Today's schools need to prepare a generation of learners for a world that is constantly changing. Knowledge is expanding exponentially in many fields. New and often disruptive technologies, such as artificial intelligence, CRISPR, and the metaverse, continue to shape our environment, presenting novel challenges and opportunities.

Accordingly, a modern education should involve more than simply having students acquire a fixed body of knowledge presented by teachers and texts. To prepare students for a dynamic, unpredictable future, educators must help them develop an essential life-long skill—the capacity to independently direct their own learning, in school and beyond. To do so, we recommend schools and districts take the following four actions:

Prioritize self-directed learning as a fundamental goal of schooling.

Identify the key skills associated with self-directed learning and map them out across grade levels.

Explicitly teach and reinforce these skills.

Provide students with regular opportunities to self-direct their learning.

1. Prioritize Self-Directed Learning

The skills required for self-directed learning are unlikely to develop on their own. Nor will these skills fully blossom from the actions of one or two teachers working alone. Helping learners achieve effective self-direction requires a comprehensive approach that systematically develops key skills across grades and disciplines.

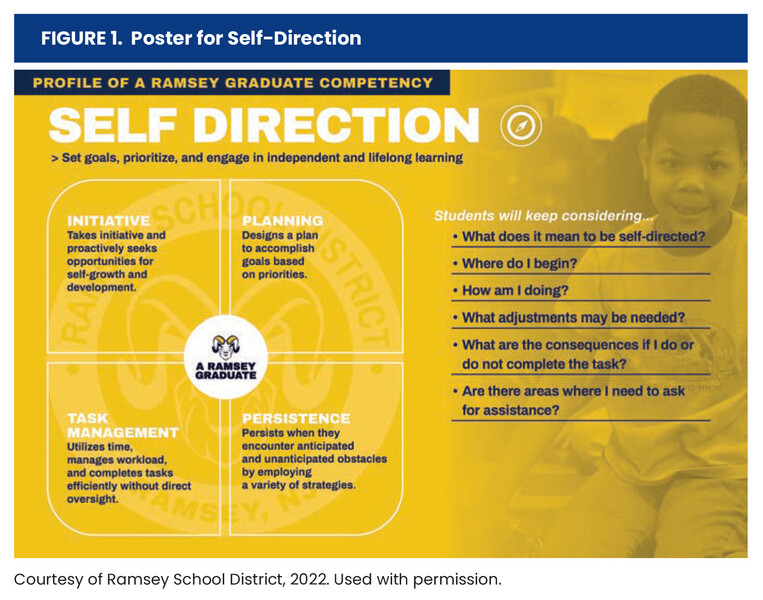

Here's one example of such a coordinated approach: The Ramsey School District in New Jersey directed staff and community members to formulate a profile of a graduate that articulated desired competencies students should exhibit as a result of their preK–12 school experiences. Self-direction was one of these key competencies. To signal their importance, the district designed posters highlighting each of the competencies and displayed them prominently throughout schools. The poster in Figure 1 includes a description of four elements of self-direction and a set of associated essential questions meant to guide the development of this competency across grades and subject areas.

Of course, the creation of a poster is insufficient to ensure that all students develop the capacity for self-directed learning. Such an important competency must be cultivated deliberately. Let's examine how schools can do just that.

2. Identify Key Skills of Self-Directed Learning

The ability to direct one's learning involves a constellation of skills, including setting learning goals, developing a learning plan, making needed adjustments, and reflecting on the learning results. Effective self-directed learning also requires perseverance in the face of obstacles. These skills and habits of mind can, and should, be cultivated by design.

Effective self-directed learning requires taking initiative and persevering in the face of obstacles. These skills and habits of mind can, and should, be cultivated by design.

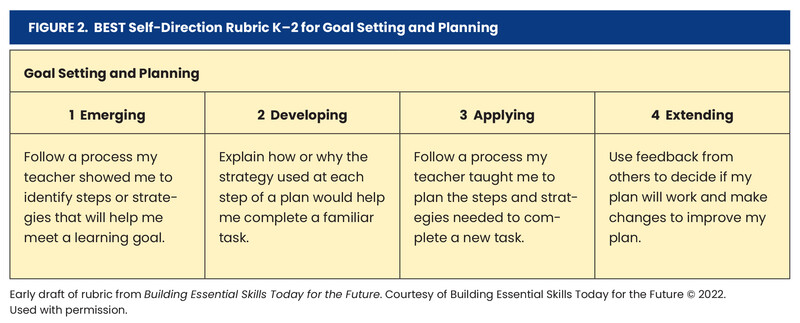

That design begins with schools and districts clearly identifying the key self-directed learning skills they aim to foster in their students. A great example of targeting and mapping self-directed learning skills is the Self-Direction ToolKit developed by the Building Essential Skill Today (BEST) research-practice partnership (BEST, 2020). The toolkit includes a set of rubrics that identify key independent learning skills arranged developmentally for grades K–2, 3–5, 6–8, and 9–12. In addition to highlighting specific skills, the rubrics describe proficiency levels to guide assessment by teachers and self-assessment by students. This kind of resource not only makes it easier for teachers to focus on self-directed learning generally, it enables schools to track student progress over time.

3. Teach Self-Directed Learning Skills Explicitly

Research recommends a direct instruction approach to the development of self-directed learning that calls for teachers to:

Map out key self-directed learning skills to teach explicitly.

Break down complex skills into their components.

Provide strategies and scaffolding tools to support learners as they acquire skills (Rosenshine, 2012).

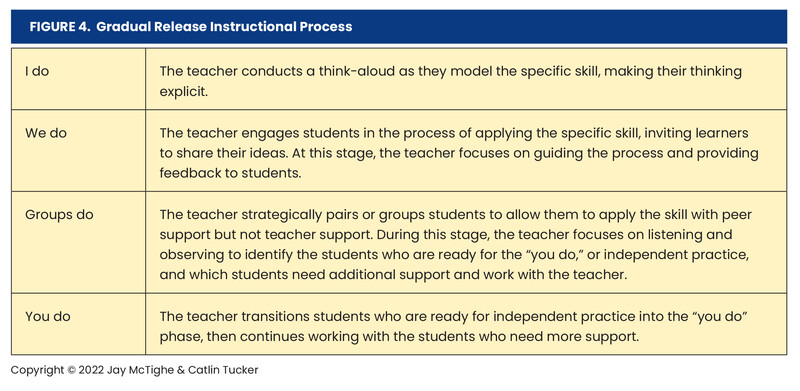

It's best to model independent learning skills and allow students to practice them using a gradual release of responsibility approach.

Map out key skills to teach explicitly.

Once schools have identified the skills they want to target, they need to articulate what the development of each skill looks like by designing a set of rubrics across developmental levels. Well-developed rubrics provide clear and age-appropriate learning targets, support focused instruction, and guide assessment, including self-assessment by learners. In Figure 2, we see a rubric developed by BEST that focuses on goal setting and planning in grades K–2. This rubric clearly identifies the stages of mastery and describes each stage with clear, student-friendly language.

Break down complex skills into their components.

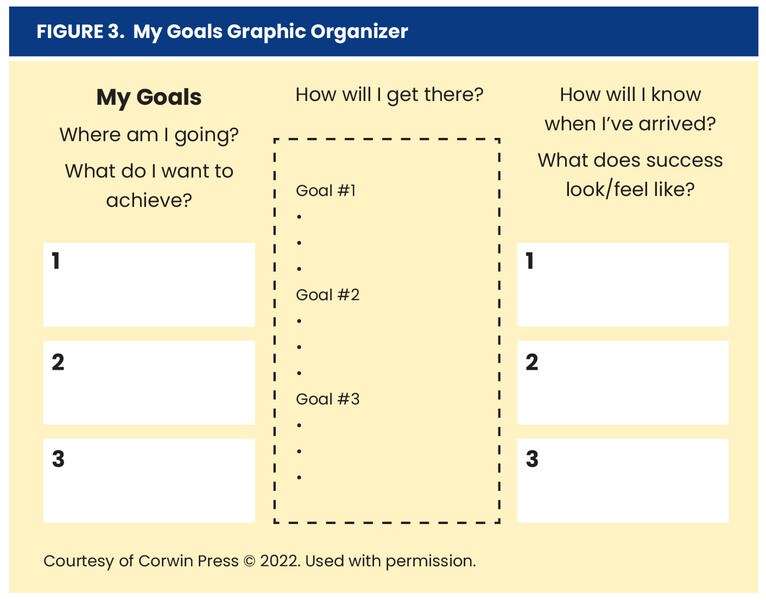

Each self-directed learning skill needs to be deconstructed into "teachable" parts. For example, goal setting and planning can be broken down into: setting specific and measurable goals, articulating the steps needed to attain the goal, identifying needed resources and tools, seeking feedback, and monitoring progress along the way.

Teachers can support students by setting objectives appropriate to their age and directly teaching the targeted skills. For example, younger students benefit from a guided goal-setting lesson with the teacher in a small-group setting, while middle school students can use a graphic organizer, like the one pictured in Figure 3. High school students can use more sophisticated aids, such as a SMART goal-setting tool and time-management forms to guide their independent work.

Once students gain confidence in setting meaningful goals and planning their actions, they should be encouraged to regularly monitor and reflect on their progress. Here are some sample prompts:

How much progress have I made toward my goal(s)?

Might I need to adjust a particular goal?

Which actions, strategies, tools, and feedback have been most helpful?

What obstacles or challenges have I encountered? How did I respond to them?

What will I do differently next time I work toward a goal?

Teachers need to model self-directed learning skills and support students as they practice them. Teachers may use a simple "I do, we do, groups do, you do" format (as outlined in Figure 4 on p. 61) to gradually release responsibility to learners (Kilbane & Milman, 2014; Tucker, 2022).

4. Provide Opportunities for Self-Direction

It is unlikely that students will become better at self-directing their learning if they have limited opportunities to practice. Sadly, the academic lives of many learners are completely directed by teachers. Always being told what to do and how to do it undercuts self-direction and can lead to students becoming increasingly passive and disengaged. Indeed, many secondary teachers have observed students who develop a "minimum compliance" mentality, evidenced by queries and complaints such as: "How many words do you want?" "I don't know what to do," or "How many points is this worth?"

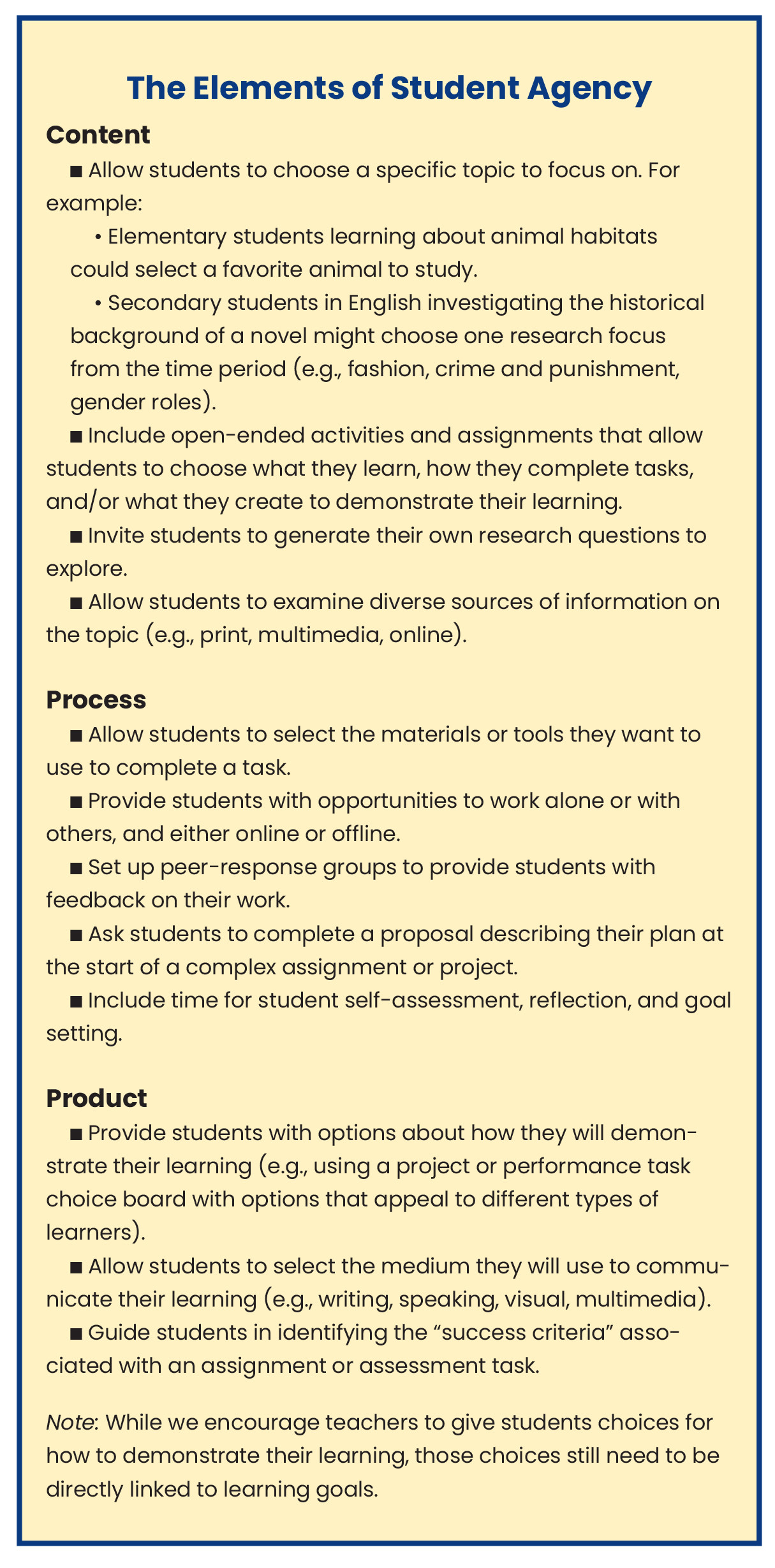

To foster confident and capable self-directed learners, teachers should prioritize student agency in their classrooms by creating opportunities for students to make decisions about their learning. We recommend that teachers think about student agency in terms of content (what they learn), process (how they learn), and product (how they demonstrate their learning). See "The Elements of Student Agency" (on p. 63) for strategies to help students make agency happen.

Two Strategies for Student Agency

Teachers may initially feel overwhelmed by the prospect of giving students agency over content, process, and product, so it is important to think big but start small. It can be helpful for teachers to use the "Would You Rather …?" strategy by presenting two options for students to choose from. For example, teachers may offer students the option to listen to a podcast or watch a video to learn about a topic or take traditional notes or draw sketch notes as they read.

Offering "Would You Rather …?" choices requires minimal planning time, but can enhance student motivation, engagement, and academic performance (Anderson et al., 2019). This simple strategy helps students get comfortable making decisions about their learning and can be especially beneficial for learners who feel overwhelmed when deciding between multiple options.

To get started designing for self-directed learning, teachers can also use the GRASPS protocol. GRASPS is an acronym used to develop a performance task or project (McTighe, Doubet, & Carbaugh, 2020). The acronym stands for: a real-world goal; a meaningful role for the student; a target audience(s); an authentic (or simulated) situation that involves "real-world" application; culminating products and/or performances that provide evidence of learning; and success criteria for assessing student work.

The Role, Audience, and Product/Performance elements of GRASPS can be varied to provide structured opportunities for student choice. For example, students could choose between playing the "role" of historian, book critic, or opinion writer in a given task or project.

The Audience and Product/Performance variables often intersect to allow for differentiation and student choice. For example, 6th grade students learning expository writing could draft a picture book for primary grade children, a news article for middle school students, or a policy paper for adults. For a math, science, or economics project involving statistical analysis, students may have the option of developing an infographic or a slide show presentation.

But when students produce varying products and performances, won't a teacher need to have multiple rubrics to evaluate these various options? Our answer is a qualified "no." If the goal of GRASPS is the same, then the success criteria should be the same. Thus, a single rubric can and should focus on the key qualities embedded in the goal rather than on the surface features of a particular product or performance. For example, a performance task involving argumentation would include success criteria such as:

A claim (or position) is clearly stated.

Sound reasons are presented to support the claim.

Appropriate evidence is cited.

Opposing claims and reasons are effectively rebutted.

The language and examples are appropriate for the target audience.

Regardless of whether students produced a position paper, presented an oral argument, or completed some other assignment, their work would be judged by the same success criteria.

Shifting Teacher and Student Roles

In classrooms that prioritize self-directed learning skills, students shift from passive observers to active agents making decisions about their learning. Teachers shift from being the expert at the front of the room orchestrating the lesson to spending more time facilitating and coaching, offering feedback, and providing support.

In classrooms that prioritize self-directed learning skills, students shift from passive observers to active agents making decisions about their learning.

As students develop confidence in their ability to direct their own learning, they can assume more responsibility for tasks that have traditionally fallen on the teacher, such as planning, feedback, assessment, and communicating progress with families. This increased autonomy can motivate learners and free teachers to spend more time and energy supporting their students. Not only do these shifts develop more dynamic learning communities, they also provide students the skills to continue learning independently long after they leave school. In a world where knowledge and technology change at staggering speeds, today's students need to be nimble and able to thrive in a future that will look very different from their reality today.

Copyright © 2022 Jay McTighe & Catlin Tucker