All educators wish to create strong relationships with the families we serve. But we may not realize that some of the common practices we use to build those relationships actually get in the way of true partnership. Consider the most common activities schools offer to families. We host back-to-school nights, develop family workshops to teach student support strategies, and provide updates on students' progress through parent-teacher conferences. We often assume if families have a better understanding of what is going on at school, are provided with resources to help their child, and get a chance to hear about their student's academic progress throughout the year, then we've done our job in creating partnerships with families.

And yes, these activities can be beneficial. But they can also reveal structural problems in our approach as well as relational blind spots. These issues can manifest in conflicts that often remain beneath the surface. Engagement during conventional family-engagement meetings is often unidirectional, tightly controlled, and aimed at short-term impact. Such offerings are school-centric in nature and implicitly (and in some cases explicitly) communicate that the school always knows best (Khalifa, 2018). After back-to-school night (in which families don't often have the opportunity to actually speak with teachers), contact with families may not happen again until there is a sign of trouble—when a child is not living up to the teacher's implicit aspirations. We as experts present the problems—such as a student not listening or, in the time of the pandemic, a student missing online instruction—and the family is expected to either provide or implement a solution. This sets us up for a cycle of short-sighted challenges and blame-game conflicts and provides little space for shared ownership and collaboration.

Can They Trust You?

But with a few shifts in perspective and intention, family-teacher relationships can blossom and make a huge difference in a student's learning. Teachers must get beyond the one-way communication activities we've relied on for so long and develop trust and mutual respect with the families we serve.

When examining your school's approach to family partnerships, it is essential to keep in mind that the challenges I'm describing have a disproportionate impact on students who have been pushed to the margins. It isn't just the fact that conventional parent-engagement efforts limit the opportunity to address inequities in student outcomes. They also disregard an important historical context: Families who have been marginalized have little reason to trust educators. Not because we have bad intentions or wish to do wrong by children, but because our system has shown time and time again that schools can be places where students at the margins can experience great harm. At the inception of this country, Black students were in danger of being physically harmed and even killed if they were seen reading (Howard, 2015). Today, Black students are least likely to be recommended for gifted and talented programming unless their teachers are Black (Barshay, 2016; Dreilinger, 2020). Indigenous students have historically had their cultures stripped from them in residential schools, and even today less than 50 percent of states require integration of indigenous history in curriculum (National Congress of American Indians, 2019). The results of equity audits happening all across the country often illuminate how marginalized families experience hostility, dismissiveness, and an overall lack of belonging in schools. It's no wonder that many families have a lack of trust in educators.

While it may be difficult to navigate, this legacy of neglect is not something educators should feel shame around. There is power in educators acknowledging that they have not yet figured out how to best support each or all the students in front of them. We don't always know how to hold high expectations, provide support, and nurture positive attitudes, and because of these gaps we are prone to make mistakes. This is why we need family partnerships. This is why relationships matter from the beginning.

Building a shared understanding of mutual goals can help us reshape how we partner with families now and in the coming years. True family partnership is concerned with building reciprocal relationships, shared responsibility, and joint work across settings and is focused on benefitting the learning and development of children. The underlying belief is that to best support a child, we must get to know each other, create a shared picture of student goals and needs, and engage in collaborative activities like problem solving.

Asking for feedback and inviting ideas helps to create true partnerships that will lay a foundation for the entire school year.

Establishing Goodwill

Many relationships between teachers and caregivers were already strained before the pandemic.

As a result of various stressors from the past two years on both families and educators, anxiety about working together now is likely even higher. Families want to know educators' intentions for their child. They can't read a teacher's mind, and in some cases, it is plausible that minoritized families will assume educators' intentions involve low expectations for their children and a readiness to dismiss their humanity and potential. Teachers, on the other hand, often feel overwhelmed with how to create partnerships with families—they are often expected to do it on their own time or feel they have to go beyond the scope of their working hours to create relationships and aren't given enough guidance or support to do so. And yet, for families to feel different, they must see educators act differently. Educators must make it clear to families that it is their duty to be the first to establish goodwill.

But such interactions do not have to always be large, time-consuming steps. Small yet meaningful actions to establish goodwill can create new expectations and begin to establish trust. Reach out to all your families early in the year with a quick phone or video call to establish a relationship. If some of the families speak a different language than you, this can admittedly be trickier. In this case, written communication with translation, or asking a translator to be on the calls, is the best solution. Be vulnerable and share your intentions as a teacher. Be specific about the ways you plan to get to know your students and about your academic goals for them. Inquire about caregivers' goals for their students and find commonality.

Ask meaningful questions like: What does it mean to them for the school to have high expectations for their child? What would they want you to do to set and reinforce the expectations? What do they need from you? What can you ask of them? What cultural practices are important to them? What is important to their student that often gets left out of school? Engaging in authentic dialogue like this lays the foundation for shared ownership and a focused, generative relationship.

Then, six to eight weeks after that initial phone call, call your families back. This time, share the ways that your first conversation affected your instructional planning. Ask them for their feedback on your practice and their students' experience. Ask questions about how you can better support their child. It can be quite exciting for families to hear about an upcoming unit and have the chance to share about ways you can elevate their students' full identity, cultivate joy, and raise academic expectations. This practice will provide routine and coherent ways to connect with families.

This type of dialogue should also be a feature of back to school night events that occur several weeks into the year. Instead of solely sharing what you plan to do during the school year, carve out some time to share vision and goals, and invite families to share their perspectives. You can offer a quick get-to-know-you activity that showcases all the different cultures represented in the classroom and ask families to brainstorm how they might celebrate and honor the rich perspectives and experiences students bring to the classroom. This community brainstorming builds on connections from smaller meetings and allows families to also build relationships with each other. Asking for feedback and inviting ideas helps to create true partnerships that will lay a foundation for the entire school year.

School leaders should create time in professional learning spaces three times a year for teachers to come together and apply caregiver feedback to their instruction. Teachers should have time to review family feedback and later check-in on how they've implemented it and what the results have been.

Focus Interactions on the Child

Though educators may believe their students are the focus of any conversations or events with families, this is not always the case. In my work, I've seen good intentions of teachers set aside when other tasks take priority, or conversations derail into vague notions of support or general advice that does nothing to build true relationships with families to better support their child.

In the beginning of the year, teachers plan many activities to get to know students. We often "partner" with families by having them fill out surveys about the strengths and weaknesses of their child and hope to use this information to know how to best serve them. After the first few weeks of school, however, the surveys often get placed in a filing cabinet and getting to know students more deeply is sidelined for the "serious stuff"—academic content. And in the event that a child does not get on board (for example, misses an assignment or misbehaves), we quickly move to negative phone calls, which begins the cycle of relational challenges highlighted earlier in this article.

The family-teacher conference, usually held at report card time, is another activity where, strangely enough, the focus is often not on the child. The conference is usually about 15 minutes long and structured as follows: The teacher states that the conference is about figuring out how to best support the student. The teacher shares some strengths ("He is good at contributing to the class," or "She gets along well with other students") followed by weaknesses ("They struggle to pay attention," or "She isn't on grade level in reading"), often with little or no student work shared. After the educator has laid the "facts'' on the table, the parent is left with two minutes to ask questions. The conversation is unidirectional, the student experience and needs are unclear, the advice for parents is often vague and unhelpful, and the focus is not actually on supporting the child.

For a true family partnership to develop, these interactions need to go much deeper. The spirit should move from sharing progress (or lack thereof) to co-constructing meaning. The teacher might share her goals first, but also give caregivers ample time and space to share their goals and concerns. Together they should look at student work, identify where they see progress and goals met, and discuss how they can work together to build on what's been accomplished. By the end of the conference, both parties should leave with concrete actions (The teacher might say, "I will increase positive interactions with three affirmations to every one redirect" and the parent might say, "I will preview the schedule for the day at home and encourage her effort at writing time"), and they can discuss the impact of these actions during a follow-up phone call. This type of conference continues to establish goodwill because it is clear to families that the educator's intention is to partner with them to meet the needs of their child.

To make these kinds of interactions effective and impactful across the school, educators must also work as a team to use the feedback they get from families to inform their instruction and lesson planning. When I was a kindergarten teacher, I realized from my calls home that our families were often looking for ways to get involved with the school. I brought this knowledge to my grade-level team, and we created a menu of activities that families could participate in. We embedded these activities into the calendar, so there was a specific day, for example, when families could come to the classroom to share family stories, another day where they could bring in books to read with students, and other opportunities for them to chaperone field trips to important places in our immediate community. Students found it just as enriching to go behind the scenes at a local family-owned ice cream shop as trips to locations further away. Listening to your families is one step—but taking what you hear and working with your team to apply this knowledge and make changes is critical.

The Power of Admitting You Don't Know

One thing that the pandemic has taught us as educators and school leaders is that we don't all have the answers. We are in unprecedented territory, and it will take all hands on deck to move forward. This is where the power of family partnership can truly come alive. Recently, I was in a school with several educators who are also parents. One asked, "I want to know what kinds of activities can be designed that make my child want to get out of bed."

Both parents and teachers are wondering the same thing! And there's a power in admitting you don't have all the answers. When families and educators do come together and brainstorm answers around a central question in a way that nurtures dialogue and shared ownership, the solutions are always richer. And when we create those opportunities with families who have been othered or minoritized in mind, we have more opportunities to increase inclusivity.

Teachers must get beyond the one-way communication activities we've relied on for so long.

One of the most powerful experiences I had as a school leader was when I worked with families whose students had Individual Education Plans to identify proactive ways to nurture positive student-educator relationships and ways to redirect when relationships were becoming negative. I met with a group of families and shared my ideas and a potential plan. I asked, What is missing from the plan? What did we not think of? Are there places we could unintentionally harm students with specific needs? I was transparent that I wouldn't move forward without getting to a place we felt good about as a collective. The families were extremely grateful to be heard and to see the policy enhanced in real time as a result of their thoughts. When they pointed out that the plan did not make room for differentiation, we brainstormed how it could. It was scary to be this vulnerable, but this is how we move from seeking input to sharing power.

A Shared Goal

The pandemic continues to present many unanswered questions for schools, so providing families an opportunity to co-construct possible answers brings authentic partnerships and the pursuit of a shared goal—student wellness and success and positive experiences.

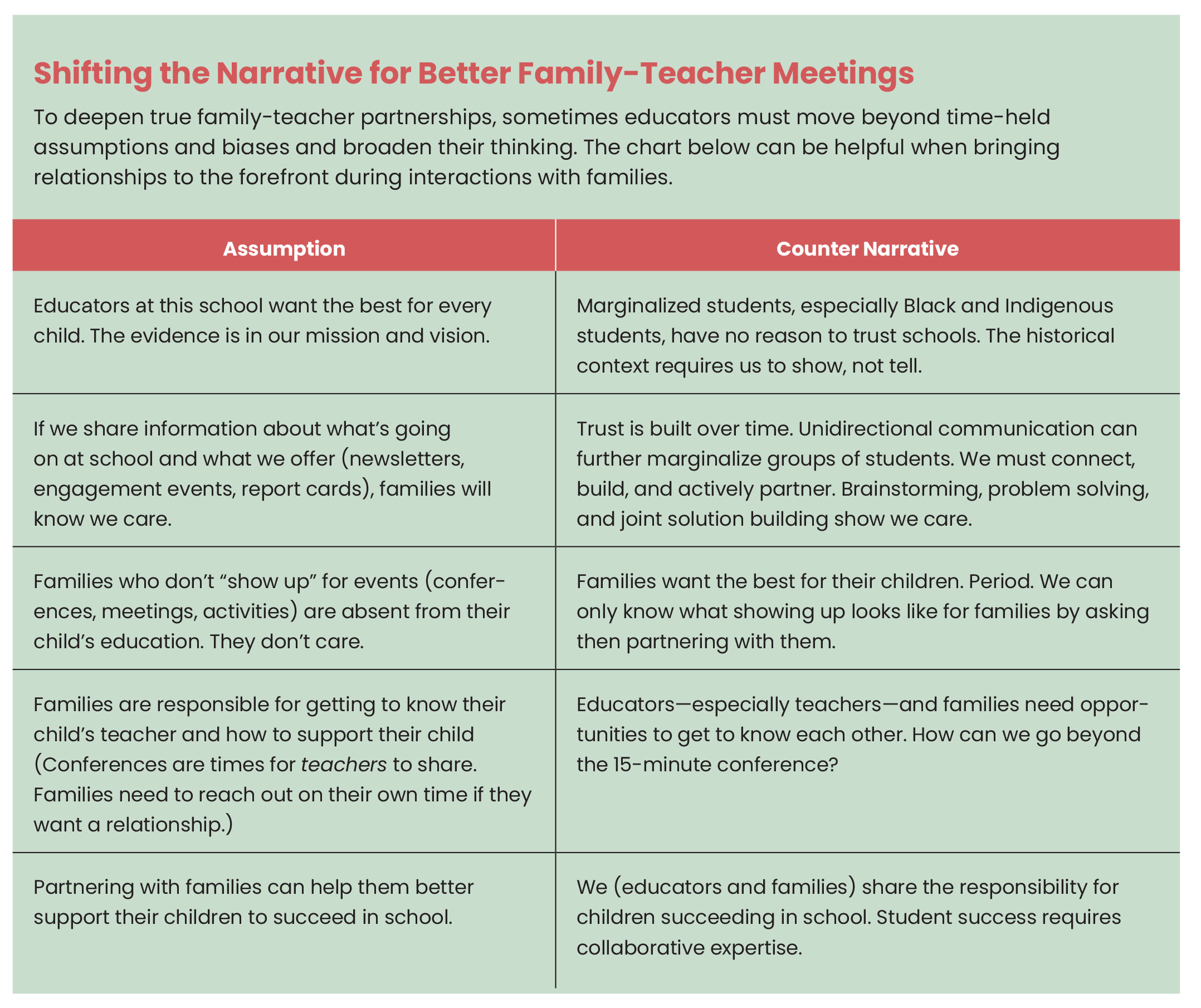

If we begin to take a relational and structural approach to family partnerships, we have the chance to chart a new path in our approach to educating students. Underneath these strategies is a requirement for us to challenge long-held assumptions about power dynamics, whose voice matters, and whether or not all families care about their child's experience in school. To disrupt those assumptions, we must own our historical context, try new things, and move through this new territory together in the hopes that we lead toward family partnership with the journey of working toward equity in mind.

Reflect and Discuss

➛How can you restructure events like back to school night to be more of a two-way conversation with families?

➛What "good intentions" do you and your school have about getting to know students and families better? Can these interactions be given greater priority or restructuring?