Just as the value of a library card depends on the number of books in the library, the value of a network depends on the number of users, computer systems, databases, and organizations already attached to the network. By almost any measure, the world's largest computer network is the Internet. The Internet evolved from a U.S. Defense Department communications system to become an interconnected collection of more than 46,000 independent networks, public and private, around the world (National Science Foundation 1995). Now serving millions of users worldwide, its growth is rapid and exponential.

For schools, an Internet connection presents some obstacles and many potential benefits. In 1993, the Pittsburgh Public Schools began such a program, in partnership with the Pittsburgh Supercomputer Center and the University of Pittsburgh, and with funding from the National Science Foundation. At that time, Carnegie Mellon University began a four-month project to aid the Pittsburgh Public Schools in their new endeavor, which was known as Common Knowledge Pittsburgh.

To observe the uses of the Internet in Pittsburgh, our research group surveyed and/or interviewed approximately 45 educators in various positions throughout the school system. Of that number, 24 teachers and 4 librarians from 4 schools attended a professional development workshop on Internet use in classrooms. Of the 28, 14 completed surveys about the effectiveness of that program. We also interviewed students.

In addition, we made numerous observations in one of the four schools participating in the first year of the project, an elementary school in a low-income area of Pittsburgh. A comparable number of school have come online each subsequent year (Carnegie Mellon University 1994).

To catalog what other teachers outside of Pittsburgh were doing with the Internet, we compiled responses from a questionnaire addressed to educators who use the Internet via relevant newsgroups and e-mail distribution lists. We received 21 responses describing 34 distinct classroom activities. Given the small sample size and a method of distributing questionnaires that naturally favors frequent Internet users, our statistics are not terribly meaningful. Our questionnaire was deliberately unstructured, however, to enable recipients to elaborate on their experiences and to share insights about the Internet. We also conducted unstructured interviews with educators who were using the Internet. To supplement these data, we studied descriptions from the printed literature of roughly 40 classroom activities.

How Students Are Using Computers

- [[[[[ **** LIST ITEM IGNORED **** ]]]]]

- File transfers (FTPs) allow a user to copy a file (which can contain text, software, pictures, and music) from, or to, another computer system. With a variation, anonymous FTP, a user can copy files without the need for password privileges.

- Telnet allows a user to log onto a remote computer as if it were in the same room. For example, one might telnet onto a system because it has capabilities that the local system lacks.

A number of important tools have also developed in recent years that facilitate the search for information on the Internet, such as Gopher, Archie, Veronica, Mosaic, and, more recently, Netscape. Obviously, such tools are useful only if the network contains useful information. (There is no way to describe all of the resources available on the Internet; the box on p. 22 gives five examples.)

- Students send their work to some other party for evaluation or response. The network provides a high-tech postal service, but with no cost per letter, minimal hassle, and most important, a negligible time for the message to reach its destination, which enables meaningful interaction. With pen pal programs, younger students write e-mail messages about themselves and their interests to peers in distant places. There is strong motivation for students to write good letters because, as one teacher put it, “A good letter writer generally receives good letters.” Older students exchange more complex material like stories and artwork, sometimes critiquing one another's work.Other programs provide a forum to learn about distant events and different ways of life. In one example, inner-city elementary school students corresponded with Native American peers who live on a reservation. E-mail is also sometimes written in a foreign language to both motivate and help students learning that language.The Internet makes possible communication between students and older students or professionals as well. Some students send their writing samples to professional writers for feedback; others correspond with professional engineers for help with independent science projects. Still other activities link handicapped students with big brothers and sisters, for example, or connect students from schools where few go on to college with their older counterparts who are in college.

- Group projects enable students at different locations to collaborate on activities. For example, students can cooperate on tasks like taking temperature and barometric measurements for a weather project or surveying garbage around their schools for an environmental project. Because many of these projects are experimental in nature, students engage in meaningful exploratory science with a large body of data. They gather information locally, and then pool data from around the world. Although they spend a relatively small amount of time collecting their part of the data, students understand how all of the data were collected, and have a sense of ownership. Other projects show students the value of working in groups, because each classroom is bound to produce ideas that improve the group's solution.

- Students exploit remote data sources and processing capabilities on the network. Most often, the Internet serves as an enormous library with extraordinary search capabilities. With the growing popularity of new browsing tools, such activities are likely to become more common. The Internet's remote processing capabilities can also be valuable. For example, students can run computationally intensive scientific simulations on a powerful remote computer that cannot be run on the school's inexpensive equipment. Such simulations can also replace expensive (or dangerous) laboratory equipment in the school.

Many educators told us that the Internet allows them to tap information sources on their discipline or on teaching in general, and to correspond with other educators around the world with similar interests. As one teacher said, “When I get the information I'm seeking, I can incorporate some of the activities in my lessons, also advancing my own professionalism.”

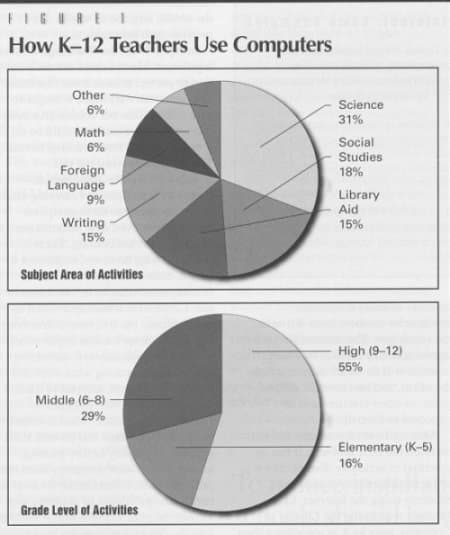

Figure 1 is a breakdown of activities described in responses to our questionnaire. Although these results are not statistically significant, they do dispel the myth that computers and networks are just for math and the sciences.

Figure 1. How K–12 Teachers Use Computers

How the Internet Benefits the Classroom

Two-thirds of the respondents to our questionnaire said that a primary benefit of the Internet is making students aware that they are part of a global community. Others commented that the Internet gives students a wide variety of resources, stimulates thinking, and improves computer literacy.

From our many observations in the inner-city elementary school in Pittsburgh, an important benefit of using this technology is enthusiasm. Whenever the Internet teacher walked into the room, students appeared hopeful that it would be their turn to use the Internet. Teachers even threatened to revoke a student's computer privileges as a punishment for disruptive behavior. As for teachers, their enthusiasm was unmistakable in both direct interviews and survey responses.

The Internet and other information technology in the classroom, of course, do much more than boost enthusiasm or expand information resources. Internet use fundamentally alters the roles of teachers and students. For example, when students write to impress a pen pal or a distant expert, the teacher is no longer the sole judge of quality, and grades are less of a motivating factor than in traditional classrooms. In addition, many activities require students to work in teams. When students spend class time browsing the Internet rather than listening to a teacher's lecture, they encounter more diverse expert opinions, work more independently, and proceed at their own pace. In fact, we observed that students experiencing computer problems were more likely to consult peers than the teacher. Throughout this process, the teacher becomes more of a facilitator, helping students find information and, more important, figure out what to do with it.

When parents have access to this technology at home or at work, they can become more closely involved in their children's education. For example, during parents' nights, students may be able to teach their parents something new about computers or networks. Doing so can greatly boost a student's self-esteem. Because familiarity with information technology can lead to jobs, schools may also want to expand their efforts to train neighborhood adults after school hours.

Many parents already have Internet access at work. Thirty-five percent of U.S. households now have computers, and those with children are more likely to have computers than those without, even families on a somewhat limited budget. Of households with children and total annual incomes under $30,000, 30 percent have computers. Given that consumer spending on home computers now exceeds spending on televisions, these percentages should continue to rise quickly (Negroponte 1995).

All it takes is a telephone line and a modem to connect a home computer to the network. More important, because there will always be parents without home computers, some states and municipalities are bringing network capabilities to all of their citizens. In Seattle, for example, even the homeless will be able to communicate over the network by getting an account from the city, and using it in libraries and other public buildings.

How to Overcome Difficulties

- Be specific about expectations and objectives. By providing deadlines for activities and for intermediate milestones, teachers can keep students moving in the right direction.

- Search the Internet yourself before asking students to. As one teacher said, “Know what to look for in advance, so you and your students will not be disappointed.”

- Allow ample time. “Realize that it will take twice as much time as you have budgeted,” suggested one teacher. Another offered, “Have students work in groups to speed up the process.”

- Establish a commitment with other parties involved in an activity. As one teacher urged, “There is nothing worse than getting a project organized or planning one into your lesson plans and then no mail arrives from your partners or people start dropping out.”

Teachers also identified three difficulties not entirely within their control. First, 40- to 50-minute class periods limit students' ability to engage in unstructured tasks. Allowing time for longer activities, therefore, may require creative structuring of the school day. Second, some teachers must overcome a lack of hardware, telephone lines, or accounts. Finally, lack of time for teachers to explore the Internet is a problem. The Internet's resources are vast, and the tools change from year to year. Keeping up is not easy. Things will improve when more principals and others understand the value of the Internet, and the importance of teacher time spent exploring it.

Probably the most disturbing problem came out in direct interviews with teachers who were not part of the Pittsburgh project. Not only are rewards for innovative teachers often small, but some principals and teachers actually discourage resourceful teachers from disrupting the status quo. The reasons for such opposition may include two fears: that benefits will be small and not worth the effort, and that benefits will be great, so other teachers will be expected to keep up.

Although our respondents did not mention the next problem, it has the potential to seriously disrupt efforts to bring the Internet to classrooms. Students using the Internet, like students wandering the Library of Congress, may look at something their parents would prefer they not see—for example, sexually explicit material. Topics like drugs, politics, religion, abortion, and homosexuality may also stir controversy.

In June 1995, the U.S. Senate attempted to address a part of this problem by approving an amendment to the telecommunications bill that would prohibit the flow of “indecent” material (not limited to pornography) on the Internet. Aside from the serious civil rights implications of such censorship, it would not even prevent the distribution of pornography on this network of millions of users around the world, any one of whom can provide such information.

In April 1995, the Washington State legislature found a more drastic solution to protect minors from objectionable material: they made it illegal to give minors Internet access. (An even more effective solution would be to prohibit minors from learning to read.) The governor vetoed the bill.

Schools can take some precautions—for example, not carrying obviously troublesome newsgroups on local servers. And new information-filtering tools are coming. There is really no way, however, to prevent a bright, determined student from finding something he or she wants to see. Constant teacher supervision is one solution, but it is time-consuming and would deter curious exploration.

The best approach is to develop a written policy stating what does and does not constitute acceptable student usage of the Internet. In general, Internet usage should relate to coursework. Both students and parents must agree to this policy before gaining access. While such a strategy does not prevent abuse, it does make it easier to revoke the privileges of students who violate the policy, and it brings parents into the discussion from the beginning.

About Teacher Preparation and Support

Before adopting the Internet, a school system must determine how much preparation and ongoing support to provide. Two-thirds of the respondents to our questionnaire survived without any formal training, relying instead on printed literature and experimentation, or as one person described it, “blood, sweat, and tears.”

Common Knowledge Pittsburgh developed a professional development workshop for teachers and librarians that participants generally found quite successful. The primary goal was to give them the problem-solving skills to become explorers of the Internet, rather than teaching them facts or rote methods. Because Internet tools and resources are constantly changing, teachers must have the ability to adapt—a view echoed by several respondents to our questionnaire.

The workshop, held in June 1993, provided 24 teachers and 4 librarians with 13 hours of instruction over two and a half days. Participants worked in pairs to promote brainstorming and to make the task less intimidating. They used a variety of tools ranging from newsgroups to Gopher, and explored resources that workshop organizers thought might be useful, like the NASA library (see box, p. 22). To test their newfound skills, they participated in a scavenger hunt for information on the Internet.

After this session, workshop organizers helped participants set up borrowed school computer equipment in their own homes to experiment during the summer. Finally, the workshop reconvened in August for 10 hours of additional instruction over a two-day period. In addition to learning more about the Internet, participants discussed possible lesson plans.

As noted earlier, 14 workshop participants responded to our survey. Every respondent agreed that the teaching methods were effective; only one person did not yet feel capable of teaching the Internet to students, with two people unsure. All found the workshop informative, and almost all would recommend it to a colleague.

Because a primary goal of this workshop was to encourage exploration, that issue deserves special consideration. After a few months into the school year, nearly half of the participants had done three or more Gopher searches in the week we surveyed them, but two people indicated that they were no longer exploring the Internet. Despite the popularity of the workshop, participants indicated that they learned only about half of the information on the Internet from workshop instructors. That finding would seem to corroborate the importance of independent exploration.

How would the Pittsburgh educators improve the workshop? They were about evenly split on the need for more step-by-step instruction time, but expressed a pressing need for more exploration time.

Because one can't afford to stop learning about the Internet, ongoing support may also be important. In answer to the questionnaire we sent to network users around the world, teachers indicated that Internet guides, newsgroups, and distribution lists are very helpful. Personal support is also needed at times.

In Pittsburgh, teachers turned to their fellow teachers most often, with the centralized support staff a close second. This finding is important because widescale adoption is possible only if teachers help one another; a centralized support staff can't be everywhere.

When asked about other kinds of ongoing technical assistance, teachers who responded to the questionnaire most often mentioned classroom visits by Internet instructors, monthly meetings of Internet users, and online support.

The Future

Teachers have only begun to exploit existing capabilities of network technology in schools. Indeed, the majority of classroom activities that we've observed use only Internet tools that are more than two decades old, like basic e-mail. As noted, tools such as Mosaic and Netscape greatly facilitate the process of finding information on the Internet.

People are also experimenting with more interactive applications. For example, the Internet has been used for person-to-person video teleconferences, and to broadcast part of a Rolling Stones concert live.

Moreover, new networks are coming based on ATM (asynchronous transfer mode) technology. Although such things are possible to a limited degree on the Internet, ATM networks are better able to support applications where intermittent disruptions are noticeable to the user, like using a telephone, playing interactive games with a distant player, or controlling a laboratory experiment at a remote site. ATM networks can also transmit data at a rapid rate, allowing users to watch broadcast-quality video or better on demand, to quickly retrieve a series of images from the space shuttle's telescope or the complete works of Shakespeare, or to use sophisticated visualization tools to watch changing weather patterns in the area. Recently, North Carolina deployed a statewide ATM network to which schools will have access.

Although the growth of Internet use in classrooms is encouraging, schools have not been keeping up with any of the commercial sectors in adopting new information technology—so it is not clear whether technical advances alone will be beneficial for learning. An obvious obstacle is money. However, 97 percent of American schools already have some computers (Wheland 1995), and adding a low-speed Internet connection is no more expensive than adding a telephone line. Still, many of these computers are not integrated into the curriculum in a meaningful way, other than one designed specifically to teach about computers. While funding is certainly an issue—and more conclusive proof is needed that money spent on Internet access is more beneficial than money spent elsewhere—increased funding alone is unlikely to lead to productive use of information technology.

To truly exploit these advances, technology and innovation must permeate the culture of education. Teachers should be exposed to technology early in their careers, and should be actively encouraged to keep up on continual advances. To reduce installation costs, new schools should be wired for computers and networks when they are built, just as commercial office spaces are. Districts should hire staff who can help schools build and troubleshoot computer and network systems. Teachers must be given freedom and encouragement to experiment with technology.

Common Knowledge Pittsburgh, now operating in 14 schools, is currently funded through December 1997. The Pittsburgh Public Schools are showing that more teachers will choose to bring technology into the classroom when given both resources and encouragement.