Today’s students are global media consumers with access to a constant stream of visual information from internet content, social media, videos and television, AI-generated images, and other multimedia sources. Despite the abundance of this imagery, “visual literacy is a learned skill, not an intuitive one,” write Douglas Fisher and Nancy Frey in their April EL column. How, then, can educators be intentional in how they teach students to make meaning of the images they encounter?

Visual literacy, according to Fisher and Frey, “describes the skills and competencies needed to think critically through photographs, illustrations, and moving images.” When students practice visual literacy, they are expanding their critical thinking skills by evaluating and interpreting nonlinguistic information. Simple but effective frameworks can help educators approach the visual analysis process with intentional skill-building in mind. By thoughtfully selecting and strategically unpacking complex images, educators can help students make the shift from “information consumption” to “deeper thinking and discussion” when evaluating an image.

For example, Fisher and Frey describe a quadrant approach to help students break images into four smaller parts, observe the quadrants one at a time, and home in on details that may otherwise get lost in the bigger picture. Much like close reading a language-based text, quadrants help students notice details and recognize more nuanced aspects of an image.

Another framework relies on a series of questions, which educators can cycle through and repeat as students deepen their analysis. By asking, “What's going on in this picture?” “What do you see that makes you say that?” and “What more can you find?” educators encourage students to move beyond a first glance and approach visuals with an in-depth critical lens.

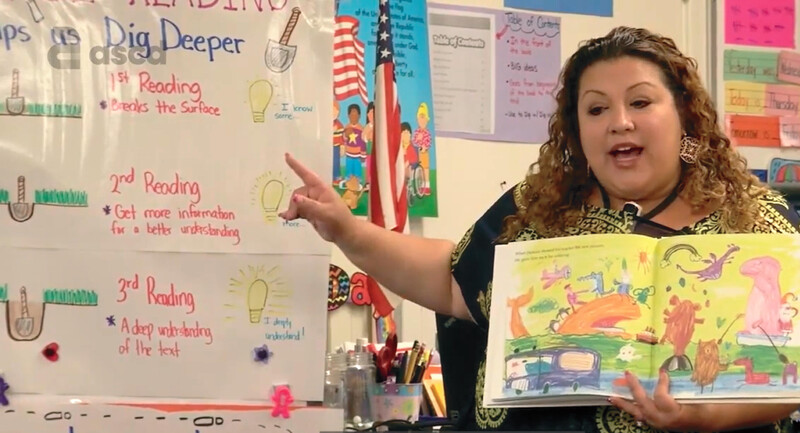

In the video that accompanies Fisher and Frey’s column, kindergarten teacher Lisa Forehand walks her students through a close-reading protocol to help them make detailed observations about an image, locate visual evidence to support their observations, and repeat this process to deepen their understanding of the image’s meaning.

Teaching Strategies

Teaching StrategiesShow & Tell April 2023 / Teaching with Visuals

3 years ago

In The Day the Crayons Quit by Drew Daywalt (Philomel Books, 2013), Duncan, the protagonist, draws a picture using all his crayons. The crayons have different wants and needs, Forehand tells students. For example, the red crayon says it’s overused and needs a rest. By the end of the story, Duncan creates a picture that reflects how he has listened to each crayon and has addressed their problems.

Forehand begins by asking students to review each crayon’s problem, helping the kindergarteners recall what they already know. To build onto their knowledge, Forehand then outlines what it means to “dig deeper” into a nonlinguistic text. She uses a picture of a shovel as a visual cue to remind students that close reading an image is a process: “The first time we read a text,” she says, “we know a little. The second time we read it, we know more. The third time . . . we completely understand.”

Students model the steps of this process by first making observations about colors, shapes, sizes, and other visual details of Duncan’s image. They notice, for example, a large orange whale and some small grey penguins in the picture. They then provide evidence—marked by the word “because”—to connect their initial observations to their interpretations of the crayon’s feelings. Students are eager to share that the grey crayon, who was tired of only coloring large creatures like whales, is now happy because it got to color the small penguins.

Not only does Forehand break visual analysis into smaller steps, helping students distinguish among skills like observation, interpretation, and evidence-gathering, but she also has students practice critical thinking in different instructional settings: in small-group conversations, whole-class discussions, and individually. Once students have discussed their ideas aloud, Forehand has each of them pretend to be Duncan by writing a letter to one of the crayons explaining how they solved that crayon’s problem. One student, demonstrating the depth and complexity of her understanding, writes: “Dear Pink, I solved your problem by coloring pink dinosaurs. I would have loved to make more pink cowboys and monsters, but I had to solve other crayons’ problems, too.”

Forehand is preparing these kindergarteners to understand the value of visual literacy and its step-by-step implementation. By breaking the visual analysis process into intentional steps, her students are able to make detailed observations about the image and support their interpretations with visual evidence.

“The images selected in textbooks and other teaching materials can offer a broader lens for understanding the academic, social, and emotional concepts we teach each day,” write Fisher and Frey. “With the right implementation, visual literacy instruction can elevate critical thinking and discussion in your classroom.”