The possibilities of a new school year are endless. Just as the newly sharpened pencils, crisp notebooks, and shiny desks await their new users, the beginning of school offers a clean slate for learning. Unfortunately, this potential for new beginnings is often unrealized when it comes to math. Deeply held beliefs about ability paired with instructional and institutional practices that limit opportunities result in students (and teachers) embracing a number of math myths that simply aren’t true. The start of the school year is the perfect time to debunk one of the most powerful and damaging math myths that permeates our schools—the myth of “the math person,” or the widespread fallacy that math is an innate ability possessed by only a select few. It’s the supposition that you’re either “a math person” or you’re not, and that there are some learners who simply will never grasp mathematical concepts at high levels. It’s time to break this cycle of low expectations and adopt philosophies and practices that support all our students in realizing their math potential.

Unpacking Math Baggage

The first step in countering the myth of the math person begins with educators coming to terms with their own feelings about math. Many educators, particularly those at the elementary level, may not have been provided with opportunities to study math deeply in teacher preparatory programs and now find themselves in the uncomfortable position of having to provide instruction in a subject for which they themselves may have had negative prior experiences.

Teachers who lack confidence in the subject matter may find themselves “sticking to the script” and page-turning through textbooks rather than developing engaging lessons. The consequences of low teacher self-efficacy beliefs are powerful. Teachers who feel less effective in their abilities to teach a subject have been found to engage in deficit thinking, refer students to special education at greater rates, and experience more challenges with students from certain backgrounds, especially low-income students.

This cycle of underdeveloped math potential needs to be broken. The good news is that the opposite is also true: When teachers feel more positively about their own instruction and teaching abilities, they are more likely to positively influence student achievement, motivation, and behavior. They believe students are capable of positive change and are more likely to persist in working with students who are struggling academically.

It’s time to adopt philosophies and practices that support all our students in realizing their math potential.

We suggest that you take some time before the start of the school year to explore your own math story. Are you someone who believes they are “just not a math person?” Or, were you a math whiz who was awarded for your speed and accuracy in classroom competitions? Maybe you fall somewhere in between those two ends of the spectrum.

Whatever the case, think about how your own experiences with math shape the way you teach it. What is working well and what do you hope to improve? Exercise your own agency and seek what you need as a professional. Understand your own strengths and leverage them. Have courage as you explore your own areas of growth and discover new teaching practices, while giving yourself grace as you dispel misconceptions. If you have access to an instructional coach, email them and make an appointment to chat.

Building a New Philosophy in Your Classroom

The myth of the math person is so widespread that a term was coined to describe individuals’ relationships with math—a term called “math identity.” Math identity can be thought of as the beliefs and attitudes that students hold about their ability to successfully complete mathematical tasks. These belief systems are shaped by prior experiences, including the type of instruction students received, their perceived successes or failures, and the relationships they had with both teachers and peers in the math classroom.

Take a moment to consider the variability in the math identities of your learners. Some have endured hours of remediation outside the classroom, while others have been quickly validated for calculating at high speeds. Still others may have plodded along through their math coursework, perhaps compliant but not engaged.

Before jumping into the first math lesson of the school year, start by asking students about their experiences with math. In a method of expression most meaningful to them, have students share their answers to the following questions:

- Do you like math? Why or why not?

- What do you think success looks like in math?

- How do you learn math best?

- Describe a time you did something great in math class.

- What is your goal in math this year, and how can I help you reach it?

Small group discussions, morning meetings, and even individual interviews are all great ways to “take the temperature” of students’ math identities. Some students may prefer to put their thoughts in words. Others may wish to complete a survey, or even a visual representation or drawing of their math experiences. You might also consider having students write a letter to math, as if math were a person.

We think you’ll be surprised by what students share with you. Understanding the emotional math baggage students bring with them can help teachers create a new philosophy for their math classrooms.

Once you and your students have reflected on your math identities, develop a vision and key understandings for your math classroom. This philosophy around math might include statements like, “In this math classroom, we view mistakes as opportunities,” or, “We believe that there is no such thing as a ‘math person’—everyone can do math.” Allow your students to help create norms that promote risk taking, encourage mathematical discourse, and provide encouragement through productive struggle. Place these norms prominently in your classroom.

Math in a universally designed classroom provides students with multiple ways to show us what they know and engage with the content.

Building New Classroom Practices

Developing a classroom culture of students with positive math identities requires not just a philosophy, but strong instructional practices. Universal Design for Learning, or UDL, is a powerful framework to make math more accessible for all students in your classroom. UDL can be defined as a framework for inclusive instruction that accounts for individual variability through intentional design that reduces predictable barriers to learning. It provides multiple ways for students to access information, express their knowledge, and engage with the content. Let’s break this definition down as it relates to developing positive math identities.

As a framework for inclusive instruction, our goal is for all students to be developing positive dispositions toward math and to identify as doers of math. If we believe this, we must reject popular practices of sorting, labeling, and tracking students. Moving some students to separate classrooms or relegating them to low-level courses is in direct contradiction to inclusive instruction. In the first few days or weeks, you may receive information about the results of your students’ learning from the previous year. Maybe you are reviewing data, looking at last year’s report cards, or even chatting in the hallway with last year’s teachers. When you are reviewing this information, look past the sorting and labeling and discover the things your students can do. It is the strengths of your students that will create leverage points for future learning in math. If you don’t believe in them, then who will?

“But how,” one might wonder, “can we reach the wide range of learners in our math classrooms with so many different needs?” The UDL framework proactively and strategically accounts for learner variability through intentional design and the reduction of predictable barriers. Intentional design means that rather than adding accommodations and modifications to a lesson after the fact, we plan from the start. Instead of teaching to the mythical average student, we consider the student in our class who has the most challenges, as well as the student who needs the most challenge in the form of extension. When we identify entry points for learners at these two ends of the spectrum, all our students are more likely to “find a way in” to the curriculum.

Math instruction in a universally designed classroom provides students with multiple ways to take in information, show us what they know, and engage with the content. Some students will benefit from visual supports, others may excel through building, and others may be fine with a traditional paper and pencil method of solving. Considering the variability in students and changing up instruction to support those needs allows us to recognize that if all students learn differently, we can’t teach them all in the same way.

Everyone Can Do Math

Many of us are guilty of deeming students, and even ourselves, as “math people” or “not math people.” Our intentions are likely well-meaning. Maybe we were providing comfort when a student wasn’t feeling successful. Maybe it was easier to chalk up our own difficulties with the topic to a fixed attribute outside of our control. Whatever the case, we must abandon those beliefs and statements. The year ahead is full of possibilities. If we adopt a universally designed approach to developing classroom philosophies and practices, we can support students in thriving as successful learners with healthy math identities. Everyone can do math!

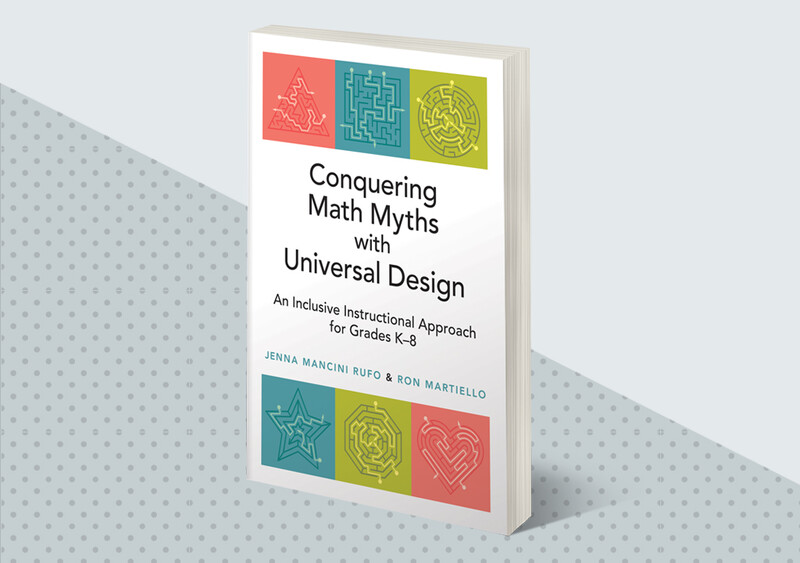

Conquering Math Myths with Universal Design

Rufo and Martiello dispel math myths, creating more inclusive and accessible math instruction that empowers students.

Ron Martiello is a learning coach in Montgomery County, PA. He has served as a 1st grade teacher, an elementary assistant principal, and elementary principal.

In 2018, Ron became a learning coach to support teachers in the areas of technology and math. You can learn more about Ron by following him on social media.