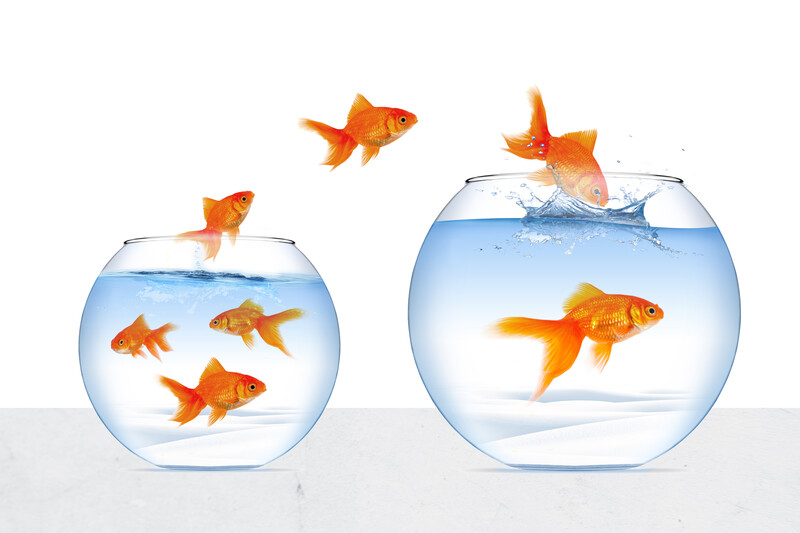

The demands facing today's schools have grown. In the last century, schools settled for educating most students in the three Rs—reading, 'riting, and 'rithmetic. Today, schools must educate every student to high levels in a much wider range of content areas, while also ensuring they are healthy, safe, engaged, supported, and challenged. Our schools must stretch to meet those demands.

Educating every student for the 21st century requires knowledge, skills, and dispositions that are far beyond what any one educator could individually master, but which certainly could be demonstrated across a faculty. However, to ensure all students benefit from such expertise and experience, schools must be designed for collaboration around teacher learning, teaching practice, and shared decision making. This is something many schools are not currently structured to support.

When teachers feel there are logistical or cultural barriers to asking for help or providing advice that could bolster a colleague's learning and effectiveness, critical opportunities for improvement are lost. When teams do not have productive collaborative planning time, each student's learning is limited by the knowledge and skill of the one teacher to whom they are assigned. And when schools do not have routines for involving teachers in school-level decision making, critical decisions meant to support teaching and learning can inadvertently impede them.

Still, the demands on today's schools call for everyone to be a positive influence on the quality of one another's work. This requires teachers and principals to create the structural and cultural conditions needed to work together and to share responsibility for improved student learning. For this to happen, schools need shared leadership.

Research suggests that where leadership is widely distributed, its impact on student learning is greater. When reorganizing schools for shared leadership, tools, strategies, and models can help. Yet, teachers and administrators alike should expect some growing pains as they work to incorporate these supports, find their rhythm, and strive toward leading in sync.

In many schools, principals create a vision and work to gain buy-in from the community to embrace that vision. For their part, many teachers are accustomed to having only two choices: follow the principal's lead or close the classroom door and do their own thing.

There may be some pushback, then, as schools move toward shared leadership, and as the principal shifts attention from being the vision-creator toward engaging the community in developing a shared vision. Principals and teachers alike may become frustrated by this more time-consuming process and may feel anxious about the new responsibilities that shared ownership inevitably brings. Yet the risk will be worth the reward as a truly shared vision empowers all to be stewards of that vision.

In some schools, principals are used to holding all the cards. In others, principals make an effort to share responsibility by "distributing leadership," as though they are dealing their cards, while teachers may volunteer—or be "volun-told"—to take a card.

Shared leadership, by contrast, recognizes that teachers and administrators have complementary expertise and that a mere redistribution of responsibilities through delegation is a lost opportunity. Schools with shared leadership have routines to leverage the perspectives of both groups. Some, for example, establish teams in which teachers and administrators engage in collaborative problem solving to address schoolwide issues, or develop a weekly protocol that invites teachers to weigh in on a list of upcoming decisions.

As a rule, such schools have strong communication routines that ensure the right hand knows what the left hand is doing as teachers and administrators co-perform leadership. Growing pains arise when administrators cling to traditional roles and org charts instead of thinking differently about the diverse experiences and expertise every teacher brings to their work, or when norms of egalitarianism, privacy, and seniority interfere with efforts to position teachers where they can make the most difference. Where they succeed at shared leadership, though, schools will more effectively and efficiently maximize each educator's assets as resources for improvement—and students will be the beneficiaries.

Some school and district leaders view teacher leadership as an "initiative." They begin by selecting teachers and possibly even preparing them for leadership roles before they have a plan for how these teachers will be positioned to influence teaching and learning. Under other leaders, teachers may struggle to gain "permission" to lead or be challenged by the assignment of "teacher leader" titles with loose support and vague role responsibilities.

Where there is shared leadership, teaching and learning come first. Because educators in such contexts are collectively committed to doing whatever it takes to advance teaching and learning, they direct their attention to what students most need, which actions should be taken to address those needs, and where each educator can plug in to have a real impact on the success of these efforts. While this may involve formal roles for some teachers, every teacher assumes responsibility for being a positive influence on the quality of one another's instruction. Principals and teachers alike may experience some confusion and even a sense of loss as they move away from neatly self-contained roles and place greater emphasis on creating conditions for interdependent and responsive interactions among all teachers.

Educators are kind folk. We enter the field of education with a sense of service and a duty of care. We celebrate each other's birthdays and honor one another upon retirement. But do we trust in each other enough to expose our true hopes as we work toward a shared vision? To risk disrupting routines to create new routines that can support co-performance? To abandon norms that have grown comfortable to take a chance on a culture of shared leadership?

Educators committed to shared leadership recognize that the reward is greater than the risk and that the risk requires trust. They don't take trust for granted, but commit to the intentional cultivation and ongoing nurturing of it. It's the secret sauce that makes growth possible.

The shift to shared leadership can be scary, frustrating, confusing, and, at best, awkward. Educators who enter this work with an awareness of the challenges ahead, an understanding of the importance of trust for mediating them, and a commitment to leading in sync, are at a true advantage. Retooling schools to support shared leadership is our best hope for meeting each and every student's needs. With collective commitment, we can grow the schools students deserve.

End Notes

•1 Leithwood, K., Harris, A., & Hopkins, D. (2008). Seven strong claims about successful school leadership. School Leadership and Management, 28(1), 27–42.

•

2 Berg, J. H. (2018). Leading in sync: Teacher leaders and principals working together for student learning. Alexandria, VA: ASCD.