We put a lot of information into our students’ heads. But are they retaining it? Pooja Agarwal—a cognitive scientist, founder of RetrievalPractice.org, and coauthor of Powerful Teaching: Unleash the Science of Learning (Jossey-Bass, 2019)—says retrieval practice, which can be done in as a little as one minute, makes learning stick. A recent literature review confirms it.

Can you briefly describe what retrieval practice is for educators unfamiliar with your work?

One way that I sometimes frame retrieval practice is to ask, “Do you remember what you had for breakfast yesterday?” When you pause to think about the answer, you’re experiencing the same kind of internal feeling as retrieval practice—Wait, what did I eat for breakfast yesterday?

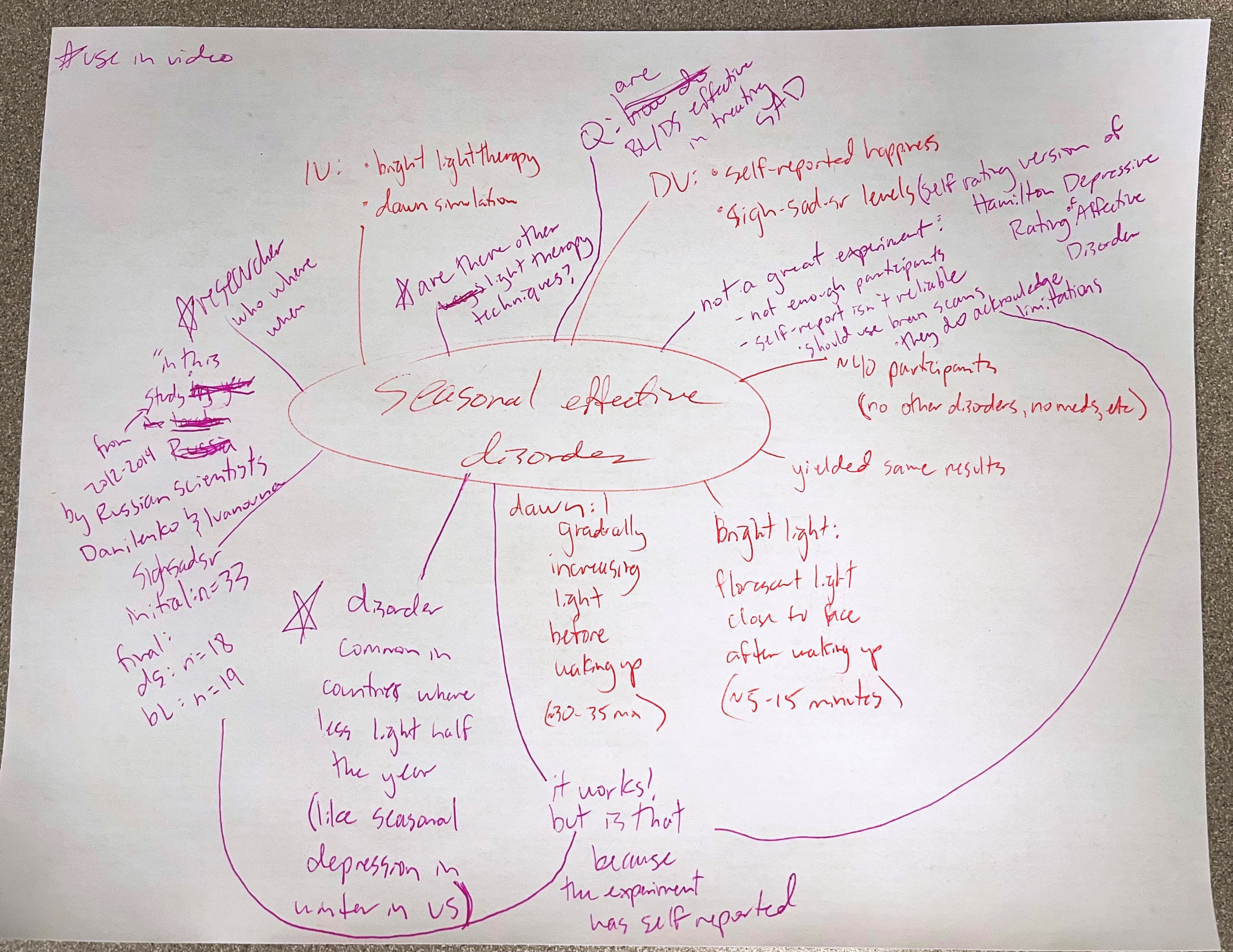

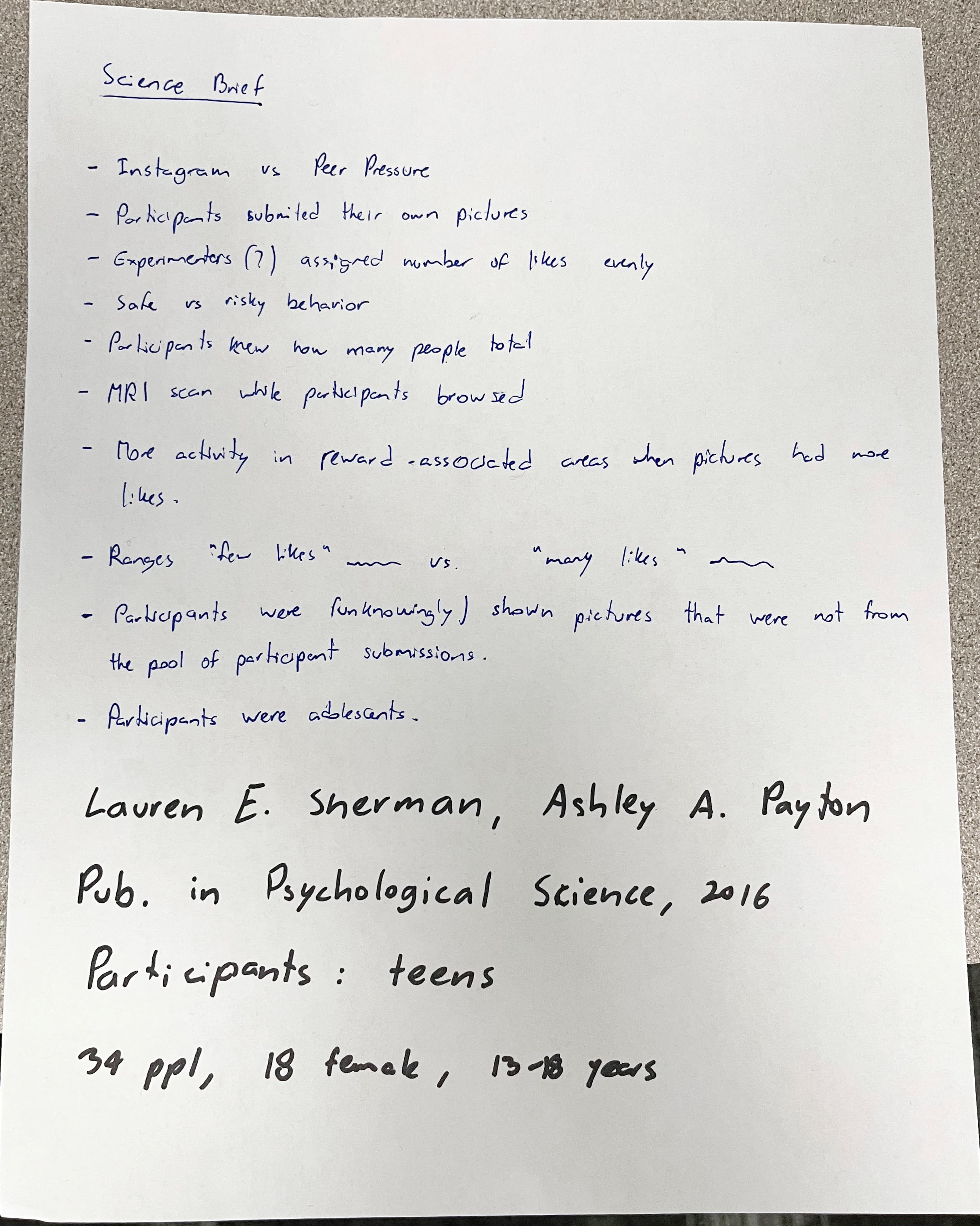

Last week, in the middle of class—I teach psychology at the Berklee College of Music in Boston—I handed out blank sheets of paper to my students and asked them to write down everything they could remember about the scientific article they’d each been studying for the past few weeks (see fig. 1). I gave them no other prompt, other than reassuring them that this wasn’t for a grade. That feeling of mentally traveling backwards—with a “brain dump,” in this case—is similar to thinking about what you had for breakfast yesterday.

Retrieval practice—the act of recalling previously learned information—is engaging students to get information out of their heads. What I could have done, and what a lot of us do as teachers is, midway through the semester, say: “Here’s a list of all the topics we covered, here are some of the key points I want you to know, and now let me give you a mid-term exam.” When teachers review concepts, we are getting information “into” students’ heads. Instead, we know from 100 years of research that a powerful part of learning is getting information “out” of their heads with retrieval practice. For example, instead of just giving students a review sheet or a list of topics, simply asking them, “What are the topics that you remember?” engages that process in our cognition that helps strengthen that memory.

Teaching and learning are complex processes. At the same time, here’s a simple key to both: remembering. We want our students to remember what they learn. On the first day of the semester with my college students, I start by sharing that I want them to remember what they learn, beyond the semester, beyond the school year, and for years to come. Our students forget, we reteach, they forget, and we reteach. With retrieval practice, we can stop this frustrating cycle of short-term learning. Retrieval practice is one of the simplest, research-based strategies we can use to transform their long-term learning.

Do you collect those sheets of paper?

No. I don’t collect them and I don’t grade them at all. This emphasizes that retrieval practice is a learning strategy—not an assessment strategy—and also that students can keep their brain dumps as notes or “artifacts” of what they’ve learned.

Figure 1: Examples of Student "Brain Dumps"

Source: Pooja Agarwal

Your team worked closely with a classroom teacher for several years to measure whether retrieval practice made a difference in student learning. What did you find?

We first started our research with Patrice Bain, a 6th grade social studies teacher at the time and the co-author of our book, Powerful Teaching. I was in her classroom eight hours a day, five days a week for the entire fall of 2006—just seeing how she taught, how she already used retrieval practice, and how we could set up the research without disrupting her lessons. No one in our field had ever conducted this kind of research on retrieval practice in real classrooms.

One of the most exciting things that my colleagues at Washington University in St. Louis and I found was that we could apply this laboratory-based concept in Patrice’s classroom without an overhaul. We didn’t change her materials, her textbooks, or her style of teaching. Patrice and I simply added in a few quick clicker quizzes (this was before Kahoot and common tech tools today), a few brain dumps, and a few additional questions on unit exams to measure long-term learning. It was validating to know that we could make retrieval practice work logistically in the real world, even when there were snow days, school assemblies, and students out sick.

As Patrice likes to put it: “With retrieval practice, students know what they know and they know what they don’t know.” This highlights an additional benefit of retrieval practice: improved metacognition because students reflect on their own learning.

From 2006–2014, we collected data in Patrice’s classroom and in multiple grade levels and subject areas in her public school district, ranging from 6th grade to 12th grade science, language arts, and history classrooms. The data we collected, from thousands of students over almost a decade, demonstrated statistically significant benefits even nine months later. In addition to improving long-term learning, we have found over time that retrieval practice helps students remember higher-order concepts—not just recall facts—and it reduces student anxiety for unit tests.

With consistent use of retrieval practice, we raised students’ grades from a C to an A level. Students found that they could remember more. They loved engaging in brain dumps, and they felt more comfortable and confident.

What does it look like in classrooms? How often should teachers use retrieval practice strategies?

As much as we might want a “perfect recipe” for retrieval practice, recent research suggests that there’s no one optimal approach to implementing retrieval practice. I recently published a literature review on retrieval practice—my colleagues and I looked at 50 experiments in classroom settings ranging from elementary school to medical school—and we wrote about how everything kind of just works. Regardless of timing, frequency, question format (multiple-choice or short answer), grade level, and content area, the majority of experiments revealed medium to large effect sizes, indicating that retrieval practice improves learning consistently in real world classrooms.

With consistent use of retrieval practice, we raised students’ grades from a C to an A level.

Pooja Agarwal

Instead of a perfect recipe, here’s my advice: You do you as a teacher. Be creative. If what works in your class is a brain dump every two weeks, and you can keep track of that and build it into your lesson plans, go for it. I like that it can be spontaneous and still beneficial for learning. Or it can be part of a classroom routine, like an entry ticket. It helps to have research-based strategies on hand—like the brain dump and “two things” (at any point during a lesson, have students write down two things about a specific prompt, e.g., What are two takeaways from today?)—but then how you implement them is totally flexible, open, and fair game.

What would you ask on an entry ticket?

One of the easiest questions to ask is, “What do you remember from our last class?” You can have students do the entry ticket on paper or use something like Google Slides so they can look at each other’s responses. And then move on. It doesn’t have to be a whole-class discussion. I have the slides for formative assessment if I want to go back later and see if students missed a concept, but I emphasize that this retrieval practice is for them–to boost their own long-term learning. Just like brain dumps, we don’t have to grade students’ entry tickets. We don’t have to grade retrieval practice at all. Entry tickets are an engaging opportunity to get students warmed up without reviewing what you taught during the last class. Students can retrieve, pull this information out, strengthen their learning, and be ready for more learning.

How do you know, in the context of retrieval practice, if a student is struggling productively?

Struggle is a good thing: Easy learning is like easy forgetting. When we feel like learning is coming easily to us, we remember it in the short-term but not the long-term. What people remember in the long-term is what they struggle with. The phrase we use in the scientific literature is a “desirable difficulty.” Even if a student is struggling, we have to trust ourselves as teachers and encourage that student to just stick with the struggle.

Why do you think every teacher isn’t already using this technique in their classrooms?

For a few reasons. Part of it is that we’re trained in a literal sense to teach how we were taught. We start class by saying, “Here’s what we did last time, now let’s move on.” So, I think it’s a habit.

Some of it is a lack of awareness of the research. Retrieval practice is not a fad. It’s not just based on anecdote.

And then a lot of the hesitation comes from the implementation. OK, yeah, you say it takes one minute or less but this whole “retrieve-pair-share” strategy sounds like it’s going to take 10 minutes. I’m not going to do it, so let me go back to my old habits.

Believe me, I get it. If someone told me, Pooja, you should exercise five days a week, I’m not going to do that! I know it’s good for me, I know research says I should do it, but I’m not going to do it. So how do I get myself to actually do it? Well, I keep my yoga mat out, I find YouTube videos that are literally five minutes long, and then when I feel more comfortable, I tend to do more.

Retrieval practice isn’t throwing the baby out with the bathwater. These strategies can take one minute or less, and that’s not an empty promise.

More on Retrieval Practice by Pooja Agarwal

Like practicing an instrument or a language, durable learning takes place when students use what they know, writes Agarwal in the March 2020 issue of Educational Leadership. Pulling information from memory is also key to long-term transfer.