In the fall of 2003, I stepped out of a history seminar at California State University into dense heat, billowy black smoke, and an ominous red sky. When I arrived at my apartment nearby, my roommate was watching the news, where the word wildfire peppered the tide of reporting rushing from the screen. Before long, sirens sounded outside our windows. Our worried families in other states had gotten word of the fires and frantically called us about evacuating. Yet we waited. We saw the flashing scroll at the bottom of the screen commanding us to evacuate as soon as possible. But, even as the heat surrounded us, we were inexplicably frozen in place.

Soon, we learned that our friends in an apartment down the street had evacuated. Knowing our friends left is what sprung us into action. My roommate found a place near the coast for us to go. The sirens raged as we threw our bags together, loaded up the car, and watched the burning mountains through our rearview mirror. Other than a couple of nights worth of clothes, I grabbed a photo album, my computer, and my cat.

That particular wildfire in San Bernardino was called by officials “The California Fire Siege of 2003.” It burned for more than a week and took 91,000 acres and six lives in its wake. My roommate and I were among 70,000 people who eventually evacuated.

Decades later and on the other side of the world, this phenomenon—a kind of delayed reaction to disaster—drove Ken Strahan, an Australian researcher, to try to better understand what causes people to freeze in moments of crisis. For a long time, authorities in Australia operated under the assumption that people waited to evacuate in the face of environmental danger for only one reason—fear. Policies were built around this assumption. Committees, programs, resources, and practices addressing people’s fear during times of crisis were put into place. Money, time, energy, and human capital were spent toward these efforts.

But Strahan's research (outlined in this video) illuminated something that no one had yet considered: Humans are more complicated than this simple narrative of fear. Strahan spoke with 457 people who had recently experienced bushfire evacuation, and he learned that there were many reasons people stalled during these moments, none of which could be attributed to fear alone. For example, some people neglected to evacuate quickly because they had dependents to care for, so they needed to create a plan for supporting them. Others were “community guided” (as my roommate and I had been), meaning they waited for those around them to take action, sometimes going in caravans together. Strahan calls these categories of evacuation styles archetypes.

These archetypes have been a game-changer for how jurisdictions effectively support safe evacuations during a bushfire. Rather than build entire systems around a singular narrative of human behavior rooted in assumption, the archetypes have provided insight into a more nuanced understanding of human nature. Now bushfire evacuation programs, resources, and efforts in Australia are being redesigned toward helping people develop their own unique escape plans, rather than commanding top-down actions founded on a misunderstanding of people’s needs.

A More Human Approach to Change

Does all this sound familiar? The education profession is riddled with assumptions about the people within its system. It’s easy to understand why we rely on assumptions rather than accuracy within a complex human-based system that is constantly changing. It would be virtually impossible to make systematic decisions based on each individual’s tendencies, even at the hyper-local level. Yet it is still possible to design systems that extend beyond broad assumptions and align more closely with actual human behavior if we follow Strahan’s example and operate archetypally.

Knowing our own patterns of behavior provides a level of self-awareness that empowers us to take more ownership of our fates during moments of change.

Around the world, researchers are now working to better understand everything from neighborhood health, natural landscapes, organizational change, and even violent extremism through the lens of archetypes. This archetypal approach effectively inserts humanity into complex problems when we would otherwise be tempted to take shortcuts for the sake of efficiency. These seemingly easier shortcuts leave us spinning our wheels and reacting to problems rather than responding.

We are at a critical juncture in education, facing a slew of pressing and unprecedented challenges—such as educator shortages, mental health crises, exacerbated inequities, and political battlegrounds. Why not take the opportunity to address these issues with a more human, individuated approach, rather than relying on outdated assumptions that may no longer apply to contemporary concerns? Just as government authorities are implementing new policies at the systems level to support safer evacuation through an archetypal approach, might an understanding of archetypes also help us glean better solutions during changing times in education too?

The archetypal approach to addressing crises or any kind of change benefits not only systems and leaders, but individuals as well. Knowing our own patterns of behavior provides a level of self-awareness that empowers us to take more ownership of our own fates during moments of change. Had my roommate and I known that we were “community guided,” as Strahan calls it, we may have cut through the noise quickly and simply called our friends to find out what their plan was, rather than waiting for them to volunteer that information. As these complex changes confront the education system, it is critical not only for leaders in traditional positions of power to understand change archetypes, but also for every individual to better understand how they can best navigate these changes as well.

Beginning in 2020, as we were all forced to respond to the growing pandemic, I engaged in an informal research project about the change process. Following Strahan’s footsteps, I conversed with hundreds of educators and leaders across the globe and sought patterns within those conversations. I noticed trends emerging as to how people responded to abrupt change, how they addressed the various problems that arose, and how they envisioned innovative solutions. I distilled the patterns from these conversations into eight “change archetypes” that I believe could provide sustainable approaches to addressing some of the sticky problems we now face in education.

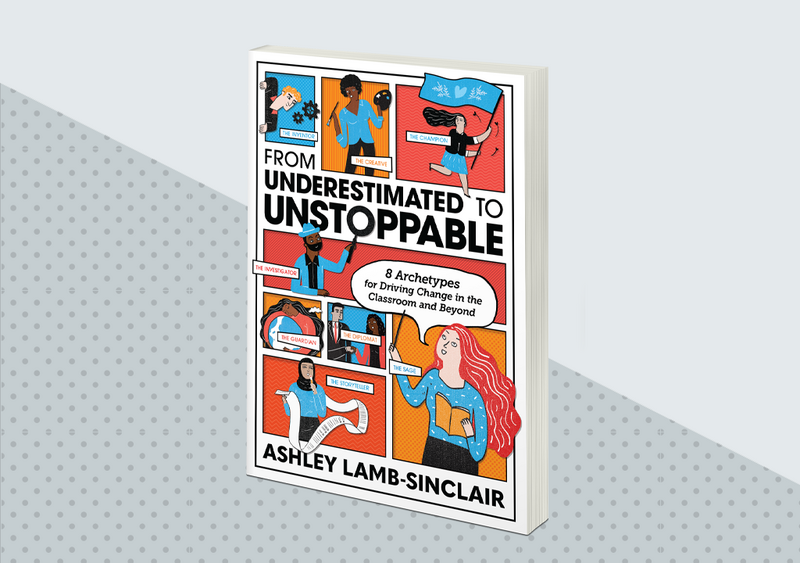

These change archetypes, featured in my book From Underestimated to Unstoppable: 8 Archetypes for Driving Change in the Classroom and Beyond, are:

- Diplomats who build relationships and value fairness and integrity.

- Champions who are passionate about a cause and advocate for people and ideals.

- Creatives who approach things through novelty and ingenuity.

- Storytellers who are thoughtful, attentive to details, and clear communicators.

- Inventors who are forward thinkers who operate through free experimentation.

- Sages who are perceptive, insightful, and persuasive.

- Investigators who have an analytical curiosity, ask probing questions, and conduct thorough research.

- Guardians who have compassion for and are drawn to nurture and protect others.

A School of “Diplomats”

Consider my classroom educator friend and colleague, Kip. Kip is the main inspiration for the change archetype I call the “Diplomat.” I’ve known Kip for nearly a decade and I have seen his work over time, especially during times of change. When #edchat first gained traction on Twitter, Kip taught himself how to be central to the conversations that interested him. He engaged with a global network of practitioners and brought new ideas and knowledge back to his colleagues. When he felt the itch to try a different teaching environment, he tapped into the relationships he had developed over his career to find a new role in a new school. Within these moments, Kip’s unique approach as a Diplomat—a drive to connect with others—has guided him through change.

So, what if there were a school building of Kips—Diplomats who rely on relationships when things get tough? If low morale plagued this particular school, a well-meaning school leader might offer an afternoon off rather than proceed with a scheduled faculty meeting or set up a quiet retreat space in the teachers’ lounge to support staff well-being. These are great ideas, at least on the surface, founded in compassion.

Whatever the combination, solutions to pressing problems can be more closely tailored to the needs of real people when we account for archetypes.

But if this faculty is composed of a large population of people who thrive on connection and relationships, taking away time to connect or creating isolated spaces will not only not work, but it may actually exacerbate the problem. As well-meaning as these ideas may appear to be, they are rooted in assumptions about what might make educators “feel better” in the same way the Australian authorities assumed people weren’t evacuating in time because they were afraid. Assumptions can trick us, but unless solutions for complex human-based problems are created through a human lens, these “solutions” often become a waste of time, energy, and resources. And they do not actually solve the problem they are meant to solve, no matter how well-meaning.

With a “Diplomat-heavy” staff, this hypothetical school leader would be better off redesigning faculty meetings to be more organic and conversational, rather than further isolating the staff from one another. But if the staff were composed of an equal split of Diplomats and Creatives—individuals who thrive on generating ideas—the leader might provide a weekly collaborative brainstorming session rather than a traditional faculty meeting, thereby addressing the connection needs of the Diplomats and the generative needs of the Creatives.

Whatever the combination, solutions to pressing problems can be more closely tailored to the needs of real people when we account for archetypes. And when the educators within a school understand their own needs as Diplomats or Creatives or Sages and so on, they should be empowered to embody them and contribute to solution-building as well. In this way, problems plaguing the school can become collaborative opportunities to lead change collectively, rather than a top-down rat race of wasted energy.

Answer the Call

We are all being asked to embrace new changes today, whatever our role; so, when the metaphorical wildfire rages toward our front door, how will we respond? Just as Ken Strahan has learned, the answer to that question matters more than we might suspect. Understanding archetypes—as many innovative thinkers across industries are discovering—can help leaders support a more human-based approach to solving big sticky problems because they offer a workable middle ground between solutions based on assumptions and solutions based on individual opinions.

Without a middle ground, it will be very difficult to address the problems we are facing and move collectively from impending disaster to effective disruption. We do not need to freeze in fear, repeat ineffective behaviors, or operate from assumptions. We do not have to wait for a call from elsewhere to do what is best for ourselves, for each other, and for the young people in our care. We can make that call ourselves, right now.

Which change archetype are you?

From Underestimated to Unstoppable: 8 Archetypes for Driving Change in the Classroom and Beyond

Don't let the change story continue without its most vital character—you! Dive into how to lead change through an archetypal approach.