One teacher's journey to overcoming instructional confusion.

Reading is one of the most unnatural things that we teach children to do. It's not like learning to talk, which for most children comes naturally as a result of hearing spoken words. It's also not a matter of simple memorization, which kids can also pick up very early.

When we talk about a school-aged child's ability to read, we mean that she can decode the words, assign meaning to them, and comprehend what has been read. As an early-grades educator, I found that this skill is best developed through direct instruction in phonics in the context of engaging reading material—but it took me a while to figure this out.

The whole-language approach to teaching reading has long been determined to be insufficient on its own. However, as journalist Emily Hanford has pointed out, you can walk into almost any kindergarten or 1st grade classroom in the United States and see a "word wall" meant to spark visual memory and see students guessing at words to match the pictures on the page. The idea that simply exposing children to words and books and reading to them is the best way to create good readers has a powerful, mysterious hold in schools.

Most early educators know on some level that phonics instruction is an essential part of any literacy curriculum. The problem is that we often don't know how to do it—and our own uncertainties are compounded by erratic instructional policy decisions made above us.

As a third-generation educator, my destiny to become a teacher was sealed long before I ever took an exam or wrote a lesson plan. I began teaching children how to read during my freshman year of college as a volunteer for an after-school tutoring club at the local elementary school. I continued teaching reading when I became a classroom teacher, working as a preK and elementary teacher in Washington, D.C., Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, and Houston.

Over the course of 15 years in education, I was mandated to implement at least eight different literacy curricula. Some were dull and heavily scripted programs focused strictly on phonics, while others took a more whole-language approach. None left much room for nuance, teacher discretion, or student interest. In school systems, there's often a tendency to hop onto the "innovative" new thing before giving the current initiative a chance to come to fruition. This does not make teaching easy.

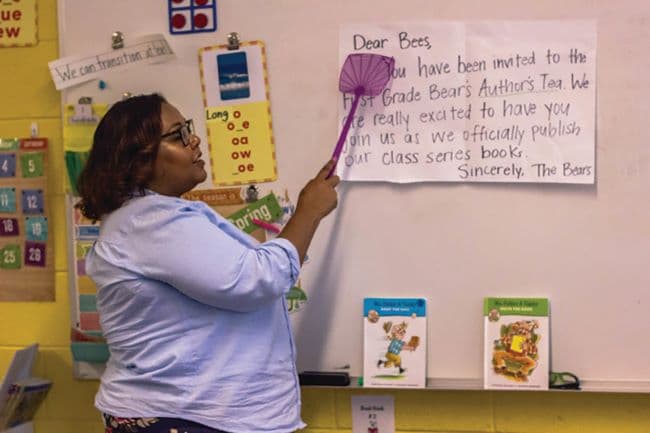

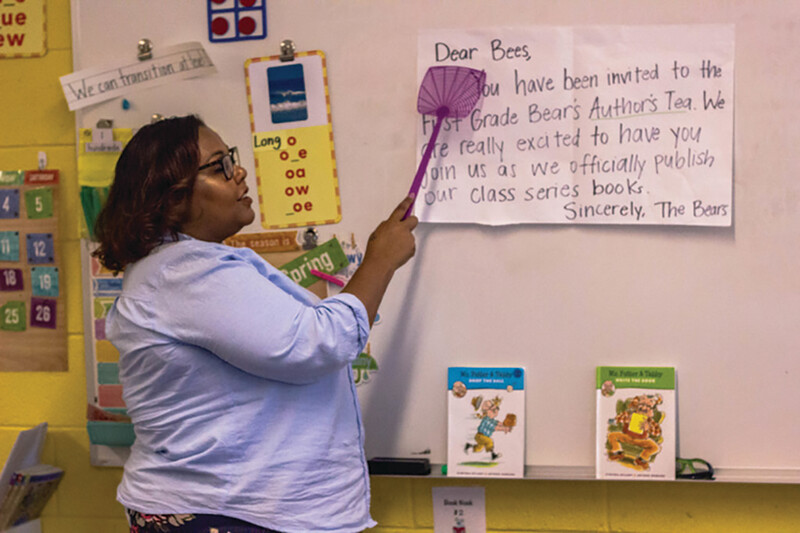

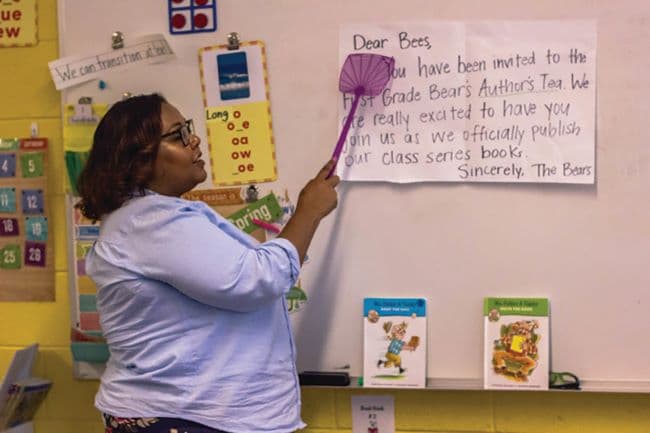

There came a time, however, when I became frustrated with my professional development days being filled with training on our newest (usually less flexible) literacy program when we hadn't even mastered the last one. Frustration leads to rebellion for many teachers, which is why we've often adopted the idea of "closing the door and just teaching." That's what I did.

By closing my door and just teaching, I figured out how to teach my students to read. I took what I liked about each of the literacy programs I'd been exposed to and what I knew about my students, and just taught. I taught my students consonants and short vowel sounds, then long vowels, and finally consonant blends. Having students be able to sound out the words on the pages of the books they were already excited about made the risk of rebellion worth it.

Having a selection of diverse and culturally relevant books was also important for getting my students interested in reading, and it was helpful in providing context for vocabulary building, which is essential for improving comprehension. In my kindergarten classrooms in both Abu Dhabi and D.C., one of my students' favorite books was The Name Jar by Yangsook Choi, about a girl's journey to find pride in her name and identity.

I figured out that I could teach students to read so that they could then read to learn. This meant doing a significant amount of direct, specific instruction on spelling and sound sequences in words, as well as catering to students' individual needs and reading interests.

If we believe that education is the great equalizer, then we must give children the best we have to offer. Many studies, like David Liben and David Paige's "Why a Structured Phonics Program is Effective," tell us that if we want children to learn this unnatural thing called reading, we must adopt meaningful phonics instruction. As a matter of educating the whole child, administrators must support this movement by giving teachers the opportunity to learn and adopt this method in a way that gives them the flexibility to get students excited about reading.

The greatest lessons I learned when I closed my door and just taught were that my students were always capable of more and that the expectations they had for themselves were always growing.

End Notes

•1 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: Reports of the subgroups. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

•2 National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. (2000). Report of the National Reading Panel: Teaching children to read: Reports of the subgroups. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

•3 Liben, D., & Paige, D. (2017). "Why a structured phonics program is effective." New York: Student Achievement Partners.

•