Students are growing up in a pivotal moment in our history. The pandemic, racial reckoning, climate crisis, school shootings, and other complex issues have underscored for them—and all of us—that there are no easy answers to many of society's challenges. These current times do, however, present rich opportunities for students to become directors of their learning.

Integrating learning experiences in which students lead their learning and engage in social problem solving is easily within the reach of educators. This type of socially engaged instruction can also transform students' hopelessness about difficult times into optimism and action.

Through our work at Rutgers University's Social-Emotional and Character Development Lab, we've been helping schools develop social problem-solving strategies for more than three decades. The lab has developed a project called Students Taking Action Together (STAT) that consists of five research-backed teaching strategies to support students in intentionally rehearsing behaviors in the classroom that are essential for active participation in democracy. (For more information about STAT, see our 2022 ASCD book, Students Taking Action Together: 5 Teaching Techniques to Cultivate SEL, Civic Engagement, and a Healthy Democracy.) One feature of STAT is the problem-solving strategy PLAN that by design empowers students to self-direct both their research into any historical event, current event, or school-based issue and their own engagement in problem-solving when no clear solution is evident. With PLAN, students learn in small groups how to tackle complex social problems. As they practice these skills, students apply the steps of the problem-solving framework to social problems in their daily lives in and out of school.

PLAN's framework has four steps:

Identifying the problem and crafting a description of it.

Listing options to solve the problem and using research to weigh the optimal approaches.

Designing an action plan and considering how it might play out, based on the outcomes of similar historic events.

Noticing successes of the problem-solving process for ongoing evaluation and refinement.

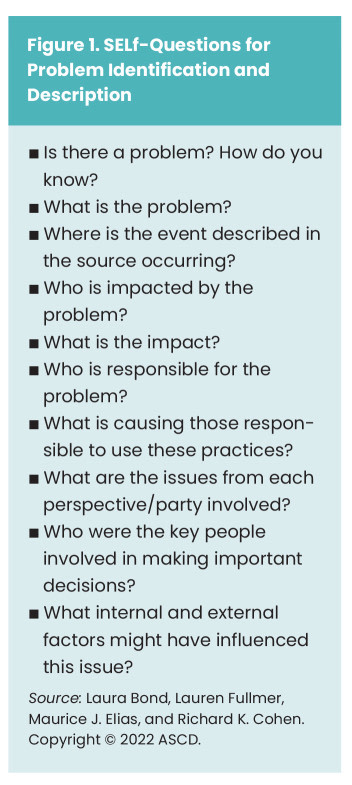

The four steps, along with the power of collaborative learning, provide clear processes for students to reach their goals. Each step includes guiding questions for support and suggestions to help the group determine its course and assess its progress. Such questions, called "SELf-Questions" or "SELf-Q," are questions students ask themselves when engaging in academic learning and social-emotional learning that don't need modification across content or contexts (Cohen et. al, 2021). By adding a focus on social problems connected to emotionally resonant topics of injustice or oppression, PLAN helps to accomplish the main goals of self-directed learning, which are: Enhancing learners' self-determination in their studies, promoting transformational learning, and supporting emancipatory learning and social action (Merriam, Caffarella, & Baumgartner, 2007).

Targeting Critical Thinking

The SELf-Questions serve as a prompt for critical thinking. One example entails teachers asking students in whole-group instruction, "How do you know?" and then challenging students to repeat this question to themselves during guided and independent practice.

Metacognitive questions such as this lay the foundation for the self-directed learning embedded in PLAN. Let's look at how these SELf-Questions work in the PLAN strategy.

Step 1. Create a Problem Description

For more than a decade, the Metuchen School District in New Jersey has been using the metacognitive questions included in PLAN to engage students across all age groups in self-directed research and problem-solving. One social justice lesson that students encounter using STAT focuses on Cesar Chavez, an activist who organized California farm workers to protest for labor protections, civil rights, and public health from the 1960s to the early 1990s.

Working in groups, students begin by examining background sources on Chavez's work, such as speeches, articles, and videos, to develop the knowledge necessary to identify and describe a central problem, such as how marginalized groups can overcome economic and social injustice. Addressing issues of injustice where there is no clear solution can seem tricky, but when students use guided questions such as the ones in Figure 1, they can develop clarity and understanding of the problem.

In the Chavez unit, they may start by asking themselves SELf-Questions such as, What is the problem and why is it a problem? Next, they might ask, How do I know it is a problem? With these questions, students develop the mental habit of both asking and answering questions about the reliability of sources, which is a necessary skill in school and in life (Cohen et al., 2021). Then, in small groups, students ask each other, How can I gather the pertinent information?, which serves as a self-cue to guide the development of their thinking while sifting through information and misinformation.

After researching and investigating the problem from the point of view of various stakeholders, such as farm owners, a local health board, farm workers, consumers, and others, students then come to a consensus on a problem description. Below is an example problem description students might generate:

Wealthy California grape growers' use of pesticides led to increased rates of cancer among farm working communities and their children. The pesticides were even passed on to consumers, and the farm workers saw it was their responsibility to challenge the grape growers' use of pesticides for the health of their community and consumers.

Step 2. Generate a List of Options

In this step, students assume the role of farm labor leaders to both brainstorm potential solutions to the problem and examine the pros and cons of each, based on their research. Students are encouraged to find additional resources on their own as they take ownership of examining potential solutions. This process effectively replicates the experiences of farm worker leaders at the time and illustrates that leaders deal with great uncertainty in their decision making when addressing novel problems.

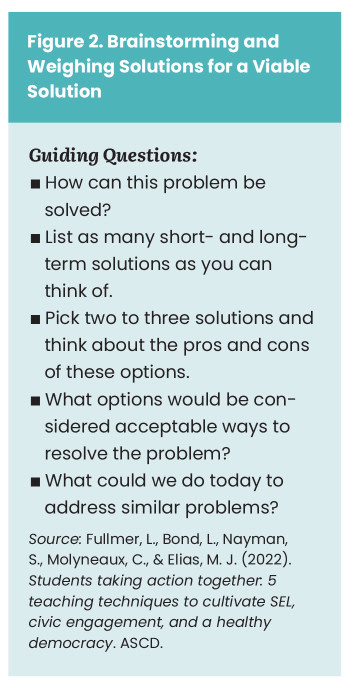

Like Cesar Chavez and his colleagues, the student group must think divergently and also strategically to explore potential solutions. All ideas are welcome during this stage, and the guiding questions in Figure 2 can steer student thinking through this challenging step of PLAN. For example, the students may decide to file a complaint with public health officials, call for a meeting between parties to work out a resolution, rally media attention to the issue to apply pressure on the grape growers, or call for a strike of agricultural workers.

As students discuss and organize their thinking, they prepare for the next step: choosing the most optimal solution. Students exercise the SEL skill of responsible decision making to decide on the best solution by considering which has the fewest negative impacts across all stakeholder groups while still meeting their goals. If, for example, they choose to ask agricultural workers to organize a labor strike because it sends a powerful message to grape growers and slows productivity, they might also note the potential downsides that this action doesn't involve the consumers and would result in a loss of wages for the workers.

The guiding questions empower students to think independently from the teacher. They experience the process of going from problem paralysis to problem identification. They explore various solutions and finally isolate one that is viable. The intentionality of each step of the PLAN strategy scaffolds students' work as they direct their own thinking through each step of democratic problem solving and learning. The gradual release approach embedded in PLAN, combined with metacognitive SELf-Questions, shifts the onus for guiding, prompting, and cueing student thinking from the teacher onto the students themselves.

Step 3. Create an Action Plan

After choosing the most viable solution, students refer to their pro/con analyses and research to craft a SMART goal and an actionable plan, which corresponds to Nezu, Nezu, and D'Zurilla's (2006) "solution plan." The SMART goal steers students to be inclusive of the interests of all stakeholders so they can select the most feasible, yet successful, solution.

For example, after deciding on the solution of organizing a labor strike, students work collaboratively in small groups to develop a step-by-step action plan such as the one below that considers the needs of grape growers, union workers, church activists, lawmakers, and others.

Student Example Action Plan:

Gather workers to discuss the importance and strategy of the strike.

Announce the strike, its rationale, and its purpose.

Coordinate resources to offset the loss of income and groceries.

Develop responses to pressure tactics by growers.

Student groups then present their action plans to a hypothetical audience of farm workers, consumer agencies, or public health experts. This also allows students to practice public communication skills.

Step 4. Evaluate the Action Plan

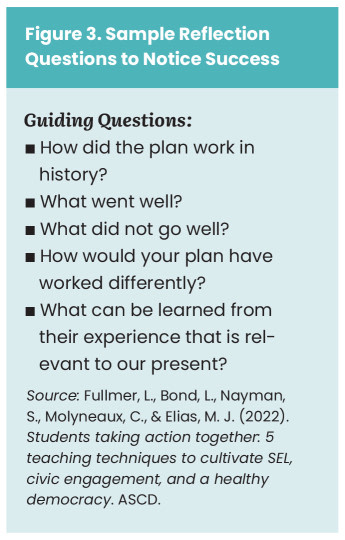

When students reflect on their learning and action plan and notice successes, they begin to see that seemingly insurmountable problems can be addressed and confronted. When they cannot actually implement the action plan (as in the Cesar Chavez lesson, where students are looking at a situation retroactively), students can still theoretically anticipate obstacles and gather evidence to indicate potential degrees of success of their alternative plans.

The teacher can use the SELf-Questions, such as those in Figure 3, to facilitate a whole-class debrief on their action plan, in this case, the organizing of a strike. Then, in small groups, students engage in written reflection, scaffolded by the SELf-Questions, to self-direct their problem solving for novel situations they will encounter in the future at school and beyond school. Below is an example of what students may write upon responding to the reflective questions:

Our plan focused on planning a one-time combined farm workers' strike, in comparison to actual history, where the farm workers organized a labor action over the span of decades. As a part of a broader labor movement, the farm workers called for a national boycott of California table grapes starting in 1984 to ban the use of pesticides. In our action plan, we focused mostly on the leadership's short-term actions and didn't take into account the longer-term actions and pressure tactics that were more successful. As the boycott continued in 1988, Cesar Chavez went on a hunger strike, advancing a continued commitment to the boycott. Even after his death in 1993, the boycott continued up to November of 2000 and was successful in getting the top five toxic pesticides eliminated from use by the grape farm owners. Our group realized a single strike of the farm workers would likely not have lasted as long and been as effective as a boycott. Perhaps this is something we should have considered in our research efforts. Like the limitation of our planned strike, the boycott failed to gain a large following over time.

Through this reflective debriefing, students learn to value their ideas and their capacity to learn new things in new ways. Proposing action plans, considering the views of the various stakeholders who are directly or indirectly implicated, and exploring alternative solutions and the ways they can be feasibly carried out all are essential life skills for every student for a healthy democracy.

Credit: PHOTO BY SOFIA LOPESFourth graders in Sofia Lopes's class at Metuchen School District in New Jersey created a lemonade stand to raise money and food for immigrant families in their local community.

PLAN in Action

The Metuchen School District's strategy includes teacher-driven, open-ended questions directed to the whole class group as well as SELf-Questions posed during small-group and independent work to guide students in critical thinking. Through the use of a consistent strategy across K–12 grade levels, the questioning strategies become internalized by students and drive their own self-directed learning and problem-solving processes.

For example, 4th graders in Ms. Sofia Lopes's social studies class at Campbell Elementary School chose their own subtopics to research for a unit on immigration. Lopes started with the open-ended question, "What were the challenges faced by immigrants on Ellis Island?" Students researched the experience of immigrants who came through Ellis Island and then came together to discuss current problems faced by immigrants new to their own school. Then students worked in groups to ask themselves the SELf-Question, "What can we do to help?" Together they talked about how they could best help immigrant students new to Campbell School acclimate and feel a part of the community.

Students worked in groups to ask themselves the SELf-Question, “What can we do to help?”

Ms. Lopes's class decided that the most viable solution would be to set up a lemonade stand to raise funds and collect food donations for a local food shelter that serves many immigrant families. They worked collaboratively to develop an action plan and split into committees that were each responsible for a specific task. One committee wrote and distributed letters to local businesses requesting donations. Another wrote messages for the school's daily morning and afternoon announcements. The third committee worked with the principal to make a public service video to spread awareness.

The lemonade stand was a resounding success: The students collected more than 1,000 canned goods and raised $400 for the local food shelter. They were also able to visit the shelter and to see its work in action. Ultimately, the students became change agents in their own school community by applying the PLAN strategy.

"It gives them ownership over their work," says Lopes. "They have a choice in what they are learning, and PLAN and SELf-Questions guide them." Just as the steps and structured SELf-Questions are used by students to self-direct their learning and problem solving in the classroom, Metuchen students use those same steps autonomously to self-direct their problem solving in the cafeteria, at recess, or during any social conflicts in their daily lives.

Credit: COURTESY OF METUCHEN SCHOOL DISTRICTSofia Lopes's 4th grade students pose with the food donations they collected for a local food shelter. The students were energized to see their self-directed school project make a difference in the community.

From Guidance to Self-Guided Learning

PLAN's versatility provides opportunities for students to exercise their voices and apply a problem-solving model to take collective social action. PLAN delivers social change and civic experiences in the classroom.

PLAN’s versatility provides opportunities for students to exercise their voices and apply a problem-solving model to take collective social action.

Repeated applications of PLAN are the mechanism through which the strategy yields self-directed learning. As students use PLAN in difficult, ambiguous, and challenging situations, they come to realize and appreciate the benefits of the strategy. PLAN empowers students to confidently tackle problems in their schools, communities, and the wider world with skill. When students believe they can make a positive difference and have an approach to accomplish that, their learning indeed becomes self-directed because it matters to them.

PLAN empowers students to confidently tackle problems in their schools,

communities, and the wider world with skill.

At the heart of today's education is a moral obligation to deliver self-directed learning experiences so students have hope and the skills to envision and make changes. PLAN offers a hopeful way to fulfill the promise echoed in James Baldwin's famous 1962 essay: "Not everything can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced."

Reflect & Discuss

➛ What is the value of teaching students about complex social issues that have no certain solution? What are the challenges?

➛ Is the PLAN method applicable to your own teaching? Why or why not?

➛ What are two or three Self-Questions that would be helpful to ask your students?

Students Taking Action Together

How to intentionally rehearse democratic behaviors in the classroom to prepare young people for life in a democracy.