Most teachers are familiar with the argument that precious instructional time should not be spent teaching specific content when everything can be "Googled." After all, we have no idea what content is going to be relevant to our students in the future. Instead, teaching time is better spent focused on 21st century skills like critical thinking, creativity, collaboration, and innovation. In many educator circles, it is almost heretical to question these assumptions, and if you do, you run the risk of being labeled "old school."

But there is a problem with that thinking. When I was first starting my graduate studies in history, a professor of mine had the unfortunate task of privately taking me aside to inform me that I needed to broaden my inventory of knowledge. When it came to making connections between ideas, evaluating assertions, questioning assumptions, formulating original ideas, or identifying significance, he observed, my strong critical-thinking skills were not going to be enough to offset my inadequate body of historical knowledge.

Without a solid foundation of core knowledge stored in one's own memory, a student cannot move nimbly through the world of ideas, building on some and rejecting others. Additionally, students require background knowledge to decipher texts and understand references. This professor's words were painful at the time, but they were also true. Most important, the necessity of solid background knowledge he was talking about is relevant to learning at all ages—and is especially important for reading proficiency.

The More You Know …

When it comes to reading, research shows that background knowledge significantly influences basic comprehension, even in our youngest learners (Recht & Leslie, 1988). In fact, cognitive scientist Daniel Willingham (2009) makes the argument that "teaching content is teaching reading."

Thanks to a flurry of recent writing about this issue connected to Natalie Wexler's book The Knowledge Gap (2019), an important conversation about the role of background knowledge seems to have been rekindled. In her book, Wexler argues that students need both skills and content to make meaning and to think creatively and critically. Skills are important, but should not be taught in isolation, she notes. Rather they should be taught in the context of subject-specific content.

Perhaps most critically, Wexler observes that the students most hurt by the movement away from instruction based on content knowledge and retention are students from less advantaged backgrounds. Although all families provide their children with valuable skills in communication and navigating life challenges, poorer students may not benefit as much as wealthier students do from frequent conversational references outside of school to ideas and vocabulary that are relevant to academic work, or enjoy the same enrichment opportunities—like visits to museums and after-school classes.

Wexler also illustrates how knowledge builds on knowledge, like a snowball effect. A strong foundation, such as solid core content knowledge, makes it easier to build layers of learning, while a weak foundation hinders the formation of those layers—a problem that compounds over time. This phenomenon is often referred to as "The Matthew Effect" (in reference to the "Parable of the Talents" in the Gospel of Matthew) (Stanovich, 1986).

"The Matthew Effect" also applies to decoding skills, which Wexler describes as key to students' ability to build knowledge. While research hasn't illuminated any benefit to teaching reading comprehension skills in isolation, Wexler argues that decoding needs to be taught and practiced as a specific set of skills, pointing to studies showing that most kids benefit from sequenced, explicit, code-based instruction to learn how to decode—and students with dyslexia desperately need it. Experts estimate that only about half of all kids will learn to read with broad instruction that includes just a bit of phonics (and a very small number, about five percent, may learn to read no matter what kind of instruction occurs) (Young, 2018).

The time investment in decoding instruction is worth it; after all, this phase is our best chance to build strong readers who will be able to access content throughout their lives. Students who are poor decoders predictably become ineffective, reluctant readers. Throughout life, they'll likely read less than those who decode with automaticity, giving them less chances to both strengthen their reading skills and gain background knowledge.

Content Questions

The idea that information is just as usable whether it's stored online or in one's memory is an appealing and convenient concept for teachers. I wish it were true. I have yet to meet a group of teachers who think they have enough time to meet their instructional goals. Letting go of content-coverage goals would free up precious instructional time. Teaching content also brings in thorny questions. With the proliferation of information available, how does one decide what content is most essential? Who decides what makes that list? How do we correct for cultural biases to create curriculum that doesn't perpetuate them? These questions and tensions alone make many teachers want to pivot away from the pressures of content instruction.

But although teaching content can raise challenging issues, we can't cheat students of this deeper knowledge that will improve their reading lives. The good news is, resources exist to help teachers determine what kinds of information should be covered at each grade level. One source Wexler suggests is The Core Knowledge Sequence, which offers a list of topics teachers should cover from kindergarten through 8th grade. The creators curated the list after soliciting input from university professors, parents, teachers, and a multicultural committee. Deeper Reading

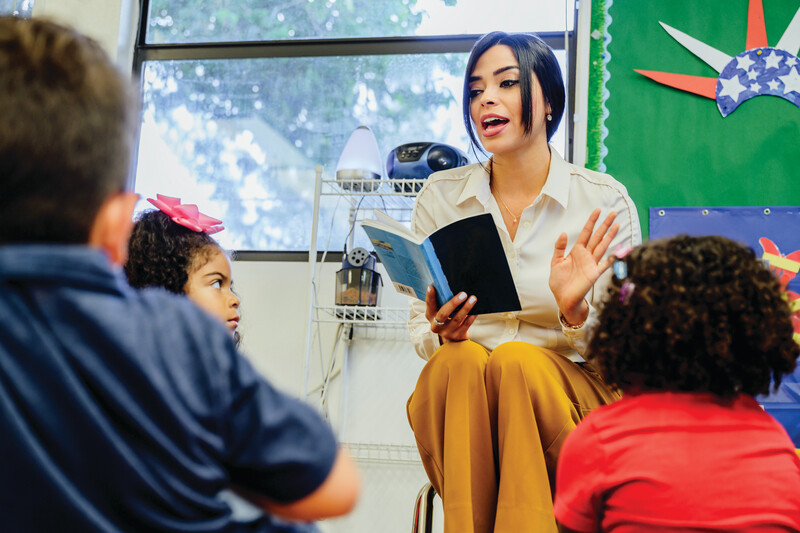

Of course, there are tradeoffs involved in choosing instruction centered on content versus choosing instruction focused on specific reading skills. But these focuses don't have to be mutually exclusive. In the early years, exposure to science and social studies concepts and vocabulary doesn't have to be limited by a child's reading ability. Early reading instruction can be supplemented with science and social studies content, delivered through a variety of media and read-alouds, even before students are able to decode most content-area reading on their own (Adams, 2010/2011).

Tensions and tradeoffs around whether to spend time with explicit reading instruction or with content instruction continue in upper elementary grades. In fact, they become more complex as a widening range of reading abilities threatens to leave some students behind in accessing grade-level subject area content. But the two areas can be addressed simultaneously.

In our 5th grade classes at Marin Country Day School, my colleagues and I use teacher read-alouds and assign whole-class texts to deliver content. During class discussions, students have opportunities to practice reading comprehension skills and unpack new vocabulary. For example, in our study of America's journey from colony to country, we use historical fiction like Elisa Carbone's Blood on the River (2010) and Susan Cooper's Ghost Hawk (2013) to introduce the diverse motivations behind early European colonization of North America and the cultural clashes that ensued. Later, as we study the early role of slavery in our country and the contradictions that it presented as the colonists formulated their arguments for independence from England, we read Laurie Halse Anderson's historical novel Chains (2010). I read much of the texts aloud to the class (as they read along in their own texts), frequently pausing to unpack vocabulary and explain and discuss historical references. Supplementary lessons also support these topics.

It's important to support students with reading struggles in this kind of combined content-area and literacy work. For required independent reading of class historical fiction novels, I lean on audiobooks and text-to-speech assistive-technology, like Learning Ally and Bookshare, to support and include students who have reading challenges like dyslexia. These assistive-tech tools use new audio technologies that read text aloud, using human or synthetic voices, simultaneously highlighting the words being read on a screen. This help students strengthen their reading skills while reading grade-level content.

I don't think teachers ever need to apologize to their students for the mental nutrition supplied by content instruction. In truth, social studies and science are often my students' favorite subjects. Studying subject-area content sparks curiosity and empowers students as learners. During their end-of-year reflections, many students, if not most, name specific units of study (like American government, local ecosystems, or a class novel) as a learning highlight of their school year.

Valuing Shared and Independent Reading

Class texts are important to teaching content, but if we choose all the books for our students, they will be less likely to develop authentic, engaged personal reading habits. If we want to nurture passionate, independent readers while also encouraging the development of a diverse range of background knowledge, educators need to make time for independent reading. In my class, read-alouds, whole-class texts, and independent reading all compete for a share of limited instructional time, and I do my best to give adequate time to each. According to the 1996 National Assessment of Educational Progress, the amount of reading "for fun" outside of school directly correlates to academic achievement. Other studies demonstrate that there's no better way to increase vocabulary than independent reading (Watkins & Edwards, 1992).

To make room for independent reading, I limit other homework. Reading is typically students' only "homework." Choosing their own books works wonders to help them form a positive relationship to reading. In response to my students' urging, I also sneak independent reading time into the school day every chance I get. As part of our classroom reading culture, students take agency over maintaining our classroom library and enthusiastically participate in frequent bookshares and discussions about what they are reading. Sharing their positive experiences with chosen books is contagious. It feeds and expands their classmates' independent reading lives.

The instructional tensions and trade-offs related to content instruction are real. I don't profess to have the perfect formula, and other teachers may argue with the portions of my reading instruction recipe. However, since possessing a strong knowledge base is essential to a student's ability to make meaning, it seems clear that building this base should not be left to our students' home lives, especially when those home lives vary widely. Schools have a responsibility to build students' core knowledge.

Given the research about how important foundational knowledge is to nurturing strong readers and thinkers, it is time to have some important, albeit complex, conversations about how to support content study in our elementary classrooms. Google just isn't enough.