It has been a volatile past few years.

Amidst a global pandemic, national protests for Black lives emerged following the murder of George Floyd in May 2020. One month later, every nonfiction book on the New York Times's best-seller list was about antiracism (Grady, 2020), and many organizations and businesses around the country released anti-Black-racism pledges and statements. Then, on January 6, 2021, we watched an example of white supremacy at work as the U.S. Capitol was stormed, representing violent threats against our democracy. Anti-critical-race-theory movements infiltrated school systems in the following months, leading to curricular censorship bills and in some counties, the harassment of educators, teacher-librarians, and school officials who strived to promote equitable practices (Bradley, 2021). Books that were widely proclaimed when antiracism was trending have now faced petitions to be banned from libraries and school reading lists.

Our educational institutions have been deeply affected by these cultural and political shifts and by a history of systemic racism and government-sanctioned laws that have failed to recognize the full humanity of all people. This has made the teaching profession challenging and, at times, a source of weariness. This is above all a time when education leaders must rise to the challenge of protecting the interests of underserved students and community members. As educators grapple with the happenings of the world and their implications for educational settings, I believe we should be guided by the following principles:

What we teach young people and how we teach matters. The learning spaces and conditions we co-construct with students today will influence the steps they take for a just world tomorrow.

We cannot allow our ideologies to limit us from embracing multiple perspectives or to justify the inhumanity and discrimination that are perpetuated throughout society. We must examine the beliefs we hold that shape educational systems.

We can use our power to create the responsive systems and affirming spaces students, educators, and families deserve.

Education leaders must ensure that their learning spaces center the humanity of students—their identities, histories, and lived experiences.

This is not easy work, but it is critical work. Education leaders must ensure that their learning spaces center the humanity of students—their identities, histories, and lived experiences—and make them feel emotionally safe. We can do this through three concepts I have found helpful in my own work: mirror work, systems work, and equity-focused leadership (Buchanan-Rivera, 2022). The work of transforming systems requires educators to consider the environmental conditions (such as interpersonal relationships, curriculum, physical classroom environments, physical safety, pedagogical approaches, and more) that may harm or elevate students' academic and social growth. This work does not happen by chance—it happens by reflecting on our own values and beliefs and the way we mirror those within our school systems. We cannot help youth understand each other when we don't understand ourselves and how we've been shaped to view the world.

These three practices allow us to learn more about our strengths, areas of growth, and the origins of beliefs that influence how we operate in society and educational spaces. They can push us to question injustice when we see it, to use our voice and recognize our power. And they can show us how to make our dreams, hopes, and imaginations align with our individual and collective actions. We can maintain these values through conflict and difficulties and find power in community to combat the persistent, often strategic, political challenges that harm schools and outcomes for young people.

Mirror Work: Aligning Beliefs to Action

It took many years of advocacy work for high school juniors at Boulder Valley School District in Colorado to get approval for an ethnic studies course that includes texts representing different cultures, identities, and history—even though their district highlights core values of diversity appreciation, equity, and inclusion on its website (Bounds, 2022). In other schools, community groups often steeped in bigotry protest inclusive curriculum at board meetings until leaders feel pressured to alter instructional experiences or materials.

What message does it send to communities, educators, and students—particularly minoritized groups—when values of inclusion are promoted and posted on school websites, yet exclusionary practices are deliberately implemented or, at times, mandated? Youth cannot afford to be taught in schools with such misalignment between values and actions.

This misalignment is typically a reflection of the struggles of leaders to cultivate and foster systems for equity. If leaders are not committed to ongoing cultural work, lack the knowledge to educate staff and stakeholders of the "why" behind equitable practices, or struggle to navigate conflict, then core values of inclusionary work may only live in written-word form, such as vision statements, social media posts, websites, or taglines.

Erica Buchanan-Rivera guides teachers and administrators through “mirror work,” reflecting on how their experiences might hinder or support the advancement of students, at the Teach Indy Conference in February 2023. Photo courtesy of Chapital Photography.

As a DEI practitioner in a district-level position, I often challenge educators to unpack what they are projecting into educational spaces due to their lived experiences. Many principals and directors have shared their challenges to lead systems for equity. Some leaders have discussed their encounters with resistance within the workplace, community pushback, or their lack of understanding of how to navigate critical conversations about race, gender, or other topics. In relation to racial equity efforts, I have worked with white administrators who do not feel equipped or confident to address discussions about institutional racism, and I have partnered with administrators of color who struggle to hold discussions about race due to either their socialization in systems of whiteness or fear of racial microaggressions amid a predominantly white teaching staff.

Leading for equity means we make our beliefs about justice transparent in decision making and interactions with others. We strengthen our ability to have critical conversations about equity when we commit to learning that enhances our worldview and live out beliefs about justice in our everyday lives. If leaders do not practice what they learn from diverse educational spaces, human connections, or opportunities that center inclusionary or anti-racist work, then it may be difficult for them to model equitable practices and align actions to beliefs. We also cannot let fear serve as a barrier to justice-centered work when our students' well-being is on the line.

When I ask leaders to share how they deepen their understandings of equity, they often point to experiences that center the workplace—attending conferences, creating a DEI-related committee, or reading a required text. If I push and ask, "What do you do outside the context of work for your well-being, healing, or humanity to walk toward a path of justice?", it's harder for them to generate a response.

Leading for equity is not a professional development checkbox; it should be part of one's being and obligation when working in community with others. This work is not a moment, but rather a movement. We cannot enter our workspaces and strive to center the humanity of students and colleagues and then forget about this work as soon as we walk out of the school building. We must have an internal drive and commitment to learn and unlearn, to examine our own circles and assess whether we are surrounded by individuals who will inspire us to be better versions of ourselves.

Lisa Delpit reminds us that we do not really "see through our eyes and ears, but through our beliefs" (2006, p. 46). Ideologies influence how we see one's humanity and how we respond to others. The following questions can support leaders' mirror work to ensure that beliefs and actions align in efforts to construct systems that affirm the identities of students:

How does the work of advancing equity show up in my work?

How does the work of advancing equity, dismantling racism, and creating inclusive, affirming environments show up in my everyday life?

How am I using my power to ensure that each student, family, and colleague feels a sense of belonging?

How am I using my power to create systems and spaces where all students can thrive? (Buchanan-Rivera, 2022)

Systems are driven by human work, and there will be times when we fall short and experience a misalignment between our beliefs and actions. When this happens, we need people in our lives who can serve as critical thought partners, point out these inconsistencies, and provide loving accountability.

Systems Work: Creating Just Conditions

While mirror work focuses on a critical examination of self and the beliefs that guide our actions, systems work focuses on the conditions needed for inclusive, affirming, and responsive educational spaces—often leading to collective approaches, since everyone plays a part in maintaining and sustaining a cohesive community. There are many external factors that influence the course of progress in school systems, but leaders should be careful to examine the factors within their school system that they can control. It can be tempting to blame outside factors rather than look within an institution and admit that what you are doing is not working. It's even harder to come to the realization that maybe you are part of the problem.

For example, families who don't show up for parent-teacher conferences or their child's band concerts are often labeled as "uninvolved" or "irresponsible." Students who don't do well on standardized tests are blamed as being unmotivated or unteachable. Deficit ideologies breed these types of categorizations. It is easier to accuse another individual or community than to reflect on what is failing in the system and how our power can be part of the solution.

School leaders who are systems-focused seek to create the conditions that lead to just, anti-racist, and equitable outcomes.

In his book Peace Is in Every Step, Vietnamese Buddhist monk Thich Nhat Hahn wrote, "If you plant lettuce, and it does not grow well, you don't blame the lettuce" (1991). Instead, you assess the reasons why the plant is not growing and examine the conditions surrounding its inability to thrive. In the same way, school leaders who are systems-focused seek to create the conditions that lead to just, anti-racist, and equitable outcomes. We do not label parents as being uninvolved, but study the conditions of school spaces and question whether our environments make certain people feel unwelcome. We do not initially blame students and their caregivers for poor achievement outcomes, but examine the ways curricular materials, interpersonal relationships (among students, caregivers, or staff), communication practices, and school culture impact their learning.

Systems work compels educators to engage in activism. When we recognize that systems do not benefit all students, we do something about it. We organize in collaborative spaces to devise deliberate actions. We question literacy practices that are not responsive to the needs of students of color. We inquire into whether school-based decisions consider the well-being of employees and students. We develop areas of focus that include metrics to evaluate progress. We push and make noise for things that matter.

The following reflective questions are helpful to consider when examining systems for the conditions they create for learning and equitable outcomes:

How do I demonstrate care for all families, caregivers, and colleagues, particularly individuals who have contextual experiences that are different from my own?

How am I disrupting identity threats or stereotypes and creating conditions where students feel valued?

What safety nets are established for students in need of academic or social-emotional support? Are the strategies meeting the individualized needs of learners or do they serve as a checkbox?

What opportunities are offered for students or colleagues to learn about each other and process the world around them for growth and human development?

How does curriculum or instructional practices honor the identities, histories, and experiences of all learners?

Equity-Focused Leadership

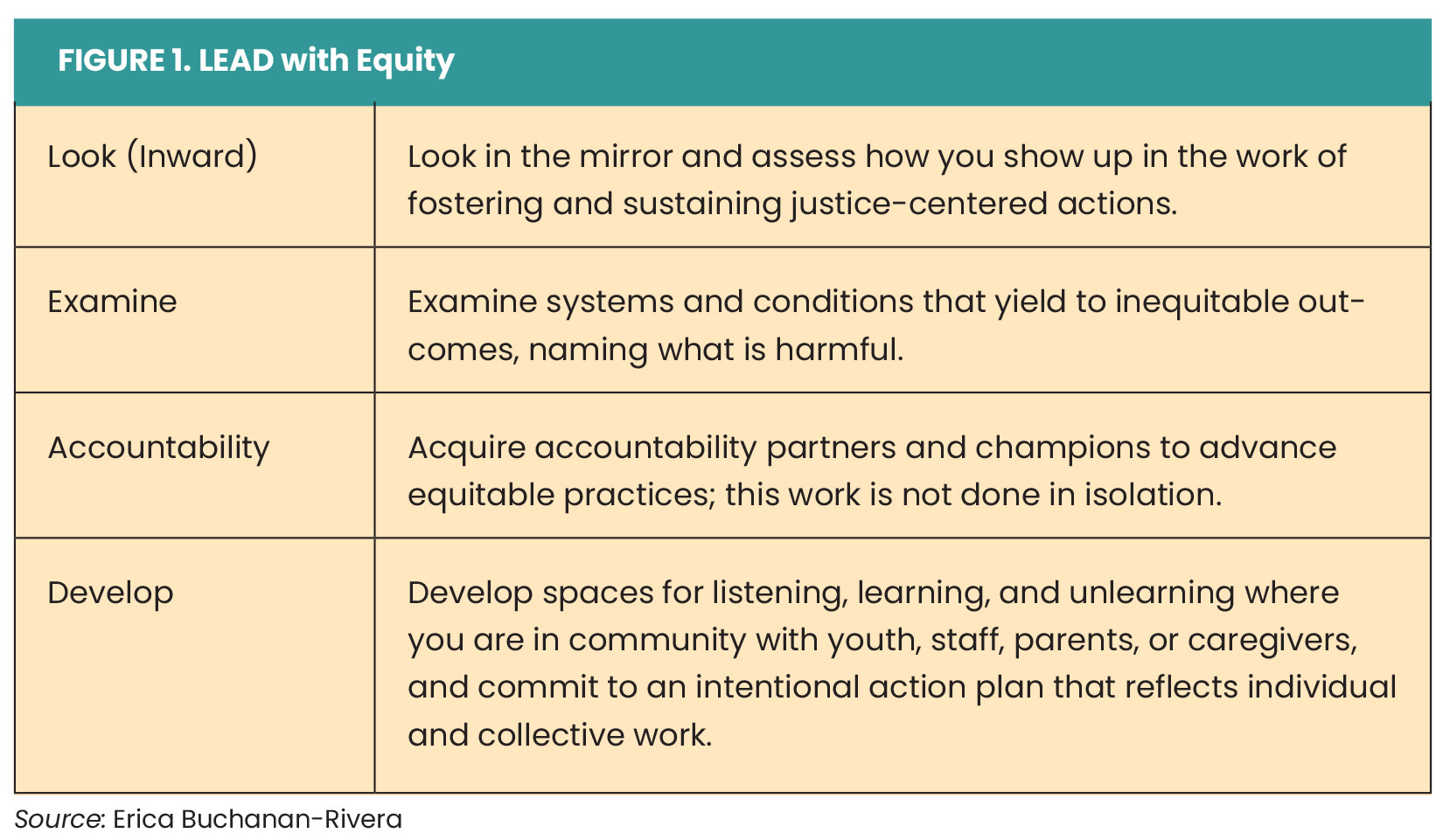

Figure 1 shows guidelines I've created to help people think about how they can lead for equity. In addition to looking within oneself and assessing school systems, equity-focused leadership requires listening to the needs of our communities and considering our approaches to engaging staff, students, and families in collective efforts. Being in community with others means that we work to build authentic connections.

Often, educators hear about the value of building relationships, but those conversations do not typically delve into the "how" of making connections and facilitating mindful practices. Leaders must create spaces for learning and unlearning, processing the needs and perspectives of communities who may have critiques of educational systems. Rather than being defensive (and rhetorically generating a list of things that are going well to protect ourselves), we must be open to narratives of what is not effective within institutions—especially from the perspectives of students.

We exist in an era of truth decay and censorship, where political groups co-opt equity-related terms for their own agendas. It is vital for school practitioners to communicate the purpose of their efforts toward equity and show how these efforts affect student outcomes. If we are not transparent about the purpose and journey of collective work to improve the experiences of students, others in our political climate will certainly create their own narratives and fill in the gaps.

As leaders, we need to spend time celebrating the small and big wins and educate our communities on promising strategies to change outcomes.

Although the effort to improve education systems is an ongoing process, I know there are examples of schools and educators who are doing intentional, impactful work that is being felt by students. As leaders, we need to spend time celebrating the small and big wins and educate our communities on promising strategies to change outcomes—naming what is working and where the barriers are.

I have worked in districts with strong community coalitions. The organizations consisted of parents, educators, and partners who worked collectively to support schools. As a DEI director, I have educated coalition members on the systems work happening in schools and areas where school leaders needed their support. Last year, during the wave of anti-CRT movements in Indiana, the community coalition in my school district worked to dispel misinformation on Critical Race Theory, wrote a public statement in partnership with other school-based organizations that outlined why conversations about race and history matter, and testified against an anti-CRT bill, which ultimately did not pass, in 2022 (Ferlazzo, 2022). There is power in community.

A Risk Worth Taking

The work of creating just systems is human work. It is not an easy task and comes with risks. But we also must own our stories and make the work of advancing equity transparent. You do not have to wait for anyone's permission or invitation to mobilize, interrupt harmful practices, or show up for someone experiencing marginalization. We can lead fiercely, acknowledge what sabotages joy, and focus on our collective power to co-construct positive educational experiences. We can remain systems-focused despite adversities the world reveals and maintain our light during times of uncertainty, with a clear vision that centers humanity.