Over the last 20 years, the education consulting group I work with has collaborated with multiple schools and districts looking to incorporate assessment practices that measure what matters to them. In some cases, the process went smoothly and these institutions' assessment systems now better reflect their mission and vision. But many districts faced unexpected implementation and sustainability challenges, not because the teachers and administrators couldn't do the work or because the assessments were low quality, but because those involved overlooked key moves that could set an assessment project up for success or inadvertently made missteps.

Given ever-pressing accountability concerns, it's understandable that school leaders may feel a sense of urgency to move quickly in launching a new system or may experience challenges while negotiating multiple factors around new assessments. Our experiences have shown us that when districts make three strategic moves when making changes to their assessment system, those changes are more likely to go smoothly—and endure.

1. Define What You Value and Keep It in View

A key feature of quality assessment design is alignment (Nitko & Brookhart, 2011). In effect, we know an assessment is good if it's structured so that students completing the assessment can provide strong evidence of mastering the identified learning targets. This is relatively easy to accomplish with content-based standards and skills. But when we start to assess other outcomes, like dispositions or habits of mind, it gets complicated because of their qualitative nature.

For example, suppose a district designs a challenging task to assess students' ability to persevere, but neglects to ascertain whether the task is easy or hard for students. Students who finish quickly will appear to lack perseverance but in fact may have misunderstood the task or found it too easy. Things can get even more complicated when designers want to assess multiple dispositions—such as creativity and critical thinking—in a single assessment. A quality like creativity has multiple meanings, and unless we take the time to anchor and illustrate our definitions and ensure everyone means the same thing when they talk about a quality or habit of mind, the assessment may not be measuring what the stakeholders want it to.

Schools and districts often use their mission or vision statements to define the district's focus, but they usually keep that work separate from assessment conversations. Explicitly articulating what is truly valued by a school community and then considering how those values are made manifest in assessments helps ensure that the work stays focused on what matters (Martin-Kniep, 2016).

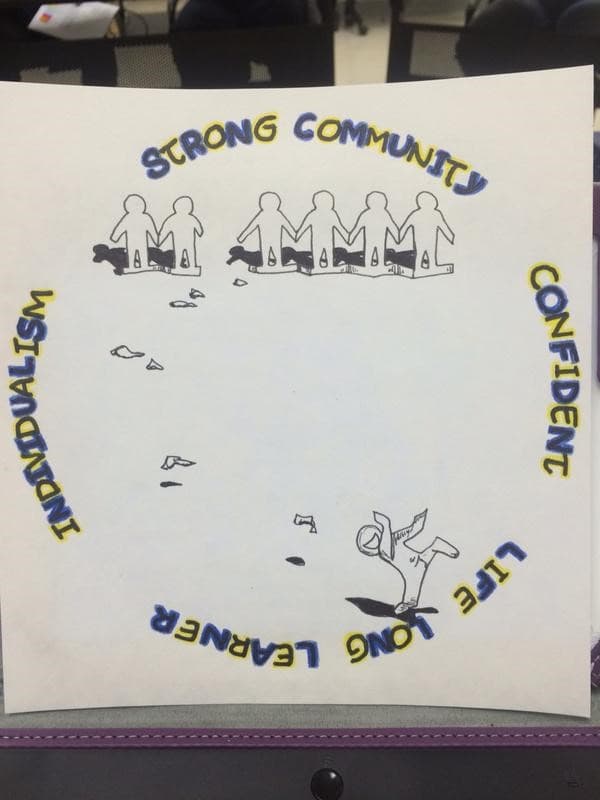

One way of clarifying outcomes before beginning any assessment work is to have school leaders assemble a team that represents the diversity of the district and broader community. After reviewing core documents such as the district's mission or vision, this group can be tasked with prioritizing desired outcomes. Teams may find it helpful to generate lists specifying "what it looks like" when students are demonstrating a particular quality—and what it looks like when students aren't demonstrating it. They might create an illustration that summarizes one or more of these outcomes.

An image an assessment team created to highlight key phrases from their district's vision.

This means that rather than focusing on mottos like "every child, every day," the team creates an image that expresses an outcome like passion or persistence. I've worked with teams doing assessment overhauls who created such an illustration; Figure 1 shows the image one group created based on key phrases from their district's vision (individualism, community, confident, lifelong learner). After adoption, these images can act like anchors or touchstones. They enable the group to evaluate success through a simple lens and answer questions such as:

- Does engaging in this assessment allow students to practice what really matters to us?

- Does this assessment give students evidence of how well they're learning what matters to them?

- Does this assessment give adults evidence to help us better understand students?

It's also helpful to have students on this team. When the group includes students, it's less likely to get bogged down in superlatives or the quest for the perfect phrasing and more likely to focus on getting greater clarity for all members of the school community.

There can be a lot of noise around assessment, even when it's learner-centered, authentic, and well-intentioned. Disciplined clarity through language or images understood by everybody can help cut through the noise to support non-negotiable priorities.

Find and Clarify Mixed Messages

Having a growth mindset is key to success in school and life. This message is common in districts across the United States, and is likely shared by most educators at all levels of K–12. Unfortunately, day-to-day practices often undermine it.

As assessments become increasingly learner-centered and reporting from the school to the home shifts from numerical scores to standards-based scales, schools are relying on rubrics for communication. But in many cases, rubrics unconsciously undermine the message we want to send about a growth mindset. It's not uncommon for students to compile a rich, meaningful portfolio and then be measured with a rubric that reduces their hard work to a score based on counting boxes, multiplying rows by columns, or other mathematical crimes that blur ratio and ordinal scales. Students frequently hear messages about a growth mindset, but they are required to self-assess with rubrics that use 4 to represent the highest score and that display the score range, left to right, as 4-3-2-1—suggesting that students should get it right from the beginning. Or, learners are asked to figure out the difference between a "detailed" (level 3) and "detailed and clear" (level 4) explanation.

Measuring what matters isn't always about big moves. If a school or district is considering implementing alternative assessments, some of the pre-work can include looking carefully at rubrics and checklists already in use and revising as needed so these rubrics align with what matters to the community. Leaders can ask teachers to review their tools and ensure that those tools support a growth mindset by making shifts like displaying rubric levels from low to high, using text descriptors instead of numbers, and focusing on what students did, not just what they did wrong. Figure 2 shows a rubric related to the disposition of academic honesty that communicates a growth mindset.

Figure 2. Example of a Growth Mindset Rubric on the Disposition of Academic Honesty

Another common mixed message relates to the larger issue of a country and schools' commitment to diversity. The march last summer involving white supremacists that led to violence and a death in Charlottesville, Virginia, brought into stark relief the fact that there's a lot of work to be done around building a healthy, multicultural society in America. While no single assessment can meet the goals of an anti-racist, culturally relevant education, small moves around representation in assessment can expand students' abilities to connect with others. Start by looking at current or future assessments, seeing whose perspectives are missing, and asking questions such as:

- Are authors of color referenced as experts on a range of topics beyond race and identity?

- Are teachers routinely using names and stories of people with backgrounds different from those of their students'?

- When students use texts for research, are they seeing work that reflects a diversity of perspectives and authors? Are they seeing reflections of themselves and windows onto the world? (Bishop, 1990)

- Are the assessment tasks accessible to all students?

Attending to issues of diversity and fairness in assessment—including explanations of historical or political events, names in word problems, experts cited, and even details like the book covers students see when doing research projects—can help schools reconcile the mixed messages that surface when schools say that students need to be prepared for a diverse world while primarily exposing them to familiar names and faces (Hess & McAvoy, 2014; Popham, 2006).

This work can sensitize teachers to their own assessment use and frame school leaders' feedback during and after the adoption of a new assessment. For example, an administrator might notice that a new alternative assessment asks students to consider diverse opinions, but that the texts students encounter outside of that one assessment reflect a single point of view or perspective. Sharing these findings with teachers or curriculum designers and providing time for them to revise or tweak their assessments can multiply the effect of the assessment without requiring a massive overhaul.

Include Students' Input and Perspectives

A principal once relayed an anecdote to me while we were scoring an assessment project focused on social and emotional learning. She had pulled together a group of students for a conversation about the schedule, and, after asking for permission to talk about something not on the agenda, one student blurted out, "I have no idea why you're making us do that feelings stuff. What's it for?"

That same year, we hosted an assessment conference that included a student-led panel. Without being prompted by adults, several students offered up that a constant diet of project-based assessments was unsustainable. One student added that it was exhausting to be constantly reflecting on her own thinking and identity, and that it was OK to give an "old fashioned" test occasionally.

In both cases, the student speaker identified what happens when even the highest quality assessment, designed and administered with the best of intentions, happens to students. A great deal of the shift away from conventional assessments toward more student-centered ones stems from our adult understanding that our own school experiences could have been improved by better assessments. This, at times, leads us to think that all students would want what we want, or to assume we understand the full implications to students of any proposed innovative assessment project.

For that reason, it's essential that any school or district looking to make shifts to their assessment system include student voice in the process. This doesn't require deferring to students in all things, but it does require acknowledgement that any assessment system that happens to students is weaker than one that happens with students. It doesn't require putting students at the table for psychometric conversations, but it could mean pulling together a student assessment panel to give feedback on proposed changes. (This practice has the added advantage of increasing the likelihood that designers will explain the goals, purpose, and design of their proposed assessment in clear, accessible language.)

Younger students can play a slightly different role by keeping assessment diaries or by joining the principal for lunch following the first day of a new assessment project to share what they think. In both cases, students can offer perspectives and opinions that adult designers may overlook.

When we incorporate assessments that matter to us as adults, it doesn't necessarily follow that they will matter to the students. At times, new assessments may make little sense to the students taking them. By listening to students, clarifying mixed messages, and having a shared understanding of what we value, we can make it much more likely that any new assessment will matter both to us and the children taking it. These actions also make it more likely that adopting alternative methods will proceed successfully and will lead to lasting change.