For a long time, our district kicked off the school year as most other districts did. The faculty gathered in the high school auditorium for a speech by the superintendent, who outlined our focus for the coming year. It was here that the Newtown, Connecticut, Public Schools, launched into Hunter, shared decision making, multiple intelligences, cooperative learning—and the list goes on.

We thought we were leading. We thought we were bringing practice into line with research.

We were wrong.

Over time, we created a scattered, disjointed pattern of programs and projects. Taken individually, they were fine. But by their very nature, projects and programs begin and end. They are the antithesis of continuous improvement.

We felt a pervasive uneasiness that although we met traditional expectations for student achievement, we fell far short of the kinds of successes we knew we could achieve. Without the perspective of quality, we were not sure of what to improve, or even which questions to ask.

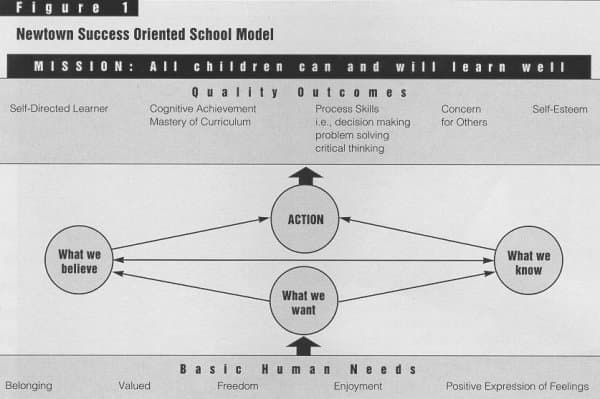

Two years ago, Newtown committed to changing the situation by becoming a total quality system. As we started our work, we became convinced that we could not simply adopt someone else's model of quality; we needed to develop our own. At a summer institute, administrators developed the Newtown Success-Oriented School Model (fig. 1), which became the cornerstone of our quality process. The model blends elements of Deming's 14 Points with Glasser's approach to quality.

Figure 1. Newtown Success Oriented School Model

Human Needs

We found that many models for achieving quality emphasize the work process and do not acknowledge psychological aspects of change. Glasser's Control Theory and Reality Therapy explain human behavior as needs-driven. People are internally motivated to meet their basic human needs for belonging, power, freedom, and fun (Glasser 1984). Because we believe that Glasser's ideas, which now extend into the area of quality schools (Glasser 1990), are critical (Freeston 1992), we designed our model to reflect the proposition that all wants come from unfulfilled needs.

Adapting Glasser's terminology somewhat, we acknowledge that people are internally motivated to meet their individual needs. Thus we train staff extensively in the role of human needs in our organization. The full training takes three years to complete, and shorter training options are regularly available to staff.

We also have discovered that considering the age of professional staff is important. With 84 percent of our certified staff over age 40, we felt compelled to address the different needs that staff members have at different ages. Working with Judy Arin-Krupp, we examined the application of adult development theory and research to our schools (Krupp 1981).

Model for Quality

Adapting Deming's quality canons is not an easy task for a district, and we have struggled with a variety of barriers (see fig. 2). But our model embodies Deming's work in several ways.

Figure 2. Attitudinal Barriers to Quality

Getting Started with TQM-table

The Word “Quality” Itself | Seen by many as a platitude, unobtainable, and oversued by advertisers. |

|---|---|

| The Corporate World as the Model | Skepticism about corporate example, rejection of customer orientation. |

| Leadership | Low confidence in leader commitment, scant examples of quality-oriented leaders. |

| Just Another Change | Regarded as another trend that will pass. |

| One Year at a Time | Quality is a long-range commitment and schools plan on a one-year basis. |

| I Know That Already | False perception that there's nothing new in a quality orientation. |

| Students Don't Value School | If only the students worked harder, we wouldn't need to improve schools. |

| It's Not My Fault | Changed social context of families presents insurmountable barriers to successful schools. |

| A Question of Culture | Belief that quality management is onoly achievable in Japan's culture. |

| Teacher as Self-Employed Entrepreneur | Teaching is an independent, isolated profession without the collaboration needed for a quality approach. |

The interaction of the four circles in the center of the Newtown model depicts how we now make decisions for improvement. Notice that no arrow connects a want directly to an action. When we were thinking conventionally in Newtown, we usually took action based on someone's statement of want: I want my child in Algebra, I want to offer an American Studies Program, or I want to offer French in grade 6. Because we spent much of our time responding to hundreds of requests like these, we had no notion of constancy of purpose or continuous improvement. We quickly learned from Deming's work (Walton 1986) the importance of consulting knowledge and core beliefs before taking action.

Knowledge. In our first year using the model, we viewed the “What We Know” circle as research-based. We joined a number of data-search organizations and quickly grew dissatisfied with the paucity of good syntheses on various topics. We now understand that collecting information, another Deming tenet, goes far beyond reading research reviews. Knowledge of student test scores is only part of what we need. Conventional assessment techniques offer data, not information, so we are developing alternate forms of assessment through the New Standards Project. Additionally, teams of teachers are establishing performance standards for Newtown students at designated grade levels.

Beliefs. The “What We Believe” circle is crucial to quality management. Working together for more than a year, our Quality Council developed a set of core beliefs. Defining the core beliefs of an organization is one thing; bringing group and individual behaviors into alignment with those beliefs is quite another. We feel our beliefs are part of a continuum, not absolutes. We must evaluate where practices and programs are located on the continuum and move them in the direction of the belief. For example, we may look at programs like Great Books at the elementary level, or Advanced Placement at the high school, to determine whether the way we choose students to participate aligns with our belief in inclusion. We will look at the way we make curriculum decisions for alignment with interdependence, and we will look at our grading practices for a match with our belief in success. Only after we consult our core beliefs and knowledge can we take action for school improvement.

The Quality Outcomes

In Newtown, we believe our mission is to provide an environment where “all children can and will learn well,” seven words that capture the essence of our constancy of purpose.

Many of our staff did not actually support the “all” notion, believing instead that changed social conditions and dysfunctional family settings present insurmountable barriers for some learners (Hay and Roberts 1989). But changes in students' home lives are important variables. Because a learner has more, or different, needs does not mean that student can't learn.

The word can expresses our commitment to multiple intelligences. We brought the work of Howard Gardner directly into the mission of the Newtown schools by acknowledging that every student has unlimited and multiple abilities. We reject the phrase “up to potential.”

- become a self-directed learner;

- achieve cognitively and master the curriculum;

- acquire process skills (decision-making, problem-solving, and critical thinking);

- show concern for others; and

- know the importance of self-esteem.

For the past year, teams of teachers have been defining the critical attributes of each outcome. District curriculums will then be modified to reflect specified efforts toward each outcome in each discipline.

What's Different Now?

After two years, what are we doing differently? The most obvious difference is that we are thinking differently and are guided in those thoughts by the logic of our model.

We have also changed our orientation for new teachers. Projecting our staff retirements to be substantial in the coming three to five years, we needed to design a way to welcome new professionals that balances their unique capabilities with our model and quality concepts. New teachers now spend a week with us in the summer, and the training will probably grow to two weeks. Gone are school tours with directions on how to find the copier, telephone, and coffee. In their place are the teachings of Deming, Glasser, and others.

Our general training is also different. The superintendent teaches a 12-hour course to staff, parents, and community members, focusing on Deming's 14 Points and their application in the Newtown Schools. A binder containing resources on quality is given to each course graduate and is updated monthly with new articles. There is also a course on applying Glasser's work on the role human needs play in our model.

Quality core groups in each school are beginning to shape their own allotment of inservice time and resources to address quality issues. When a redesign of the mathematics curriculum created some internal disruption and debate, we used some of what we had learned about continuous improvement. We brought together groups of teachers for problem-solving exercises and to design an improvement plan for issues they felt were important.

People often think that a quality orientation costs more money, but that's not what we've found. While our town is an affluent community, we spend less than the state average per student. Our wealth is in the top third of Connecticut towns, but our per-pupil expenditure ranks in the bottom third. Several local issues account for this: frequent referendums on school budgets pit interest groups against each other; longtime residents who prefer the rural character of a New England town resist requests for appropriate education funding from newer, pro-education residents; and other interests compete for local taxpayer revenues. It's been difficult keeping citizens focused on education funding when large expenses such as mandatory sewer construction require public funds.

Continuous Improvement

With an emphasis on continuous improvement, there is no rest. This is an important paradigm shift for professionals accustomed to annual projects and programs as the definition of change. In our third year of quality management in Newtown, we face several major areas of emphasis.

We need to stay close to the customer, never thinking we know all there is to know about the needs of students and parents. While acceptance for the idea of being customer oriented has grown, we really don't know how to do it well.

Convincing staff that our quality orientation is not a quick fix also needs work. Our staff members have centuries of combined experience with school leaders jumping on the bandwagon of the latest change. Deming's claim that nearly 90 percent of all organizational problems are management problems forces us, as school leaders, to acknowledge we have a past to overcome.

Through training and application, we want to expand our understanding and use of tools such as histograms, run charts, and Pareto charts. They should be as common as plan books and are far more useful. By training students and all employees in their use, we can convert data into information that will help us place both student and program evaluation in the proper perspective.

We have recognized the need to apply quality management techniques to problem solving at all levels of the school system. In the short run, this means training a team of facilitators to be available throughout the district. In the long run, it means that continuous improvement must guide our thoughts and actions.

Long-Term Approach

Any school district considering quality management needs to struggle with its own issues and develop its own model; adopting another person's model will be regarded as just another external pressure for change. Quality has already become a marked term in some educational circles. Journals, workshops, and consultants have popularized, and thus diminished, its significance. In a very short time, some educators have taken a long-term, continuous improvement model, converted it to a quick fix, and killed it.

The Newtown schools are committed to a long-term approach to school improvement. We are confident in our model, in part, because it is our own synthesis of knowledge and experience. When we acknowledge that the student is the customer, learning is the product, and teaching is the service, we put ourselves in the position of achieving legitimate school improvement.