I love a good metaphor, but the one about self-care being an oxygen mask just doesn’t make sense. Let’s start with the obvious: Oxygen masks are important tools to help us keep breathing in an emergency. Self-care is about taking steps to support the best versions of ourselves—it does not require us to be in crisis or in need of emergency support.

Yet, as teachers, why do we often rationalize taking care of ourselves in this way? Perhaps our tendency to run ourselves down to such alarming levels relates to the high rates of teacher burnout. We need to value ourselves as whole individuals playing many roles that require our hearts, minds, and bodies to be in strong working condition.

I think we can do better—not only in terms of metaphors, but in terms of valuing self-care. Let’s get away from that dire oxygen mask situation and consider what makes travel enjoyable—an in-flight meal, a tray table for your book or laptop, a reclining seat. We could equate these to having healthy snacks and lunch as part of the workday, setting up an organized work area, and making time for sleep each night.

Let’s take this metaphor further. What if we could enjoy first-class accommodations through self-care? What if teachers and students could enjoy a premium experience with a menu of choices for when, what, and how to approach learning?

Teacher Self-Care

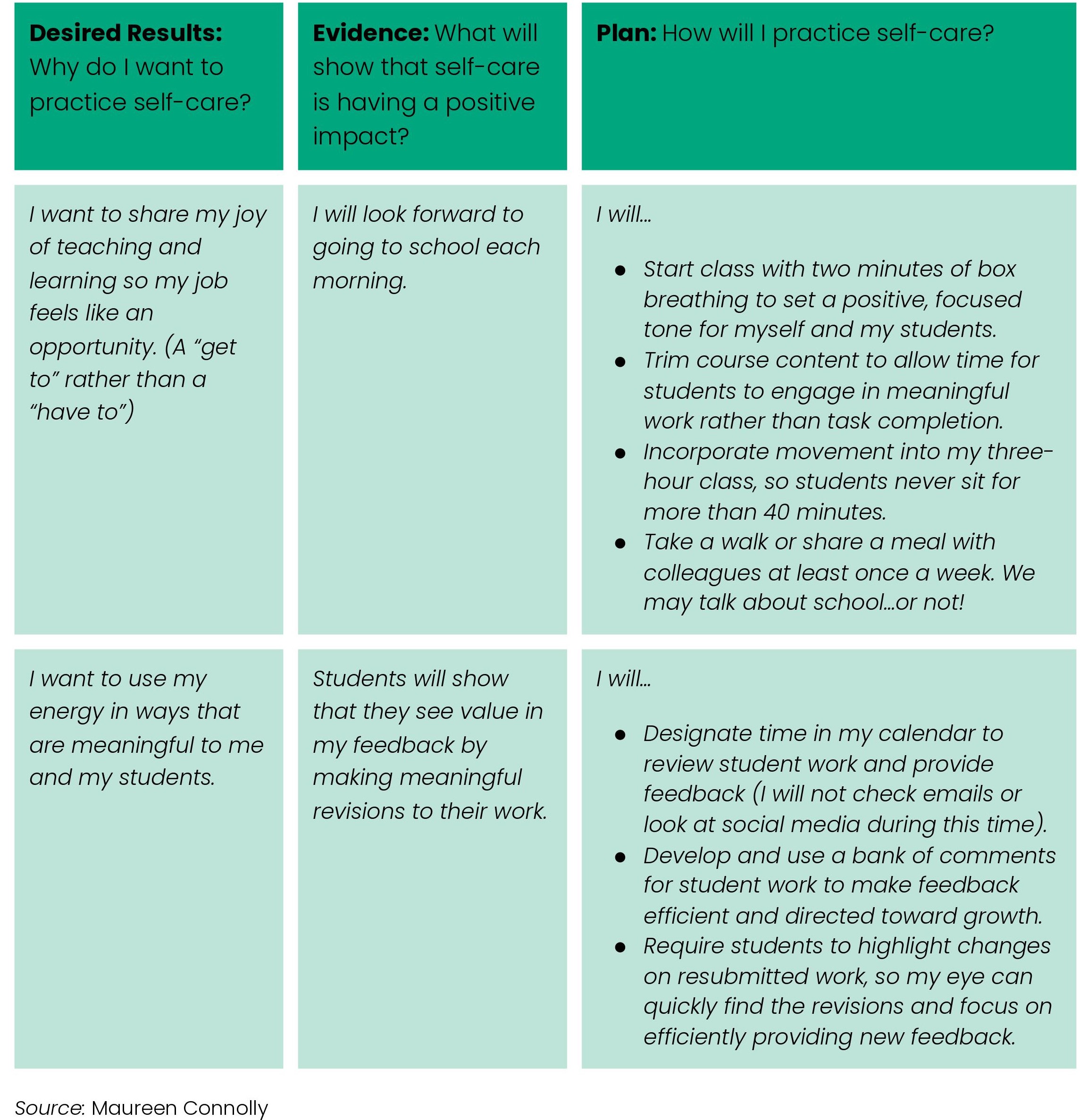

A premium experience sounds good, but how do we create this? How do we think about self-care in a truly teacher-specific way? One way is to use Understanding by Design (UBD). Teachers can ask themselves three key questions about teacher self-care that align with the three stages of UBD:

- Desired Results: Why do I want to practice self-care?

- Evidence: What will show that self-care is having a positive impact on me?

- Plan: How will I practice self-care?

When we think through our own experiences and needs from year-to-year, month-to-month, or week-to-week, we can plan a course of action that is meaningful and measurable. See my example:

As teachers, we know the value of UBD in keeping us focused on our desired results while still allowing for flexibility. If an approach needs tweaking, we differentiate to meet our students’ needs. Let’s commit to doing the same for ourselves. For example, my plan to balance time during the week to avoid grading over the weekend may not always work out for me. I can adapt it to say that even if I bring work home over the weekend, I will have more memories relaxing than grading by the time I reach Sunday night.

Speaking of fun and relaxing, let’s return to the idea of a first-class experience.

First Class in the Classroom

When first class was introduced, it really just meant a large reclining seat. Over time, it evolved to include seats that transform into beds, privacy dividers, individual screens, and even suites that have lounges and showers. The airlines adapted and pushed their thinking to match the desires of passengers.

We need to value ourselves as whole individuals playing many roles that require our hearts, minds, and bodies to be in strong working condition.

What if we as educators could take risks and make structural changes to make more room for comfort and for stretching students’ minds in new ways? Below are three ways to engage in the kind of innovative thinking and meaningful action that will dramatically improve teaching and learning experiences.

1. Zero-based thinking. Rather than thinking about changing what your classroom or school looks like now, start at zero. Imagine you are building your school from the ground up. What would you create? Would you even have classrooms? By engaging in zero-based thinking, you can push yourself to envision possibilities that may seem impossible. From that thinking, you can apply elements that will work in the here and now.

My favorite example of zero-based thinking comes from the Marymount School in Rome. I was fortunate enough to work with student teachers at the school, and when I asked about teacher self-care, the principal shared that one of the best things they had done was create a doggy daycare at the school. School faculty and staff bring their dogs to work with them and can visit them during the day. This removes the stress of scheduling a dog walker, and it reduces the guilt of leaving a dog home alone while at work. Plus, talking about pets is a great way to connect with students.

2. Genius Hour. This innovative, creative, and personal time isn’t just for students. You can engage in Genius Hour right alongside your learners. The concept of Genius Hour has been promoted in the corporate world, such as at Google, where employees are encouraged to use 20 percent of their time focusing on projects sparked by their own passion and curiosity. The intent is to boost morale and transfer that positive energy into work projects. We often say we want our students to be lifelong learners. What about us? What are we passionate about learning? How can we model that passion and commitment for our students?

My brother was an elementary school principal for many years. When he was hiring new teachers, his favorite interview question was, “What would your Genius Hour project be?” Many struggled to respond at first. Then they would start their answer with some variation of the phrase, “This is going to sound crazy, but…” They would jump into a variety of topics from learning calligraphy to studying the stories behind hockey players’ jersey numbers. We want schools to be places where we can get excited about learning alongside our students.

3. Praise risks before they are taken, not just after they work out. Risk doesn’t guarantee success. That’s why taking a risk is risky! We need to praise others and ourselves for risks before, during, and after they are taken, not only when they work out.

As a teacher educator, I encourage my students to take risks. I want them to get creative in their approaches and lead memorable experiences for their students. Of course, I also want them to be safe and professional, but I believe they can do so while going beyond what they have experienced as students. By praising risk before it is taken, we reduce the stress inherent in the risk. For my students who are pre-service teachers, for example, this may look like a non-sports guy developing a basketball-based review game because he knows his students love basketball. Students (and teachers) who have dared to take risks have found success (even when the results weren’t great) because they pushed past their concerns about taking a chance.

As teachers, we may not be buying first-class tickets when we travel, but we can do our best to create first-class experiences for ourselves and our students. I hope that we will all engage in the impactful moves shared here. Just as important is to model these strategies and encourage our students to take similar action, thus getting us all into first class.