Another long day at Margate Middle School came to a close. I was in my third year of teaching 7th grade science, English as a second language, and computer applications at this diverse, Title I school outside a metropolitan area. Our adolescent students finally cleared the halls, and I lingered outside my door to chat with my neighboring teacher.

As our conversation wrapped up, Kim, a fellow 7th grade teacher who was a Caucasian woman, rounded the corner, eyes brimming with tears. Kim and I shared a common student, an African American girl named Alicia. Alicia wasn't perfect, but I found her to be a hard worker, detail oriented, and charismatic in my science class. However, Kim had a different experience of Alicia; they often bumped heads during class. Now, as she approached, she proclaimed, "I just don't know what to do with Alicia!"

Her statement was disconcerting to me. Kim was close to retirement. I wondered how a student could work well with me, an early-career African American teacher, but have a difficult time with Kim, an experienced educator.

As my months working at Margate (a pseudonym) went on, I noticed many other students who worked well in my class but gave other teachers a run for their money. Many, although not all, were students of color. In spring 2013, Margate and its surrounding district in the upper Midwest had been identified by the state for disproportionately disciplining BIPOC (Black, indigenous, and people of color) students. I found myself wondering if there were connections between our students' race or backgrounds and how effectively particular teachers (of any race and background) interacted with them when student behavior was perceived as challenging.

Having a background in English as a second language, I knew that my connection to my own culture, as well as appreciation for other cultures, helped me form relationships with students, which often led to better behavior. However, I also recognized that the fact that many of my students shared my race and background wasn't the only reason many students had academic and behavioral success in my class. I knew of both white and BIPOC teachers who struggled with classroom management. I began thinking about teachers like Kim, along with the school's disproportionality status, and realized many of our teachers must lack the skills, confidence, or both to successfully reach students of color.

I didn't feel like an expert, but wanted to be a part of the solution. I sought several like-minded colleagues, who I knew had good rapport with students and were also passionate about issues related to diversity, equity, and inclusion, and asked them if they would like to form a working group with me, geared toward effectively educating students of color. Ten or so of us met for several months toward the end of that school year. (We met privately at first to avoid potential backlash from teachers at our school who felt race was unimportant—of which there were some—but we soon opened the group to anyone interested.) We called our group "Successful Strategies," because we wanted to focus on skills teachers could use in their classrooms to better serve students of color. After much discussion surrounding the current racial climate of our school system, disproportionate discipline, and the history of race in our area, we chose this mission statement:

To support our [marginalized] populations through building relationships and connecting with their families, teachers, and support staff. Our hope is for this [work] to translate into positive behavior, academic success, educational equity and to ultimately transform our school culture/climate.

Our group was geared toward effectively educating BIPOC students, and we didn't want to limit the strategies we learned to those in our group. We wanted to grow together, share our findings with our larger school community, and usher in change in our overall pedagogical practices.

At the end of the year, I presented our work to Margate's principal and asked if we could be considered an official after-school professional learning community (PLC) for the coming school year. He agreed wholeheartedly.

Those of us on the committee felt many of our staff members weren't yet readily open to equity work. So that summer, as preparation, we made available to Margate educators a training centered around strategies for educating students of color, specifically African American males, run by a diversity-focused education consultant connected with our district. Grant funding paid teachers to attend this several-day series of sessions. Most of Margate's teachers took part in this opportunity, learning more about Black culture, the problems inherent in deficit thinking versus strengths-based approaches, and the psyches of Black males. The training became a foundation for our group to do powerful work in the approaching school year.

Building Efficacy—Almost Without Realizing It

During that school year, our committee periodically presented at staff meetings, sharing what we learned about the effects of bias on classroom management, racial inequities in education, and instructional approaches that would likely work well with BIPOC students. We supported teachers in working with marginalized students, for example by making available sets of books related to culturally responsive teaching and encouraging staff to use restorative practices.

Although we didn't realize it at the time, our group was engaging in "collective efficacy." Goddard and Goddard (2001) define collective efficacy as "the perceptions of teachers in a school that the faculty as a whole can organize and execute the courses of action required to have a positive effect on students" (p. 809). Bandura (1992) argued that when a school faculty has a collective sense that they can promote students' academic progress, this contributes to students' actual level of achievement. Teachers influence one another's confidence that they can make a difference, which impacts overall school achievement, climate, and culture.

Ultimately, our decision to work together to improve teachers' practices made this kind of impact. Over the years I led the group, we grew as culturally relevant educators by forming a safe space, engaging in self-reflection, acknowledging race, collaboratively influencing our colleagues, and celebrating small victories. Teachers at the school who weren't members of our PLC also grew in their efficacy in working with BIPOC students, by trying out the many strategies those in our group shared in all-faculty meetings and by deepening their understanding through new perspectives and chances for reflection that we offered. Teachers spoke about how their practice changed, especially in working with marginalized learners. For instance, one said:

I would take out [the list of] sentence starters whenever I made phone calls home [and] purposely use each one during the conversation. It help[ed] make a positive impact, and really made it feel like the phone call was one of partnership/working together, and not of defense/deny.

Solidifying a Safe Space

Our group was teacher-created and teacher-led, which made it authentic and organic. Although administrators and support staff attended committee meetings, the PLC remained teacher-driven. Within meetings, administrators put down their leadership hats and allowed me to lead collaboratively. During my time at Margate, the district forced initiatives and curriculum changes that rubbed many teachers the wrong way, but there was never any real resentment about Successful Strategies because our staff knew it was teacher-led.

The authenticity of the group, along with the norms we established, such as confidentiality and assuming positive intent, allowed colleagues to let their guards down and grow together. One of the most important things to me was that staff felt relatively comfortable as we embarked on the journey of cultural competency. Whatever was said during our meetings wasn't judged. Teachers were allowed to be fully human and to be learners instead of subject-matter experts. There were no stringent membership requirements. Our schedules were packed, so I tried to be understanding when attendance ebbed and flowed throughout the school year. We adjusted our learning directives based on the needs of participants.

Looking Within

The Successful Strategies group made its debut presentation at our school's welcome back in-service meeting in fall 2013. We restated our goals and shared information on our school and district's disproportionality discipline status. With all colleagues now aware of us, over the next few months our PLC grew to include administrators, support staff, and teachers with a variety of years of service, teaching disciplines, political backgrounds, races, and ethnicities. Some were well-versed in cultural competencies; others were just beginning their quest to teach more equitably. However, we were all dedicated to being part of the change, learning and sharing best practices for educating BIPOC students. We hoped that in coming together monthly, we could learn from one another. We also realized that making instruction more equitable required us to look within.

One of the first books we read together was Motivating Black Males to Achieve in School and in Life by Baruti Kafele (ASCD, 2009). We enjoyed the brevity and pace of the book; chapters were short enough for busy teachers to read, yet power-packed and insightful, and each chapter contained reflection questions. We used various questions to guide our discussions, but one particularly resonated, becoming a constant point of conversation for months. That question—Do I see myself as the number-one determinant of my Black male students' success or failure?—sparked heated conversations and led to some vulnerable moments.

We knew there were factors significantly present in students' lives—poverty, homelessness, trauma—that could lower achievement and lead to behavioral challenges. It was easy to conclude those factors were unsurmountable barriers. But through discussion, teachers came to grips with the weight of being an educator, someone who could be the top factor in how any student learned within school. One said she understood "what a tremendous impact I can have on students, especially Black males. I will make sure I don't diminish their fire, but spark and encourage them."

Reading this book helped us realize that before we could address the needs of students of color, in this instance Black males, we had to collectively look within and admit that perhaps we'd failed these learners. Once we accepted this, we took personal responsibility. We encouraged one another to see ourselves as the number-one factor in the academic achievement of Black males in our school.

Acknowledging Race and Bias

Something else we did was learn to acknowledge race and dismantle colorblindness, a model that "treats race as [an] irrelevant, invisible and taboo topic" (Howard, 2006, p. 57). Colorblindness comforts those who are privileged while denying "the authentic existence of people whose experiences of reality [are] different" (Howard, 2006, p. 58). Individuals who claim to be colorblind see race as something that can be easily erased and ignored to establish equality.

Many of our coworkers were proud of "not seeing race," but as we continued our group reads, we gained a deeper understanding around the concept of identity. To understand our students better, we did the work of exploring our own racial histories, using How to Teach Students Who Don't Look Like You by Bonnie M. Davis (Corwin, 2012) as a guide. Once we understood our own racial histories, we were equipped to understand the cultural backgrounds of our students and how culture shaped their identities. We worked through guided group discussions using reflection prompts from the book. We later passed some of the strategies offered in each chapter on to the rest of our colleagues during staff meetings.

Many Margate staff members were hesitant to recognize race when working with students of color, for fear of being labeled "racist." One year, some of our group members, including myself, attended an anti-racism institute where we learned that racism is not a binary concept, but a spectrum (Cristiln, 2019). We all fall somewhere on the spectrum, from the extreme end of having beliefs that could lead a person to engage in terrorism against someone from a certain racial group to the other side of pursuing liberation for everyone. I learned that as a Black woman, I had taught myself to conform to some racist systems in society instead of being willing to take a stand against them. Coming to terms with racial biases helped us encourage our staff to overcome the fear of being a "racist," and instead work through the spectrum toward liberation.

Strengthening Each Other

Our group's collaborative leadership style helped strengthen our collective efficacy, because many of the committee's efforts were ideas that we decided upon together. We had equal input into our activities and presentations. During our initial meetings, we discovered the strengths of each member of the group, and we used these strengths when presenting to fellow teachers and staff members.

Regular presentations to the wider faculty at Margate, usually at required faculty meetings, were the main way we helped build all our teachers' collective efficacy. We carefully thought through how to use this presentation time to build others' efficacy. Most of us within the group deeply believed the best way to be culturally competent was to spend significant time doing self-identity work and become liberated from colorblindness. However, we also understood the constraints of our time at staff meetings didn't permit us to guide others to do the necessary deep digging within a meeting—and of course, our committee was called Successful Strategies. So, we spent a small portion of our time reviewing the reasoning behind culturally relevant practices, while allocating most of each presentation to hands-on, practical strategies teachers could apply within classrooms.

We hoped that in coming together, we could learn from one another in a safe space.

Kel Hughes Jones

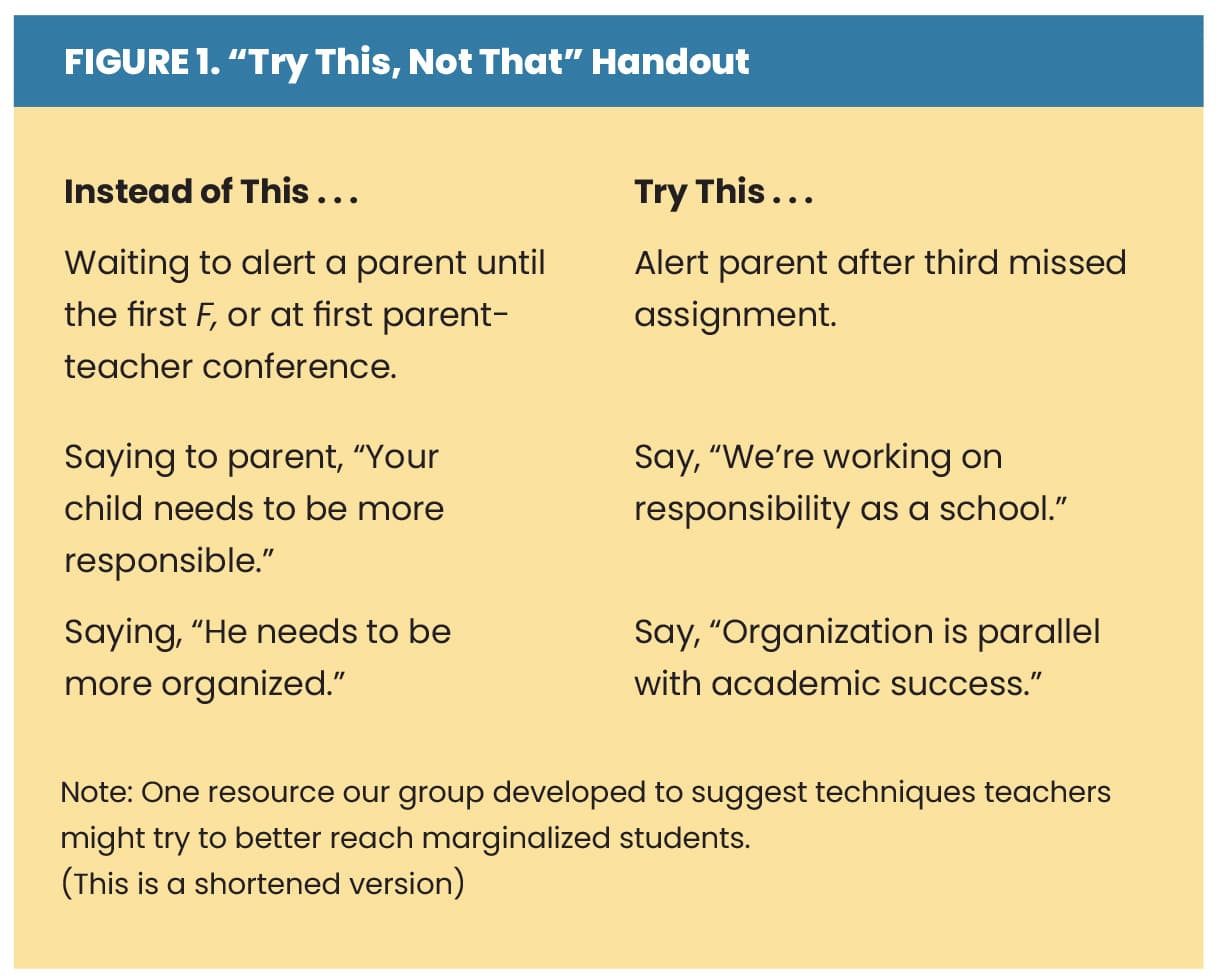

Each of us took an active role in presenting. Those who desired to remain behind the scenes contributed in other ways, such as by creating materials to help build teachers' understanding and efficacy. One handout we created several versions of was "Try This, Not That" (see fig. 1). On one side we listed an action, statement, or classroom management technique that wasn't culturally relevant, and on the other side, one that would better serve students of color.

In our presentations, we also used discussions and role-playing. We took turns promoting discussion in the faculty meetings, using questions from texts we were reading, such as, What compelling similarities and differences do you find in your racial history and the racial histories of others? or Do I plan each day thoroughly, with a view toward the success of my Black male students? We modeled for peers and then let them try two ways to do a key practice—one that would likely alienate students of color and a more culturally sensitive way—sometimes deliberately showing practices at each extreme to get the point across. For those in our group who were animated, role-playing became their favored way to contribute. One of our best role-playing sessions involved demonstrating positive phone calls home, which many staff outside our group were eager to try out.

Over the years, our Successful Strategies group felt empowered with each presentation. We perceived we were slowly making a difference to our larger school community.

Celebrating Victories

The transformative work of fostering culturally responsive teaching doesn't happen overnight, nor even in the course of one school year. In the five years that I led the committee, my school and district continued to face racial problems related to the discrimination of Black students and staff members. However, our group focused on doing the work and becoming a beacon of light to teachers struggling to do right by students of color. Part of what inspired everyone was celebrating small "wins" along the way—even just the "win" of creating a safe environment to reflect together while we supported one another, or of realizing that a role-play to model culturally relevant teaching practices led to teachers trying those practices in ways that improved teacher-student relationships.

Arduous and Rewarding

Diversity work in educational systems is an arduous yet rewarding journey that can become easier and more bearable when working collectively with allies. Instead of focusing only on the challenges, our professional learning group often affirmed what we were doing right together, and how we were improving. As we grew, we had the reward of seeing our actions impact the achievement of students of color.

Note: All teacher and student names are pseudonyms.