Why do some youths overcome seemingly insurmountable odds during childhood to become productive and happy adults? With dozens of strikes against them, how do they manage not only to survive but to thrive?

Increasingly, the term used to describe the critical factor that some youths possess is resilience. Resilience can be thought of as an antibody that enables them to ward off attackers that might stop even the most formidable among us. Clearly, no one could question the value of giving children, especially those most at risk, such an antibody. But can we realistically do so? In my visits to effective schools throughout the United States, I have seen ample evidence that we can. More important, these visits have convinced me that all schools should commit themselves to building resiliency in their students.

What Is Resilience?

I define resilience as the set of attributes that provides people with the strength and fortitude to confront the overwhelming obstacles they are bound to face in life. What are some of the characteristics that set resilient children apart from their at-risk peers? Experienced educators have an intuitive ability to spot these students. I often ask teachers to describe resilient students. Here are descriptors that were brainstormed by classroom teachers in a workshop I recently conducted: social, optimistic, energetic, cooperative, inquisitive, attentive, helpful, punctual, and on task. Not surprisingly, these are some of the same characteristics described in the literature on motivation (Pintrich and Schunk 1996).

provide them with authentic evidence of academic success (competence);

show them that they are valued members of a community (belonging);

reinforce feelings that they have made a real contribution to their community (usefulness); and

make them feel empowered (potency).

Instilling these positive feelings in students will not result from pep talks or positive self-image assemblies but, rather, from planned educational experiences. Simply put, we must structure opportunities into each child's daily routine that will enable him or her to experience feelings of competence, belonging, usefulness, potency, and optimism.

What Schools Can Do

Many of the building blocks of a CBUPO-rich school experience are already present in most schools. In fact, if we shadow some of our most successful students, we will likely observe them participating in such activities.

Rather than developing new strategies, therefore, we must become more strategic and deliberate about some of the good things we are already doing. Specifically, we need to examine why some students are benefiting from resiliency-building experiences and others are not—and plan strategies to make these invaluable feelings available to everyone.

A starting point for schools is to develop a CBUPO inventory. When I am working with a school, I ask the faculty to brainstorm practices that have the potential for building feelings of competence, belonging, usefulness, and potency. The results of such a brainstorming session often look something like the list in Figure 1.

Building Resiliency in Students - table

Organizational/Instructional Practices | Trait-Reinforced |

|---|

| Logical Consequences | Potency |

| Mastery Expectations | Competence |

| Service Learning | Usefulness |

| Cooperative Learning | Usefulness |

| Teacher Advisory Groups | Belonging |

| Authentic Assessment | Competence |

| Student-Led Parent Conferences | Potency |

| Learning Style-Appropriate Instruction | Belonging |

| Activities Program | Belonging |

| Portfolios | Competence |

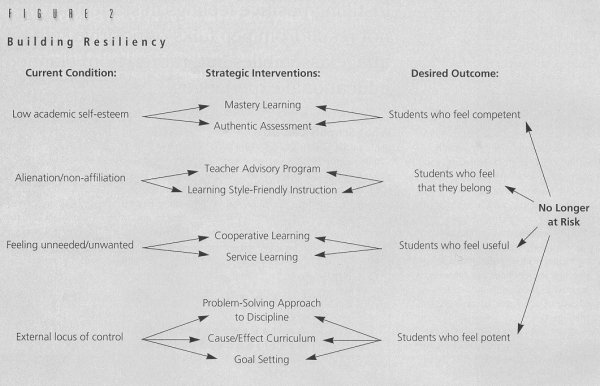

After generating such an inventory, a faculty's next task is to visualize the rationale for their efforts through a map or web of the relationship between strategies/interventions and expected consequences. Frequently, school teams will spend weeks talking, thinking, and negotiating ideas until a picture finally emerges representing their consensus. From my experience, the time invested here is well spent, because it can result in a schoolwide approach with deep staff ownership. A completed web might look like the one illustrated in Figure 2. This particular web is a composite drawing derived from my work with several schools.

Figure 2. Building Resiliency

A web can be considered complete when the theory it illustrates is logical and clear enough that most staff members are prepared to say, "I think this will work!" Once a web passes that test, staff can begin putting their strategies into practice. At this point, however, the work of the planner is far from done.

The Role of Data and Assessment

If the goal is to build resiliency for all students, then a deliberate and disciplined assessment effort is necessary to determine whether the desired results are being achieved. Assessment is critical, as even the best programs may miss many of the students who need them the most.

For example, an athletic program may be a key element of a school's resiliency-building efforts because it builds a sense of competency and belonging. Faculty must, however, regularly audit the program to ensure that it is, in reality, serving all students. A simple sorting of data by ethnicity could alert them to important trends. They might ask: Are Hispanic students involved in the program at the same rate as white students? Are both genders being equitably served through athletics? Are remedial students, those with disabilities, or those coming from low-income homes receiving the same opportunities as more advantaged students?

How can we determine whether all students, regardless of achievement level or ethnicity, felt encouraged and supported while preparing for and conducting their conferences?

Did participation in the student-led parent conference program contribute to enhanced feelings of potency for these students?

Once faculty members have assembled and analyzed all the relevant data, they are ready to ask the ultimate evaluative question: Are we getting the results we hoped for? If students are exhibiting evidence of greater feelings of competence, belonging, usefulness, potency, and optimism, they should be delighted. It is possible, however, that even if all students have fully experienced an intervention, desired outcomes may not have occurred.

As educators, we need to avoid being defensive about data. Information that a treatment didn't work for a particular patient doesn't necessarily mean the doctor was incompetent. Rather, it indicates to the competent doctor that it would be wise to employ another approach. Likewise, if our data show that in spite of our best efforts, our students are still feeling academically incompetent, alienated, useless, or powerless, we should be willing to openly question our theory and try alternative strategies.

Consistently conducting action research and reviewing assessment data does for educators what computerized rocket telemetry does for NASA. It helps us determine whether we are on the right track and, if not, what corrective actions we should take. By continuously constructing and testing our theories on resiliency-building, it is much more likely that we will ultimately be able to supply our students with the antibody of resiliency.

The Matter of Time

Building resiliency in students need not take substantial time from teachers' other instructional pursuits. A lot of the techniques are likely already part of many teachers' repertoires. But, more important, feelings of competency, belonging, usefulness, potency, and optimism result from authentic experiences. Deep down we all know that assemblies, classroom posters, and happy face stickers cannot change a student's attitude toward school or life outside of school. On the other hand, infusing the classroom and the curriculum with resiliency-building experiences can have a profound impact on our students' self-images. When taking this perspective, we begin to see that building resiliency and teaching are one and the same thing.

Likewise, assessing the efficacy of resilience-building interventions shouldn't require expensive, time-consuming evaluations. This is because the best source of data on student attitudes is close at hand: the students themselves. While specific evaluation strategies will differ by teacher and context, a simple strategy will illustrate how easily data can be assembled.

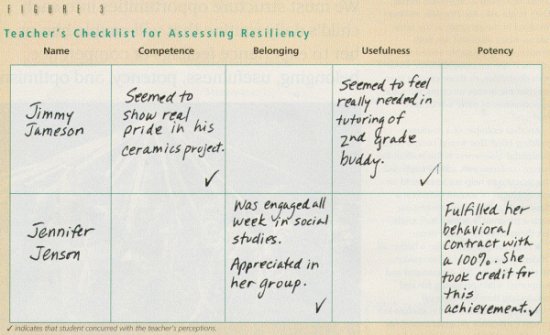

Teachers could use a checklist, like the one illustrated in Figure 3, as part of their plan book. By filling it out weekly, teachers can keep track of their perceptions of how targeted kids are feeling about class activities. Then, on Friday, they can confirm their perceptions by talking with the students. This simple procedure can turn assessing the development of resiliency into an almost routine classroom ritual.

Figure 3. Teacher's Checklist for Assessing Resiliency

An Uncertain Future

As adults, we would love to ensure that the world our children inherit will be better and brighter than the one we now occupy. Unfortunately, that's not possible. Life's obstacle course will continue to exist for our children, as it has for us. What we can do, however, is use our school programs, our teaching strategies, and our methods of classroom organization as vehicles to respond to the challenge raised by Franklin Roosevelt more than 50 years ago: "We cannot always build the future for our youth, but we can build our youth for the future" (1940).

I am convinced that the best way to prepare our youth for an uncertain future is to provide each student with a resiliency antibody. We can do this by providing them genuine feelings of competence, belonging, usefulness, potency, and optimism through powerful, repeated, and authentic school experiences and by critically examining the results of our efforts.