The positive impact of coaching on teaching and student outcomes is becoming more and more indisputable. But the devil is in the details. Specifically, there are certain key ingredients that we know contribute to the success of the coaching process: pairing coaching with professional learning opportunities; ensuring coaching cycles include observation, modeling, and providing performance feedback to teachers face-to-face, virtually, or both; and customizing the dosage of coaching (Kraft, Blazar, & Hogan, 2018). Perhaps the most important ingredient is to ensure coaches have a positive alliance (or relationship) with teachers (Gessnitzer & Kauffeld, 2015).

Why are teacher-coach relationships so important? Positive relationships serve as the foundation for all the work coaches conduct with teachers. That is, when positive relationships are in place, teachers are primed to be observed by their coach, to see their coach model how to implement a practice, and to receive positive and corrective feedback on their teaching.

Moreover, teachers with a positive coaching alliance tend to show greater improvement in instruction than teachers who have negative relationships with their coaches (Wehby et al., 2012). Thus, the teacher-coach alliance can influence the attainment of coaching goals—mainly, improved teaching—which in turn can influence the degree to which students show improved learning outcomes.

Three Strategies for Alliance Building

If relationships play such a make-it-or-break-it role in coaching, what can coaches do to build and maintain a strong alliance with teachers? To answer this question, let's turn briefly to research on alliance building for a different professional role: therapists. It turns out that a therapist's efforts to create positive relationships with his or her clients is extremely important. In fact, a positive therapist-client alliance is one of the most powerful predictors of therapeutic success (Horvath, 2001).

Knowing this, expert therapists use specific strategies to build and maintain a positive alliance with their clients, all of which relate back to three factors that comprise alliance: (1) effective interpersonal and communication skills, (2) collaborative partnerships, and (3) professional expertise (Horvath, 2001). For example, effective therapists demonstrate a warm demeanor and use nonjudgmental language to create a climate of trust. They ask clients to identify their therapeutic goals and the respective tasks they will undertake to reach those goals. They also offer relevant and digestible resources and advice that is directly applicable to the needs of the client (Horvath, 2001). Good coaches do these things, too.

To be clear, this discussion of research on therapeutic work is not intended to imply that providing therapy and conducting coaching are one in the same. Rather, it illustrates that the same three types of alliance-building strategies that successful therapists use can also be used by instructional coaches (Pierce, 2015).

Although some coaches may instinctively use these strategies with teachers, building positive alliance requires skill and intention. Unfortunately, coaches typically receive little, if any, formal preparation in how to build relationships with teachers. In addition, coaches and teachers can experience damaging fissures in their relationships, particularly when teachers face job stressors or when coaches attempt to push teachers toward making difficult changes (Johnson, Pas, & Bradshaw, 2016). Given these challenges, it is essential that coaches learn concrete strategies for building positive alliance (Kraft et al., 2018).

1. Use Effective Interpersonal and Communication Skills

From the onset of their work with teachers, skilled coaches use strong interpersonal and communication skills. This means that they pose open-ended questions, listen more than speak, and summarize teachers' ideas. For example, a coach might ask a teacher a broad question about newly learned practices ("What are your reflections on culturally responsive management practices?"), then briefly restate key points the teacher verbalized. The coach might then ask additional questions to deepen the conversation ("Can you tell me more about why that particular practice is important for your students?"). The idea here is to elicit information from the teacher to demonstrate that her perspective is valuable. Below are additional examples of open-ended coaching questions. Note that the first two questions can be used any time with teachers (in the first coaching session and thereafter), but the remaining questions are most applicable once coaches have conducted observations.

How do you envision us working together?

What changes are you considering making to your teaching practice?

How did you work through this kind of situation in the past?

What did students learn?

Another way to show strong interpersonal and communication skills is to build trust with teachers. Easier said than done, particularly when a teacher-coach dyad is new to working together or when teachers are less than thrilled about coaching. If teachers (directly or indirectly) communicate they aren't receptive to coaching or if the partnership is new, act immediately; a lack of trust can be one of the most formidable ruptures in a teacher-coach alliance (Johnson et al., 2016). For example, fulfill commitments made to teachers to show that you will do what you say you will do. Many coaches promise only to share high-level summaries of coaching with administrators, not play-by-play reports of their work with teachers. Keep this promise. Also, verbalize that coaching isn't a one-way learning experience but one that enriches both parties. Try sharing personal coaching or teaching missteps to highlight that everyone struggles at one time or another; this helps teachers feel more comfortable expressing their vulnerabilities.

2. Create Collaborative Partnerships

Good coaches create collaborative partnerships with teachers in which invested teachers have ownership in the dyad's work. One productive way to create such a partnership is by asking teachers to identify the goals they would like to accomplish. A coach might ask, "What would you like to achieve from our coaching sessions?" Asking this question upfront indicates to the teacher that coaching is driven by their needs.

In general, avoid prescribing a goal for teachers. Unless the teacher specifically asks for the coach to set the goal, prescribing a goal may inadvertently give the impression that the teacher's professional needs are unimportant (Johnson et al., 2016). The alliance, in turn, is likely to suffer. To avoid this pitfall, ask teachers to identify their strengths and areas for improvement. Then guide teachers toward identifying a professional goal. The coach's charge is to help teachers address their perceived needs—even if those needs are different from what the coach envisioned. Coaching is not about fixing teaching; it is about helping teachers continuously develop so that all students are successful.

Once a goal is set, ensure that it is at the forefront of every coaching session. Some coaches and teachers like to draft a simple action plan to keep the goal as the focal point of coaching activities. It might include goal-related questions such as, Who will do what? By when? and What happened?

Whether or not an action plan is created and followed, allocate time for teachers to reflect on what's transpiring in the classroom as they progress toward their teaching goal. When asking teachers to reflect, encourage them to highlight the positive aspects of their practice while acknowledging one or two improvement areas. Celebrating "wins" with teachers affirms that coaching sessions are about both honoring teachers' strengths and gradually working on areas of improvement.

3. Demonstrate Professional Expertise

Finally, skilled coaches humbly demonstrate professional expertise when working with teachers. This does not mean it is necessary for coaches to champion their professional successes or spout off a litany of knowledge. Teachers simply need to know that they can rely on a coach to help them successfully navigate complexities that arise in the classroom environment. Therefore, it does mean finding ways of leveraging what the coach knows so that new—and experienced—educators can advance their teaching practice.

For example, help teachers unravel why a particular issue occurs in the classroom, such as challenging student behavior. In tandem with the teacher, pinpoint small steps he or she can take to immediately reduce or resolve the issue. Observe the teacher, collect relevant data (like occurrences of praise statements to students compared with redirection statements), then meet with the teacher to share the data. Next, ask the teacher to reflect on what the data mean for improving practice.

Ensure that critical coaching practices (observing, modeling, and providing performance feedback) are the cornerstone of coaching sessions—but know that these practices, too, can be used flexibly based on the needs of the teacher. Finally, offer relevant but simple resources (such as a graphic organizer for a vocabulary lesson with English language learners). If a teacher is unsure how to use the resource, set up a time to walk them through it or cocreate a lesson plan that spells out how the resource will be used. These strategies allow a coach to demonstrate expertise without coming across to the teacher as unapproachable or all-knowing.

A Balanced Approach

Now that these alliance-building strategies have been laid out, there are a few tips worth noting to facilitate coaches' use of them. First, keep in mind that alliance building occurs throughout the life of the partnership, not just at one time or another. Once an initial positive relationship has been established, maintain the alliance by continuing to integrate these strategies into all work conducted with teachers.

At the same time, you don't want to focus on alliance building so much that the "heavy lifting" of improving teacher practice—conducting observations, modeling, and providing performance feedback—is neglected. A good rule of thumb is to focus on alliance-building strategies in initial sessions, but to not dedicate so much time to it that the other work of coaching suffers. Alliance building, by itself, won't produce improved teaching.

Second, be flexible in the use of alliance-building strategies. Teacher-coach relationships, like all other relationships, experience peaks and valleys. During relational valleys, it may be helpful to revisit strategies across the three types (effective interpersonal and communication skills, collaborative partnerships, and professional expertise). During peaks in alliance, the coach may find it less necessary to do so. Become comfortable adjusting the use of the strategies based on the needs of the teacher.

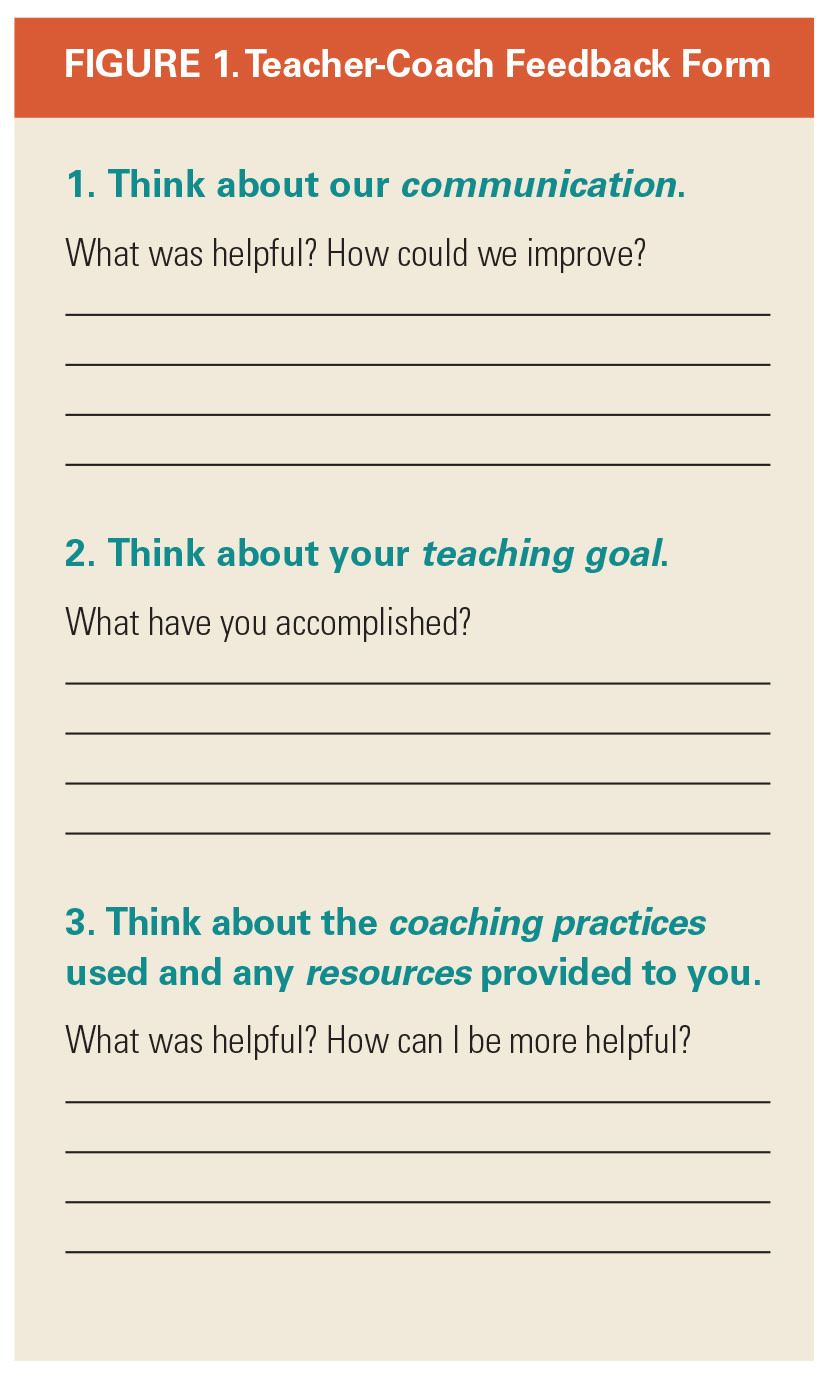

Unsure about teachers' alliance needs? Try using a teacher-coach feedback form (see Figure 1), to gain insight into teachers' perceptions of alliance. This form contains three points of reflection with follow-up probes. Each question subtly links to one or more of the alliance-building strategies. In a pilot study examining a similar version of the form (Pierce, 2015), coaches and teachers found it to be a valuable tool for building and maintaining an alliance.

Alliance-Building as a Learned Skill

Coaches, like therapists, recognize that relationships are foundational to their work. Yet too often coaches are expected to naturally possess "soft" skills like building and maintaining an alliance. As a field we can do better than to make this assumption. Schools can get the most out of coaching by treating alliance building as a practice that can be learned and applied to every coaching session.