Without question, 2020 was a year for innovative teaching. The teachers we worked with in professional development sessions around the world wholeheartedly plunged into hybrid schedules, synchronous teaching, and asynchronous classes. They experimented with blended learning, hoping the models that propose individualization using digital resources would increase student engagement, creativity, and higher-order thinking. Teachers pored over online resources to solve problems and made decisions about how to use technology to motivate students.

As teachers used digital programs and video, they sought feedback and revised their teaching; in short, they innovated. Tyler Douglas, a history teacher we worked with, admitted that prior to the pandemic, he considered technology-assisted instruction optional in conjunction with in-person teaching; now, he believes blended learning is here to stay.

His question to us was: Did that year of innovative teaching result in students learning to be more innovative, too? In other words, since teachers experimented, solved problems, and made decisions about using technology, was it true that students also developed those same critical and creative thinking skills?

Innovative teaching means the teacher is the creator, but unfortunately it does not necessarily mean the same for the students. Innovation is not just doing something new; it is thinking of new ways to improve a product, a method, or an idea. How can educators like Tyler teach students to become better innovators themselves? We believe there are three key adjustments to lesson planning that can help them: (1) teach declarative knowledge so that it sticks, (2) teach thinking skills explicitly, and (3) use technology to maximize access to information.

1. Teach Declarative Knowledge So It Sticks

Neuroscientists confirm that structural components of the human brain uniquely process different types of knowledge. For instance, procedural knowledge, such as reading, computing, singing, and drawing, is best learned through practice. This type of skill-based knowledge can be hard to learn because it requires a lot of practice, but it is also hard to forget. Once you have learned how to ride a bike, you have learned how to ride a bike forever. The result of successful practice is the ability to replicate the procedural knowledge.

When the "practice" approach is used for declarative knowledge—such as facts, concepts, and information—however, the result is memorization, and usually only for the short-term. Do you remember studying the content for a test and forgetting it within a few days? Most students feel the same way.

In contrast to procedural knowledge, declarative knowledge is easy to learn and just as easy to forget. So let's consider: Is it important for declarative knowledge to be retained in long-term memory—and, if so, why?

In his book, The New Executive Brain: Frontal Lobes in a Complex World, Elkhonon Goldberg (2009) describes the brain as an orchestra, with the pre-frontal cortex as the conductor. He observes that the fortuitous "emergence of language and the advent of the frontal lobes" contribute to how we connect new sensory data and declarative knowledge with our previous experiences to make meaning (p. 23). This generative transformation, or thinking, leads to new ideas, or innovation. And it makes sense that the more knowledge you retain, the more productive your thinking. Indeed, we believe that teaching declarative knowledge so that it sticks—so that it is retained in long-term memory—is a cornerstone of innovative thinking.

Research suggests techniques to help students remember material better. In Classroom Instruction That Works, one author of this article (Jane Pollock) and her colleagues introduced nine high-yield strategies teachers can teach students to help them retain information (Marzano, Pickering, & Pollock, 2001). In order of effectiveness, they are: identify similarities and differences; summarize and take notes; reinforce effort; practice; use nonlinguistic representations; use cooperative learning; set objectives and feedback; generate and test hypotheses; and employ questions, cues, and advance organizers. A teacher should plan lessons to ensure that students regularly use these high-yield strategies.

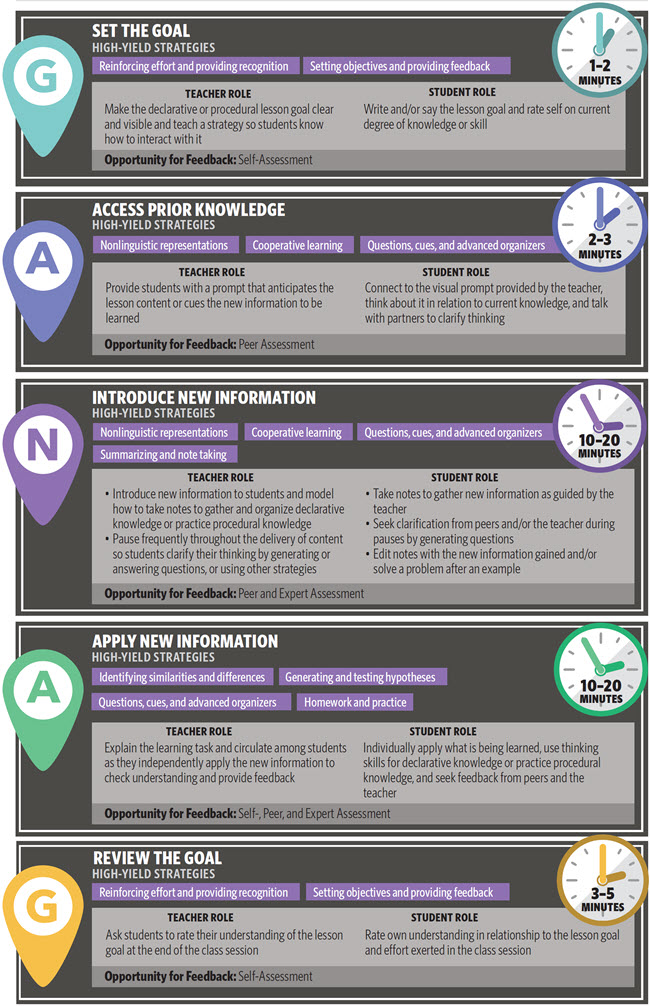

To support such planning, we have adapted Madeline Hunter's Master Teaching lesson plan model to incorporate these strategies. Our Master Learners schema involves five steps—set the goal, access prior knowledge, introduce new information, apply new information, and review the goal (known as GANAG for short). It also includes ways a teacher can deliver lessons to actively engage all students by teaching them to use the strategies (Pollock, 2007; Pollock & Tolone, 2020). Figure 1 shows how to use GANAG. Each step in GANAG states the teacher action and describes how to actively engage all students during the lesson.

Figure 1. GANAG: 5 Steps for Every Lesson

Source: Pollock, J. E., Hensley, S., & Tolone, L. (2019). High-Quality Lesson Planning (QRG). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

For example, one math teacher who worked with us used to write his learning objective on the board, assuming students would read it. Now he teaches students to write down the objective and pre-assess their knowledge and their effort. Students assess themselves again at the end of class to gauge their learning. Students noticed that when they increased effort, they learned the math better. In only a few days, students began to ask for the objective and often would question its connection to previous goals. Their engagement, the teacher says, has allowed the objective to serve as the students' learning intention, rather than it being purely teacher driven.

Similarly, another teacher we worked with, Trish Harry, used to review the previous day's lesson at the start of each class. Now she deliberately plans for students to access prior knowledge, step 2 in GANAG. Trish shows a visual and provides a question for students to discuss in pairs (cooperative learning). She might show a political cartoon or an image of an artifact (nonlinguistic) to cue the new information tied to the goal. Trish notes that her lesson reviews in the past only engaged five or six students, whereas using an image and pair/share in this step piques every student's attention every time.

In the past, chemistry teacher Amber Greer would spend her planning time creating slides for her class; now, using GANAG, she designs her slides to teach students how to take notes during the Introduce New Information phase (note taking). She adds "pause" slides between her content slides and teaches students to use interactive notebooks, so they have time to think about the content. They might add information to a diagram (nonlinguistic), talk with a tablemate briefly about an issue (cooperative learning), or generate questions to connect more deeply to the content (questions). The frequent pauses re-engage students during this phase, increasing the likelihood that they will retain the information.

Teachers who intentionally plan for student engagement in these ways have reported that their students' long-term retention of declarative knowledge noticeably increased. Then they could tackle the next step: teaching critical and creative thinking skills.

2. Teach Thinking Skills

Returning to how the brain functions, Goldberg writes that humans, uniquely, can "create models of something that does not yet exist but that one wants to bring into existence" (p. 23). To adapt one of the examples Goldberg provides (2009), it makes sense that you do not need to use your frontal lobes to remember what a person looks like or to make a mental image of a bird, but you do have to use your pre-frontal cortex to think of how to design a way for humans to fly. When we think, we generate new ideas. We innovate.

In their daily lives, students are exposed to volumes of stimulation and information that makes them think about which song to purchase online, how to analyze their schedules to find time to attend a party, or how to compare various restaurant options. Given that students are already thinking naturally to process the world around them, why would we argue that teachers should explicitly teach thinking skills in school? Because many of students' assignments ask them to remember information, but not to compare, analyze, or make associations about the topics in the same way they do in their daily lives. To teach innovation, teachers can explicitly teach thinking skills by encouraging students to think about the declarative knowledge within the lesson's goal.

To teach thinking explicitly, our GANAG framework suggests using some of the 12 skills listed in The i5 Approach: Lesson Planning that Teaches Thinking Skills and Fosters Innovation (Pollock & Hensley, 2018), such as, classifying, using analogies, analyzing perspectives, investigating, and finding logical fallacies. Each of the thinking skills includes a series of steps. Here's one example:

Systems Analysis: Know how the parts of a system impact the whole.

Identify an object, event, or thing as a system.

Describe its parts and how they function.

Change a part or function and explain how that affects the whole.

Change other part(s) and explain the results.

Summarize and use the findings to generate deeper understandings or an improvement to the system. (Pollock & Hensley, 2018)

Many of students’ assignments ask them to remember information, but not to compare, analyze, or make associations about the topics in the same way they do in their daily lives.

Adapting this approach, a history teacher like Tyler Douglas might plan a lesson about the settlement of the West in the United States. After the lecture and discussion, he could teach students to apply the newly acquired declarative knowledge by using systems analysis. Tyler could then frame the time period as a system and suggest that certain changes, such as revising the Homestead Act or relocating the Transcontinental Railroad, would result in different settlement patterns. This type of thinking task allows students to deepen their understanding of history while generating new insights about historical concepts.

Of course, teachers from all disciplines can teach thinking skills. A math teacher can use classifying as a method for 1st graders to learn the differences among shapes; a middle school science teacher can teach students to use analogy to describe the endocrine system like a vending machine; and physical education students may investigate ways that people recover from different types of exercise and sports injuries. To think deeply, students need to learn to use thinking skills, and they need a lot of information about the topics. That leads us to the third aspect of lesson planning for innovation: using technology to maximize access to information.

We have explained why and how to teach students to retain declarative information and use thinking skills, yet the question remains: Where can students access enough information that can lead to deep thinking about any given topic in a school's curriculum? We expect that most educators will have a resounding answer—the Internet.

In the world outside of the classroom, we see, hear, smell, touch, and taste as ways to gather information. Traditionally in school, students have only been able to see and hear about a topic from a teacher. Textbooks and print materials can only provide so much information and generally not enough to create the environment that engenders deep thinking. When a teacher plans lessons that incorporate technology, however, students have access to almost infinite multisensory stimuli.

The concept of the i5 Approach mentioned above emerged from blending the current expectation that students use technology in school with the neurological finding that people need to know a lot to think productively. By searching online, students can literally find something to "think about," to generate better original ideas. Searching online provides more than just basic textbook information. It can also provide video, pictures, diagrams, opportunities to modify models, and ways to seek and receive feedback.

The i5 Approach calls for teachers to show students how to use their devices during the instruction or new information part of a lesson, as opposed to using them only for the guided practice or independent practice. When teachers plan lessons for teaching students to use critical and creative thinking skills, they should consider how to maximize access to information. When planning lessons, teachers can ask themselves the "i5 questions" about using technology:

How would more information help students see the details and breadth of this topic?

How would images or nonlinguistic representations add meaning or context to the topic?

How would interacting with programs or other people provide clarifying and corrective feedback?

How would inquiry—a thinking skill—enrich the depth of a topic?

What innovative ideas could students produce?

One educator we worked with, Frank Korb, teaches about chiaroscuro art. While a textbook may provide a few paragraphs and images to explain the concept, Frank asks his students to search for information about the technique online, where they could view multiple sites—from museums to private collections—with related information and images. Students use digital devices to gain access to the volume of information and images that enrich interaction with peers and the teacher about the lesson's content. To process this inundation of knowledge, Frank's students learn to use inquiry, setting the stage for innovation. They use the knowledge they gained to push further in their thinking by creating their own art pieces or producing critiques to share with the class.

In an advanced Spanish course, to take another example, students might read a picaresque novel. They could learn to search online for information about the genre, including examining images from books, cinema, and other forms of art. Students may listen to podcasts or lectures by authors and critics; for inquiry, they might engage in problem solving about whether certain texts should be considered part of the genre.

When technology coach George Santos works with elementary teachers, he reminds them that students need to learn how to search for information. In addition to training teachers how to use programs, he employs the i5 Approach to help them ensure that the content of lessons will result in students becoming both technologically savvy and much better at gathering the right information, so they can create original ideas.

Teachers can plan for students to use digital platforms to gather large amounts of content about the lesson's topic; this enhances the students' ability to sort, anticipate, plan, predict, and evaluate. They will have plenty of declarative knowledge to "think about," opening doors to innovating.

Turning Students into Innovators

How can educators ensure that innovative teaching results in students being innovators? Students come to class actively seeking information and feedback. They need lessons planned and delivered in a slightly different way than in the past. When students have opportunities to regularly learn curricular content with effective strategies to enhance long-term retention, they become more engaged. By applying thinking skills as a springboard for creating, they naturally seek more information. Finally, they need to readily have access to large amounts of information in multi-sensory formats to make connections between existing knowledge and new possibilities.

Teachers, whether teaching in-person or remote, can have confidence that by making the few changes to lesson planning and delivery described here, their innovative lessons will also turn students into the innovators.

Key Strategies to Address Instructional Gaps

Implement skills-based, flexible groups in reading and math in addition to groups based on readiness.

Use morning work and homework as opportunities to address previous grade-level content that students didn't master.

Spiral previous grade-level content throughout the school year.

Plan in vertical teams at the end of the school year, at the beginning of the school year, and before planning new instructional units.

Reflect and Discuss

Do you think your students got more innovative while learning during the pandemic? Why or why not?

What's one small way you might rewrite a lesson plan to encourage innovative thinking in students?

How can teachers use technology in their teaching to broaden student thinking and learning, but not overwhelm them?