In New York City, two black children and one Hispanic child are attacked (in separate incidents) and have their faces stained with white paint by Caucasian teens. In Berkeley, California, several randomly chosen white students are beaten by black classmates after racist leaflets are distributed on a high school campus. Dubuque, Iowa, is rocked when the town's efforts to attract more black residents set off clashes between white and black students and a series of cross burnings.

Such incidents, culled from a host of media accounts of racial conflicts over the past two years, do not necessarily suggest that race relations among youth are at a crisis point. Still, experts on race relations say that American society—and schools—must make considerable strides to stem racial conflict and encourage more harmony among our increasingly diverse youth.

More children from diverse racial, ethnic, and cultural backgrounds are attending schools, and some students and school staff aren't comfortable with that fact. Schools are experiencing “an intensification” of racial and ethnic disputes between students, says Joan First, executive director of the National Coalition of Advocates for Students. “To a large degree,” she adds, “schools aren't very well prepared to deal with this.”

Efforts to desegregate schools over the past three decades have also resulted in more students' having to become more accustomed to classmates of diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. This familiarity has helped to bring about many positive outcomes, but it also partially explains what some experts believe is an alarming level of racial conflict among our youth.

“Desegregation brings the opportunity for harmony, but there's the potential for more conflict unless there are interventions” to improve understanding and tolerance among students, says James Banks, director of the Center for Multicultural Education at the University of Washington. “Schools are often more diverse than the places where [students] live, so they can become a flash point,” agrees Cynthia Coburn of the National Coalition of Advocates for Students (NCAS).

More Interracial Friendships

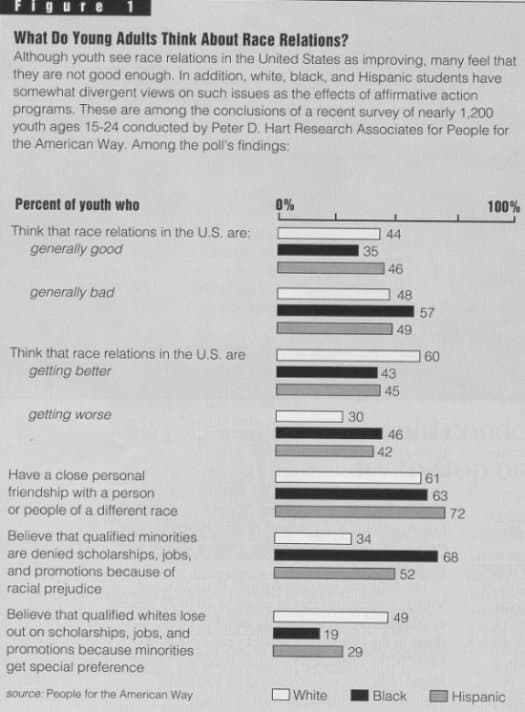

On the bright side, students today are very likely to have friends in different racial and ethnic groups. A survey conducted for People for the American Way (see fig. 1) found that more than 70 percent of 15- to 24-year-olds reported having a “close personal friendship” with a young person of another race. Moreover, those polled saw themselves as much more comfortable than their parents in dealing with individuals of another race. This was consistent with their view that race relations are generally improving, albeit slowly, according to a report based on the poll data. “Most young Americans see their generation as part of a slow march toward progress on racial problems,” the report found.

Figure 1. What Do Young Adults Think About Race Relations?

At the same time, there are worrisome signs that racial discord is an accepted fact of life for some students. A Harris poll conducted in 1990, for example, found that more high school students said they would join in or silently support a racial confrontation than said they would condemn or try to stop one.

Today's young people are the victims—and sometimes the instigators—of the same brand of racial hatred and conflict that has plagued America for generations. Although national statistics on racial conflict and violence among school-age children are not compiled, there is evidence that the problem, if not growing, persists at unacceptably high levels. As the examples above suggest, racial discord takes many forms in schools, including racial graffiti, slurs, and harassment, and racially motivated fighting or unprovoked attacks.

For example, NCAS recently tracked newspaper stories on incidents of racial and ethnic conflict in schools for a two-month period on a nationwide basis. During the study period, between Dec. 15, 1991 and Feb. 15, 1992, nearly 120 incidents were reported across 25 different states. Klanwatch, a project of the Southern Poverty Law Center, documented more than 270 incidents of hate crimes in schools and colleges during 1992, more than one-half of them perpetrated by teenagers. Such tabulations are likely to be quite low, however, since newspapers document only a fraction of all racial incidents, and schools and the victims themselves frequently don't report them. Several years ago, the Los Angeles County school district reported more than 2,200 hate crimes during a single school year in its region.

The National Institute Against Prejudice and Violence estimates that as many as 20 to 25 percent of students are victimized by racial or ethnic incidents in the course of a school year, says Howard Ehrlich, the institute's research director. “Every single indicator we have suggests that ethnoviolence incidents are at least steady, if not increasing,” he says.

Overt racism and prejudice is no doubt a factor in some of the racial and ethnic conflict plaguing school campuses. Unprovoked beatings and racial slurs and harassment, for example, leave little doubt as to the offenders' intentions.

Misunderstandings Common

At other times, problems arise when lack of awareness of the norms and practices of other races or cultural groups leads to misunderstandings, hurt feelings, or worse. William Kreidler, an expert on conflict resolution for Educators for Social Responsibility, describes an incident he witnessed at a middle school. A friendship had blossomed between a young Cambodian student and an African-American peer. One day, however, the African-American student shouted across the playground to her friend. The Asian student, feeling chastened and humiliated at being loudly singled out, looked away. The African-American student, in turn, felt hurt and embarrassed by her new friend's reaction. In such ways, students' lack of understanding of other cultures contributes to tension and, sometimes, conflict among peers.

Moreover, when conflicts with racial dimensions do arise, students “often don't have the skills,” to resolve them peacefully, says Sara Bullard, editor of the Southern Poverty Law Center's Teaching Tolerance. “They are not taught the skills of cooperation and conflict resolution early enough or broadly enough” to prevent conflicts from escalating. Even incidents that don't begin as a racial conflict sometimes become one as the problem escalates, experts say. For example, it is not uncommon for a fight or argument between two students of different races or ethnic backgrounds to escalate into a series of insults, epithets, and physical fights between different groups of students, sometimes over several weeks or longer.

When a conflict or incident occurs, deeply held racially-charged beliefs may come out in the open. For example, a high school in suburban Virginia was plagued by fights between black and Hispanic students spurred by an off-campus stabbing. A Washington Post reporter who later interviewed students at the school discovered longstanding strong feelings about racial issues that had simmered beneath the surface. For example, some students felt that school officials monitored minority students more closely and punished them more severely than they did white students. Black and Hispanic students accused each other of being insular and cliquish.

How Schools Can Help

Although schools cannot solve the problems of racial discord, they can do much to improve relations and reduce conflict among students of various races and ethnic backgrounds.

A good start is to ensure that the school's mission statement, norms, and policies support the value of diversity and contain sanctions for harassment. These provide the building blocks for a school climate that supports differences. Schools with healthy relations among diverse students “don't shy away from the issue of diversity and differences,” says Kreidler; indeed, “they look at these differences as enriching.” One school Kreidler cites hangs flags in the school cafeteria representing every country that served as the home of origin for a student's ancestors.

A multicultural curriculum is another prerequisite for racial harmony and understanding, Banks and others believe. When pupils study the norms and practices of various cultures—and learn how many different cultures have contributed to the American experience—they are more likely to understand and value diversity. Special attention in the curriculum ought to be given to issues such as racism, prejudice, and stereotypes. And such lessons should begin early, says Banks, because even young children are aware of racial and ethnic differences. The National Association for the Education of Young Children, for example, has published an anti-bias curriculum for preschool children.

Some experts believe that training students in the skills of conflict resolution or mediation can go a long way toward improving relations among different racial and ethnic groups. Conflict resolution programs allow all sides of a conflict to be aired, and they teach students how to use active listening to increase their understanding of the views of others. In mediation programs, students are usually trained to mediate disputes that have arisen among classmates. More than 2,000 schools use some form of conflict resolution program, according to one estimate.

Cooperative learning is also frequently cited as helping students of diverse backgrounds work together. Cooperative groups can help to reduce prejudice among students, particularly if students have equal status within the groups, says Banks. Ehrlich also supports such an approach. “You have to create opportunities in which diverse students are working together: where, to succeed, they have to work as a group,” he says.

Using such approaches before a race-related incident occurs gives schools a head start in ensuring a healthy and productive dialogue and, when possible, resolving the issues. “If you don't have anything in place when the incident occurs, all your energy goes into putting out the fire,” says Ehrlich.

Given that the student population will only become more diverse in the years to come, schools cannot afford to wait to build their capacity to improve racial understanding, says Bullard. For some students, she notes, their public school may be the most diverse place they'll be in their lifetime. If they don't learn the skill of getting along in school, she worries, they may never learn it.