Almost without exception, past reform initiatives of public schools have encountered opposition from one or more constituencies. Whether reform is primarily logistical—as in instituting a year-round calendar—or more philosophical, as in authentic assessment, opposition is virtually guaranteed. In general, no area of public education has generated as much controversy as school-constituent relations.

Why have these problems arisen again and again? Because we have not come to grips with the basic philosophical differences that underlie almost all public school controversies.

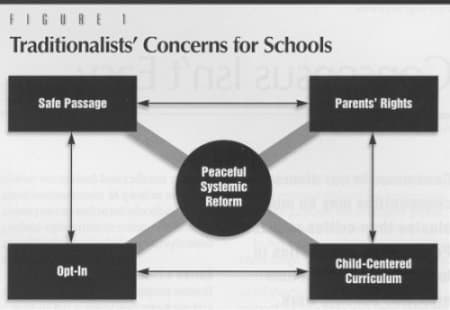

Sources of Conflict

- safe passage

- opt-in

- parents' rights

- child-centered curriculums

Figure 1. Traditionalists' Concerns for Schools

I maintain that it is possible to achieve community consensus, as well as peaceful—or at least less stressful—systemic educational reform, but only if we clearly articulate and respond to these differences of opinion. Doing so will require many public school administrators to make a fundamental paradigm shift.

Safe Passage

Public school policies, such as those requiring metal detectors, reflect society's recognition that the physical safety of students must be guaranteed. Students must be able to pass safely through territory that can appropriately be described as hostile. By safe passage, I mean learning environments in which all students can complete courses without having their values or beliefs assailed or ridiculed, either explicitly or implicitly. Regardless of their family's ethnic or religious identity, students will not be physically assaulted, emotionally or intellectually accosted, or spiritually molested.

Traditionalist Christians have perceived a need for safe passage. Many school officials have accused this group of wanting to take over the schools and impose a Christian agenda. But although that allegation may be justified in isolated instances, in the majority of cases, these parents simply want safe passage for Traditionalist Christian students.

Opt-In

In Adams County School District 50 in suburban Denver, many parents objected to the showing of the movie Schindler's List to high school students. Parents argued that the movie's R-rating, violence, and nudity rendered it inappropriate for use in high school classrooms. They requested that a documentary on Oskar Schindler be shown instead. District 50 schools accommodated these parents. The school district had adopted an opt-in policy.

Prior to its paradigm shift, the district had allowed parents to remove their children if the parents objected to the showing of films, but parents complained that students who were removed were often ridiculed. After reviewing a petition from 138 parents requesting alternatives to materials they found objectionable, a district committee recommended that R-rated films be shown only to students whose parents granted explicit permission.

Now, teachers who want to use such materials must first send a letter to each student's home, explaining why the material will be used. Parents may then opt-in by signing permission slips. This is a departure from common practice, which requires parents to discover, on their own, and often after the fact (and in the heat of emotion), potentially offensive elements, and then to request permission to have their child excused. Opt-in requires that parents be asked ahead of time—with polite and friendly questions—which topics, practices, materials, or concepts they might find offensive. Then, when any potentially offensive curriculum element emerges, school officials contact those parents and ask them whether they want their children to participate.

To be sure, opt-in may be more inconvenient for school personnel; it creates logistical challenges, such as scheduling and provision of individualized alternatives. But it also minimizes the magnitude of problems by obviating the emotional aspect of parental concerns.

Parents' Rights

In the last two decades, there has been an implicit assumption that societal imperatives are all-encompassing—that parental concerns are an encroachment upon the schools' prerogatives.

For example, in another Denver suburb, parents objected to teachers showing two American Cancer Society videotapes—one on breast self-examination and the other on self-examination for testicular cancer—to groups that included both boys and girls. In response, according to news reports, teachers canceled the films. Apparently they saw parents as interfering with the school's prerogatives.

A simple paradigm shift would significantly reduce such conflicts. The community must clearly spell out which requirements it believes all students must meet in order for society to survive. And it must spell out which areas of parental/family rights are inviolable and not subject to government intrusion or regulation. Realistically, no community will reach total consensus on the issue. But inevitably, both the number and intensity of conflicts will go down as imperatives and rights become less ambiguous.

Child-Centered Curriculums

For some school districts, the idea of a child-centered curriculum would not require a paradigm shift. In many districts, however, curriculums have evolved so that their primary purpose is to train citizens who can help make our society more internationally competitive.

A society-centered curriculum addresses society's needs by mandating certain content and skills for all citizens, regardless of individual proclivities or talents. (For example, if we need people proficient in mathematics more than we need musicians, and if we are working with limited time and capital, we stress mathematics. We may even drop the music program and use the financial savings to buy computers.)

A child-centered curriculum, in contrast, attempts to identify specific strengths, talents, and gifts of students; it then individualizes instruction to maximize the development of these attributes. Such a curriculum is rooted in two beliefs: (1) individuals will eventually gravitate toward self-fulfillment, and so will focus on aspects of the curriculum they value, and forget things they don't, and (2) society is strengthened most by the diverse contributions of people whose gifts are most fully defined.

This philosophy holds that we're better off as a society if we bring out the best in each student, and draw from the talents that develop as a result. It is only logical, therefore, to make sure each child's passage through a public school is emotionally, intellectually, and spiritually safe. And to do this, we must have maximum parental input, and also specify where parents' rights begin and end.

New Paradigms for Reforms

Now to apply these four philosophies to reform. Authentic assessment, to return to this example, fits the learner (it is child-centered); and it is advocated by proponents of outcome-based education. The student is assessed based on his or her accomplishment of a real-life experience, not just some hypothetical sample.

When authentic assessment stresses students' attainment of outcomes adopted by the community, society's imperatives are addressed. When the process focuses on parents' opportunity to opt-in when they perceive that safe passage for their children is not in danger of being violated—in terms of the assessment outcomes or the methodologies or materials employed—parents' rights are addressed.

The four philosophies—safe passage, opt-in, parents' rights, and child-centered curriculums—are thus satisfied. Chances are good, then, that conflict between the school and its constituents, if there is any, will be problem-focused, rather than emotion-focused. We can shed light without generating heat. By making the paradigm shifts necessary to achieve harmonious reform, we have nothing to lose, and everything to gain.