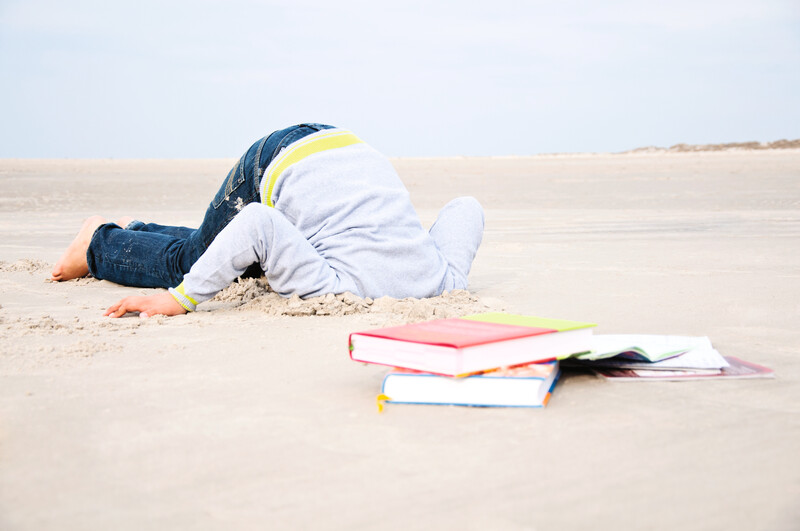

This example represents one of many times I observed the students in this group wrangling with one another and with the text. Their teacher's refusal to judge their ideas as right or wrong enabled the students to share responsibility for closely evaluating their own and one another's ideas. I call this kind of teaching and learning shared evaluation pedagogy (Aukerman, in press). No longer simply secondary knowers, these boys became possible knowers, with new reasons for engaging with the text, as outlined in Figure 1.

Who's Afraid of the "Big Bad Answer"?-table

Reasons that... | When the teacher is the primary knower | When students are possible knowers |

|---|

| Students speak up... | ...to be validated by the teacher | ...to convince others |

| Students listen to other students... | ...there is no clear reason to listen | ...to discern the credibility of alternative positions, strengthen their own case, and modify their hypotheses as necessary |

| Students read the text closely... | ...to figure out what the text means to the teacher | ...to discover (dis)confirming evidence for their own hypotheses and those of their peers |

But, however interested and engaged they are, will students actually become better readers through this kind of teaching? Don't they need to be corrected by the teacher and explicitly taught “better” ways of reading?

That all depends on your goal in reading instruction. If your goal is to get your students to arrive at a standard interpretation of a particular text, shared evaluation pedagogy may not serve your purposes very efficiently. When students pursue their ideas and assume substantial ownership over the conversation, they might never get to a common understanding of the big points you want them to take away. But if your goal is to develop critical readers for the longer term, evidence suggests that shared evaluation pedagogy can be tremendously powerful—and that what students learn in these conversations that assume there are no wrong answers serves them well even on tests that do require a “right” answer.

For example, I undertook a yearlong randomized study with several colleagues (McCallum, Aukerman, & Martin, 2003) at another school. We found that at this school, 5th graders in pullout discussion groups in which teachers used shared evaluation pedagogy realized an average growth rate in comprehension that was 1.5 times the growth rate of their classmates in a control group (as measured by the Qualitative Reading Inventory-II; Leslie & Caldwell, 1995). Students in the control group received strategy-based basal instruction from their general classroom teacher instead.

Almost all the students in the treatment and control groups were English language learners who had been identified as struggling readers—precisely the sort of “low achievers” often believed to need more explicit instruction in comprehension strategies than their higher-achieving peers (Stahl, 2004). But students in the shared evaluation pedagogy group did not receive explicit strategy instruction at all. Their growth as readers beyond that of the control-group students can probably be attributed to opportunities to thoroughly explore their textual hypotheses for purposes that mattered to them.

Taking students' ideas seriously—even when those ideas seem tangential, unsupported, or incomprehensible—is at the heart of shared evaluation pedagogy. There is more to this pedagogy than a respectful, nonevaluative stance toward student ideas; it is equally important to be, quite simply, a curious teacher. This means following up on precisely those ideas that most puzzle you, engaging students with one another's ideas, and monitoring your impulse to bring things back to the ideas that you consider most significant. When you listen most closely to what at first seems “wrong” to you, you may find, to your surprise, that your reading discussions turn out right.