I was determined that no February blizzard would prevent me from my first opportunity to talk about underachievement on national television. Travel from the Midwest to New York tested my own resolve to achieve success—but I struggled through the snow. Finally, in a five-minute segment on NBC's Today show, I described the epidemic problem of underachievement. After the show, I received more than 20,000 calls and 5,000 letters—confirming to me the existence of an underachievement epidemic.

The Carnegie Corporation's recent report, Years of Promise (1996), further certifies the seriousness of the underachievement problem in the United States. As the report states:Make no mistake about it; underachievement is not a crisis of certain groups; it is not limited to the poor; it is not a problem afflicting other people's children. Many middle- and upper-income children are also falling behind intellectually. Indeed, by the fourth grade, the performance of most children in the United States is below what it should be for the nation and is certainly below the achievement levels of children in competing countries (p. 2).

Definition of Underachievement

Most research defines underachievement in terms of a relationship between two scores; children's achievement test scores are below what their IQ scores would predict. This, however, is an inadequate definition. Because of test problems related to cultural differences, a rigid definition that compares only test scores grossly underrepresents the number of underachievers. When children underachieve over time, both IQ and achievement test scores may decline. Here is the definition that I prefer to use:Underachievement is a discrepancy between a child's school performance and some index of the child's ability. If children are not working to their ability in school, they are underachieving.

True underachievement problems are a matter of degree. Students who occasionally miss an assignment or don't study as hard as they probably should hardly ever cause anyone much grief. The underachievers who sit in U.S. classrooms and come to my clinic are capable of As and Bs but have report cards that often show Ds and Fs. What work they hand in is usually sloppy or incomplete; or they might complete it and then forget it or lose it. Some underachievers battle their teachers and openly refuse to do their work. They often blame others for their problems: teachers, brothers, sisters, mother or father, and sometimes even the dog.

Underlying the excuses are two main issues: Underachievers don't have internal locus of control, nor do they function well in competition. The lack of internal locus of control translates to a missed connection between effort and outcome; underachievers haven't learned about hard work. Underachieving students are often magical in their thinking; they expect to be anointed to fame and fortune. They want to be professional football players even when they have never played football; they strum the guitar hoping their unique sound will be discovered by a passing talent scout. They know they're smart because they've been told that by almost everyone. They just don't know how to be productively smart. If they put forth effort, they no longer have an excuse to protect their fragile self-concepts. They've defined smart as "easy," and anything that is difficult threatens their sense of being smart.

The competition problem is less obvious because underachievers often declare that they are good sports. It is their behavior that tells you that losing experiences make them feel like losers. They avoid any risk of losing and choose only activities or interests at which they are unique or best; but when they hit the proverbial "wall," they quit, drop out, or choose something else. Thus, a 13-year-old "hummer" (yes, hummer) explained that music was his life, and he planned to hum his tunes because he had already tried six months of piano, violin, and guitar, respectively, and they all became too hard. After all, there is no competition for "hummers."

Even success can stop these children if they fear their next performance won't result in first place. Some children develop writer's block after winning essay contests; or maybe an adolescent leaves the debate team after he's been the team's best debater. Underachievers habitually back away from losses and, therefore, don't build the resilience to cope with losing experiences, to see them as temporary. They feel permanently labeled "loser" if they don't do as well as others.

Causes of Underachievement

There are home and school causes of underachievement—usually occurring in combination. Overempowerment and "adultizement" can be important causes, especially for first and only children, children in single-parent households, or children of difficult divorces. Gifted children are also at risk of being given too much power too soon. Early health problems can also be a risk factor.

Lack of challenge or too much challenge in the classroom can cause problems, as can the overcompetitive or undercompetitive classroom. Children may say they are bored at school, but the term "boring" may also mask feelings of inadequacy.

Pressures that children internalize can also initiate problems. Sometimes those pressures stem from uneven abilities. Extreme praise by parents or teachers can also cause children to believe that adults expect more of them than they can produce. Perhaps the self-esteem movement has gone too far. Perfectionism can cause impossible feelings of pressure. Peer relationships can even cause pressures not to achieve. Informal labeling of the children within the family, such as "the smart one," "the jock," "the creative one," or "the social one," can cause competitive pressures.

Contradictory messages by parents are a major source of underachieving. If parents differ in their expectations, children learn escape and avoidance. A most lethal cause of student underachievement is parents' lack of support for schools and teachers. Disrespect for education by parents sabotages educators' power to teach.

Directions of Underachievement: Dependence and Dominance

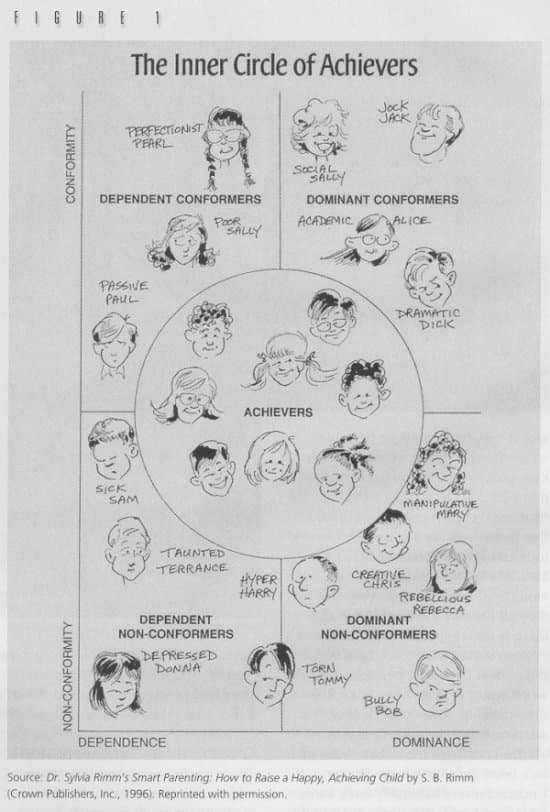

When children don't have the confidence to achieve in their school environments, they protect themselves by using defense mechanisms that work for them temporarily. They adapt by using dependent or dominant patterns. Parents and teachers may accidentally reinforce these defensive habits. Figure 1 shows prototypical children who reflect the characteristics of underachievement (Rimm 1996). These labels are not intended to represent actual children. Underachievers usually combine a number of the characteristics.

Figure 1. The Inner Circle of Achievers

The children on the left side of the figure are those who have learned to manipulate adults in dependent ways. Their words and body language say, "Take care of me," "This is too hard," "Feel sorry for me," "I need help." Adults in these children's lives listen to their children too literally and unintentionally provide more protection and help than the children need. As a result, these children get so much help from others that they lose self-confidence. They do less, and parents and teachers expect less. They become overanxious, oversensitive, and even depressed. They quietly slip between the cracks.

On the right side of the figure are the dominant children. These children select only those activities in which they feel confident they'll be winners. They argue or debate about almost everything. They manipulate by trapping parents and teachers into their arguments. If the children lose, they consider the adults to be unfair, mean, or controlling. Once the adults are established as unfair enemies, the children use that enmity as an excuse for not doing their work or taking on their responsibilities. Further, they manage to get someone on their side in an alliance against that adult.

Gradually, the children increase their list of adult enemies. They lose confidence in themselves because their confidence is based precariously on their successful manipulation of parents and teachers. When adults tire of being manipulated and respond negatively, the dominant children complain that adults don't understand or like them, and a negative atmosphere becomes pervasive.

The difference between the upper and lower quadrants in Figure 1 is the degree of these children's problems. Children in the upper quadrants have minor problems. They may adjust or outgrow the problems. If upper-quadrant children continue in their patterns, however, they will likely move into lower quadrants. Most of the dependent children will, by adolescence, change to dominant or mixed dependent-dominant patterns. Some children combine both dependent and dominant characteristics from the start.

Parents and teachers feel frustrated because they can't seem to break these patterns of dependence or dominance; instead, they reinforce the patterns. Although they should certainly listen to these children's words, parents and teachers need to interpret them in ways that will be productive for the children in the long term, even if this causes some temporary discomfort. It's important for adults not to empower children so much that guidance is impossible. If they listen to children's messages and reframe their views to give them more appropriate direction, children will accept their leadership and develop the skills and confidence they need to establish their own identities.

Adults do much of their parenting and teaching intuitively. Intuition works well if they've been parented and taught well themselves. Intuition works well with children who are positive and are learning and achieving. However, for adults who do not see their early family life or school life as having been productive, their intuitive sense may lead them astray. For children exhibiting dependency and dominance, counterintuitive responses may be more effective. Intuitive responses have already proven ineffective.

Children should be encouraged to develop independence and creativity. It is only the extremes that lead to dependency and dominance. When children complain, whine, or are continually negative, or when they request help more frequently than they need it, they're showing symptoms of too-dependent relationships. If they are creative only for the purpose of opposing, or if they insist on wielding power without respect for the rights of others, they are too dominant. These extremes will result in underachievement at some level.

Thus underachievement is a collection of symptoms, and underachieving children will cause other family and relationship problems. Underachievement can be reversed, and parents and teachers can help children modify their own expectations and develop the confidence to live more satisfying, resilient, and productive lives.

Reversing Underachievement

At the Family Achievement Clinic, we reverse underachievement in roughly four out of five children by using a three-pronged approach called the Trifocal Model, which focuses on the child, the parents, and the school.

The Trifocal Model includes six steps. Assessment is the first important step, leading to communication with parent and child, identification of the child's profile, and changing parent and teacher expectations. The final step presents home and school modifications and strategies for both dependent and dominant children. In the clinic setting, the average reversal time for underachievement ranges from six months to a year, depending mostly on the patience and perseverance of parents and teachers (for step-by-step instructions in using the Trifocal Model, see Rimm 1995).

Many parents and teachers have reported that by following the model, they have corrected problems and have improved children's achievement. Although it is possible for teachers or parents to work alone, the strategy is most effective when they cooperate with one another. The Trifocal Model has been used effectively for children in kindergarten through grade 12 in regular education, special education, at-risk programs, and gifted programs.

The model includes practical strategies for parents and teachers. Some strategies for teachers include teaching to multiple learning styles; teaching students about challenge, competition, cooperation, and acceptance of criticism; using intrinsic motivation; forming a student-teacher alliance; teaching concentration techniques; learning anti-arguing routines; and giving children an audience.

For example, for dominant, nonconformist adolescents—often the most difficult underachievers to turn around—teachers and parents can plan activities that appeal to kids' strengths and build up areas of weakness. Suppose that "Manipulative Mary" (see fig. 1) is a strong reader but a poor writer. Reading to children in lower grades (giving the teen an audience) would effectively allow Mary to use her strength; writing stories for the same children (using intrinsic motivation) would challenge her to improve her weak area.

Another approach that teachers—or parents—can use with this often oppositional teen is to learn anti-arguing strategies. If "Creative Chris" starts an argument during class or in a peer-group setting, ask him to talk with you about it after class or when he doesn't have an audience; you cannot expect a positive solution when the teen's peers are around. If Chris wins the argument, you lose. If you win the argument, you also lose, because the sympathy of the peers will likely be with the teen and against you (the "mean" adult).

After class, listen to the teen and try to arrive at a compromise or a win-win solution, even if you have to tell him, "Let me think about it. I'll get back to you." If the solution doesn't work, the teen will have renewed respect for you because, first, you listened, and second, you did not immediately give in—you weren't a "wimpy" teacher. You will have encouraged creative thinking and shown your respect for the teen as a person.

- Overreaction by parents to children's successes and failures leads them to feel either intense pressure to succeed or despair and discouragement in dealing with failure.

- Children can learn appropriate behaviors more easily if they have an effective model to imitate.

- Deprivation and excess frequently exhibit the same symptoms.

- Children feel more tension when they are worrying about their work than when they are doing that work.

- Children develop self-confidence through struggle.

High Expectations, Parent Support, and a Work Ethic

Although there is no simple answer to the complicated question of underachievement, we can use the Trifocal Model as a framework for some principles that we know underlie good learning. If parents have realistically high expectations, if they respect teachers and teachers respect them, and if children can be taught a healthy work ethic, despite the multiple problems in our society, resilience and achievement can be taught. As parents and educators, we must accept our leadership responsibilities. If we can build children's confidence and competencies, we can empower them gradually as they grow in maturity and wisdom.