Leaving a keynote feeling inspired isn't the same as leaving with research-based, actionable information that can add to students' outcomes.

There's a book by Chip and Dan Heath I read some years back: Made to Stick. I remember one story from the book, in particular, that changed the way I operate professionally. The authors detailed a key factor in Southwest Airlines' success in dominating a sizeable share of the flying market. In short, the airline planted a stake in the ground, or sky as it were, as "THE low-cost airline." They don't provide gourmet snacks or luxury onboard experiences, for example, because those would compete with their purpose. All of their decisions followed that purpose.

Making professional learning experiences stick in the long run assumes that the purpose of the PD is to implement some idea or practice in order to change student outcomes. Sure, it would be nice if the experience were entertaining, but leaving a professional learning experience having been entertained is not the measure of an "excellent" professional learning experience. Funny jokes, engaging activities, and stories that tug at the heartstrings enhance and help us consume meaningful content, but they aren't a replacement for the content.

Have you ever left a professional learning experience with an amazing presenter feeling warm and fuzzy—but then realized that there was no new actionable information? Leaving a keynote feeling inspired isn't the same as leaving with research-based, actionable information that can add to students' outcomes. Leaders have the responsibility to respond to teachers' call for more meaningful, "meaty" professional learning that responds to the needs teachers themselves identify.

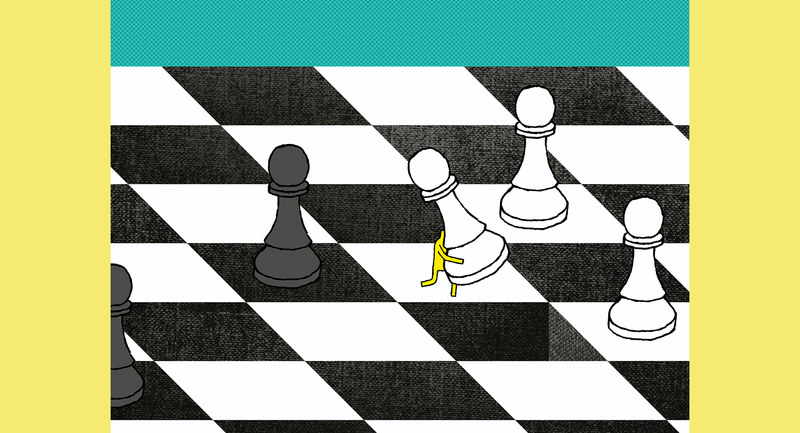

If you've been active on Twitter, you've probably noticed the exasperation that many teachers feel toward consultants they deem are "educelebrities." As a consultant, I have to admit bristling at the term the first time I heard it, but then, I also got it. I can recount too many professional development days where there was no choice and no differentiation at a high-priced presenter's performance, wishing I could instead be working on something I really needed to be doing. (On the flip side, as an inclusion consultant, I can tell you that there is nothing worse than being hired to "fill a PD day," knowing that most people don't really want to be there and that your efforts may not have any real impact beyond the day's entertainment.) But I've also had life-changing professional learning experiences that forever affected my practice. What is the difference between the two, and how do leaders select professional learning opportunities that make a difference in practice? How do we get beyond "entertrainment?" Here are a few questions to ask when making your professional learning decisions:

What is your "ethos?" Think about the Southwest Airlines model: What is it you want to be known for? What initiative(s) have you identified, including the input of teachers and students, that you want to focus on this year? Your school community may decide, for example, that this year you are taking on the initiative of increasing equity in outcomes for your students. This is broad and allows you to explore and hone many components. This purpose is your starting point in selecting professional learning. Nothing superfluous to that purpose should be considered.

How can you as a leader guide your teachers to identify their strengths, help them further cultivate these, and support sharing of expertise? Some of the best professional learning in a school is accomplished by teachers visiting one another's classrooms and reflecting together with purpose. When we build a culture of professional learning within the building and systematize a process for learning from one another's best, we create a machine of continuous capacity building. One teacher may identify universal design for learning as a need, and a teacher or building leader connects that teacher to teachers who have identified universal design for learning as a strength. Leaders start this process by leading teams to identify the values and practices that are salient to the current mission of the school. This forms the structure for an expert database. Leaders work with teachers to select those who have particular expertise and strength within each areas in the database. Other teachers then pair with the in-house experts to gain mentorship and coaching to grow their practice. We learn from one another in professional learning communities.

Once we have identified our strengths as a school, we can target those areas where we need external support. So often, when we think of professional development, we think of having a speaker for the day. But this is only one option—and an expensive one at that. Is spending thousands of dollars on a single-day required performance to the full faculty going to serve the purpose you have outlined? It depends on what that purpose is, but more often than not, the answer is "no." When we connect to external support, we want to make sure that support is integrated and is a relationship, rather than a single performance. Most of the time, an external consultant is best used to facilitate deeper, ongoing understanding and work shoulder-to-shoulder in solving implementation dilemmas. Consuming the content can happen via recorded video, books, or journal articles. Consultants should be skilled at learning about the individual context, culture, and climate of a school and assisting with the gritty implementation questions and practice.

Facilitated sessions are expensive, though, and leaders should expect more than a performance out of them. You are not only paying for the hours that a person facilitates, but their days or weeks in preparing. Frankly, if the session could have been recorded and your team get the same thing out of it—it SHOULD be a recording. Ask others who have used the consultant about their methods for engaging the participants. Is it all presentation with the only interaction as "turn and talk?" Does the consultant recycle the same slides and even jokes for years? Or does the person facilitate more of a dynamic work session that includes collaborative activities designed for processing or decision making and responds to the evolving needs of a group? Consultants should not only be experts in a content area but experts in facilitating active learning, processing, and action. Make sure your dollars are paying for excellent, responsive facilitation and a relationship, not simply an encore speaking performance that was largely designed a decade ago.

For any given initiative, not everyone in the school has the same needs or preferences for the same types of support. Just as we expect teachers to differentiate instruction for students, we need to offer differentiation to our teachers. Teachers are experts in their craft, not freshmen in college. They can identify their needs and know how they learn best. Some may prefer a facilitated session, others by learning with others in book study, still others through engaging in online content or courses and reflection. Even within a single initiative, everyone doesn't have to sit in the same all-day session to hear the same message and be involved. Leaders can facilitate an understanding of group and individual preferences for a given initiative and mobilize resources to these multiple options, rather than dedicating all resources to a single-day presentation.

Making complex change requires sustained engagement and is often best supported with ongoing coaching and consultation. Depending on the complexity and novelty of the new practice being implemented, a school may enlist external support for coaching and consultation. Even so, having on-the-ground coaching and consultation available for day-to-day work is a support that many teachers want and need. What is our system for using dedicated coaches as well as using teacher leaders as coaches to support the work? The work of Jim Knight, Bob Garmston, Art Costa, and Doreen Miori-Merola, among others, offer effective models of instructional and cognitive coaching for schools to consider integrating.

We would never evaluate the effectiveness of a lesson by how well the students enjoyed it, but rather the outcomes we want to achieve. Further, our teaching is more complex than a single lesson, but rather a complex web of our content and methods and transactions of learning between teacher and students. Similarly, the effectiveness of our professional learning isn't measured by how entertaining a one-day session is, but rather the outcomes on teaching practice and on student learning. Most initiatives are multi-year and include many methods of engagement, reflection, practice, and iteration.

Professional learning can be expensive, and leaders are charged with thinking about how to best spend those tightly budgeted dollars. In reality, although external consultants can add a lot, most of the learning and "stickiness" happens between consultant visits. This is when ideas are processed in context through dialogue, discussion, and day-to-day application. To make PD stick, we have to see professional learning as the much broader context within which any PD day or session fits. And for any of our initiatives, we need to make careful, outcome-focused decisions on the methods and people we select for both internal and external support. Otherwise, we may as well pop some popcorn and show an award-winning movie for our back-to-school PD day.