In 1994, Italian soccer great Roberto Baggio stood before a packed Rose Bowl stadium, a mere 12 yards from the goal. His task was simple: Kick the ball into the net, past the Brazilian goalkeeper. Under normal circumstances, it would have been an easy feat. Baggio, in fact, had a nearly perfect record of penalty kicks in his illustrious career.

But these weren't normal circumstances. His teammates had missed their shots in the tiebreaker shootout, so Baggio's kick was now a sudden-death affair. If he missed, his team would lose its four-year quest for the World Cup.

Knowing the Brazilian goalkeeper's propensity to dive left, Baggio aimed for dead center, just above his opponent's head. As predicted, as Baggio contacted the ball, the goalkeeper dived to the left. The ball flew straight—but sailed, agonizingly, over the crossbar (Baggio, 2002). With one errant kick, the Italian superstar lost the World Cup.

Researchers have since discovered that Baggio's miss actually falls into a predictable pattern. When kicking to win—that is, to give their team the lead in a shootout—professional soccer players make 92 percent of their goals. But when kicking not to lose, as Baggio was, they succeed only 62 percent of the time (Jordet & Hartman, 2008).

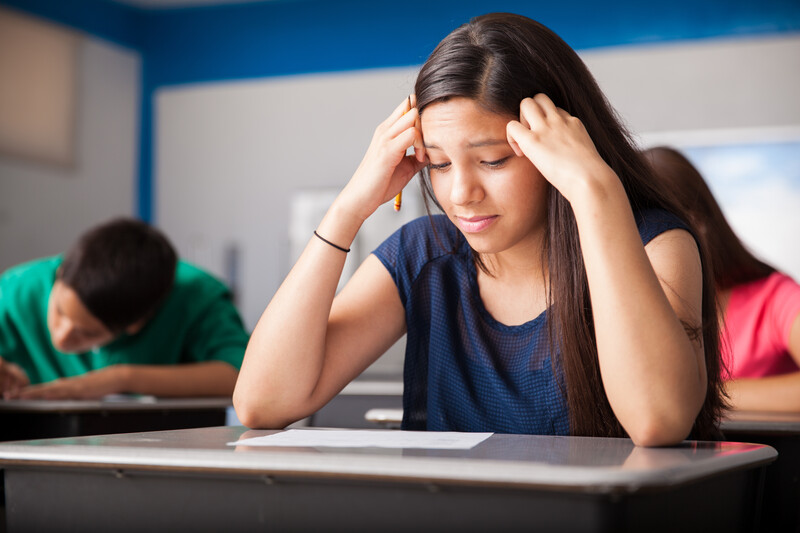

Such stress-related performance dips occur in other environments as well. For example, researchers at Princeton University (Alter, Aronson, Darley, Rodriguez, & Ruble, 2010) gave a math test to a group of undergraduate students who had attended high schools that were underrepresented at that prestigious university. Before the test, the researchers attempted to create feelings of inferiority and "stereotype threat" by reminding the students of their academic backgrounds through a series of demographic questions. For one group of students, the researchers further heightened the threat by framing the test as a measure of IQ; for the other group, they framed it as a brainteaser challenge.

This subtle difference in framing—threat versus challenge—translated into remarkable differences in performance. Students who believed the test was measuring their IQ answered an average of only 72 percent of the questions correctly; students for whom the test was framed as a challenge answered 91 percent correctly.

Framing Problems as Challenges

Bronson and Merryman (2013) catalog a growing body of research that shows how perceived threats affect our brains. When we fear we're being judged or watched, neural activity slows our decision making and our ability to take action. On high alert to avoid mistakes, we actually make more of them; what should come naturally suddenly becomes difficult (which may explain our sudden inability to type or spell correctly when someone is watching us). In contrast, when we have a challenge orientation, our brains relax, enabling us to focus less on what might go wrong and more on the task at hand.

In sports, athletes play looser and better when playing to win instead of playing not to lose. And in organizations, viewing problems as challenges can turn risk aversion and anxiety into openness to new ideas, experimentation, and ingenuity.

Fortunately, research suggests that organization leaders can set the tone that determines whether problems are viewed as threats or as challenges. In a recent study of the management styles of 142 small-business leaders (Wallace, Little, Hill, & Ridge, 2010), researchers found higher performance in companies led by CEOs with a promotion focus (who set ambitious goals and encouraged innovation and new ideas to achieve these goals) than in companies led by CEOs who adopted a prevention focus (who cautiously fixated on preventing errors). A prevention focus, the researchers observed, can be suitable in stable environments where doing business as usual is good enough. But this approach is ill-suited to dynamic environments where new ideas and adaptation are essential.

Leading Schools in Stressful Times

What does all this have to do with school morale? Perhaps a lot.

Consider the results of a recent survey of educators by the MetLife Foundation (Harris Interactive, 2013). Nearly one-half of principals (48 percent) reported being under great stress at least several days a week. A similar percentage of teachers (51 percent) reported feeling great stress several days a week or more, a 15-point increase since 1985, when this indicator was last measured.

Not surprisingly, the highest stress levels are evident in schools that face the greatest external pressure to raise student achievement scores. For these schools, doing business as usual is probably no longer adequate; they likely face what business writers Ron Heifetz and Donald Laurie (1997) labeled adaptive challenges—characterized as "murky challenges with no easy answers" (p. 4). Leadership in these circumstances, according to Heifetz and Laurie, requires encouraging people to solve problems, to be creative, and to take bold action—behaviors that research suggests are in short supply when people operate under threat conditions.

Although ever-increasing external demands to raise student achievement amidst budget cuts are raising stress levels for many educators, school leaders, like company CEOs, may be able to unleash creativity and collective problem-solving by reframing threats as challenges—for example, by converting the fear of school failure into the challenge of helping students succeed. A meta-analysis conducted by Marzano, Waters, and McNulty (2005) found that several promotion-focused behaviors among school leadership are linked to higher levels of student achievement, including (1) serving as a change agent (challenging the status quo and leading efforts that have uncertain outcomes); (2) demonstrating flexibility (being comfortable with major changes and dissent); and (3) being an optimizer (encouraging innovation by portraying a positive attitude about teachers' ability to achieve what may seem to be beyond their grasp). Many of these leadership behaviors, in fact, surfaced as being vitally important when guiding schools through the work needed to accomplish "second-order" changes—akin to the adaptive work described by Heifetz and Laurie.

Playing to Win

When people feel threatened or stressed—like the teachers and principals who responded to the MetLife survey—they are typically reluctant to make decisions, try new approaches, or take bold action. So raising school morale by reframing problems as challenges isn't just a way to make everyone feel good—it's a way to increase the likelihood that your school will score the winning goal.