Young people, increasingly, are leading protests and engaging in advocacy for their generation and their communities. Think of the March for Our Lives, organized by students who survived the Parkland school shooting, or Greta Thunberg, the 16-year-old climate activist who started a worldwide movement to demand policy change (and was named Time's 2019 Person of the Year). On the world stage, youth are using their voices to effect change. Shouldn't we also listen to them in our schools?

When designing a plan to transform a low-performing high school in our city, we built student empowerment into its foundation. The stakes were high. We faced both the pressure to prevent the school from closing and the opportunity to reshape it into a place that truly served young people and expanded their opportunities for advocacy.

Too often, however, schools position their scholars as passive recipients of knowledge, expected to follow the rules, stay out of trouble, and keep their curiosity carefully bounded. Changing schools and narrowing the achievement gap are nearly impossible in a climate of student and teacher boredom and frustration with such expectations (Sylvester & Summers, 2012). Particularly in urban contexts, where schools have implemented oppressive practices that focus on standardized testing and punitive behavioral measures, student voice is sometimes unwelcome and even silenced.

These were the potential pitfalls for East High School, the oldest, largest, lowest-performing school in Rochester, the lowest-performing district in New York State. In 2014, after years of failing to meet progress benchmarks, East was headed toward a forced closure. During that year, the graduation rate was 33 percent; there were 2,468 suspensions; and average daily attendance was 77 percent. In an effort to prevent East from closing, the Rochester City School District took advantage of a new reform option offered by the state, in which a school forms an Educational Partnership Organization (EPO) with a "receiver." After a series of conversations, the University of Rochester was granted a five-year contract to lead this partnership.

Students at the Center

As a university researcher (Valerie) and East's superintendent (Shaun), we represent the theory-to-practice relationship of the receivership. From creation to ongoing implementation, we built scholar voice into our EPO plan. A student survey, taken a year prior, revealed that our scholars felt unheard in the school's decision making and that they desired agency. In response, our plan specified that scholars would sit "squarely at the center of the schooling experience. [They] will learn to take charge of the learning and gradually to take leadership roles both within the school and community."

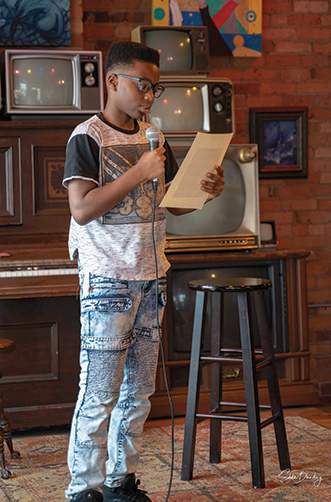

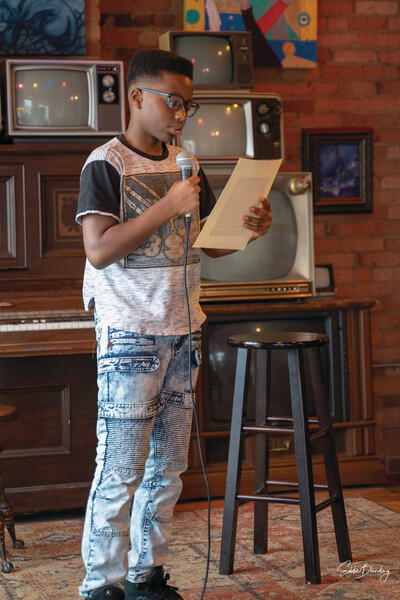

As part of a reading and writing workshop, 8th grader Jai'quielo Madison performs his original poetry at a local coffee house. Photo by Eddine Blanding.

This vision was based on theories of positive youth development and asset-based theories of youth (Morrell, 2008; Paris & Alim, 2014). These theories suggest a recentering of pedagogy and curricula around youth—their histories, cultural competencies, and interests—as a socially just, equitable approach to learning. Our plan expected scholars to participate as active, informed citizens, and our design provided them opportunities to develop leadership qualities.

The mission statement that we ultimately adopted, with input from both students and staff, supports this endeavor: At East we are taking charge of our future by being tenacious, thinking purposefully, and advocating for self and others. That last part—"advocating for self and others"—reflects our commitment to a culture where scholars believe their voices are welcome. With their participation in creating the mission, students bought in to living out the mission.

When Theory Meets Practice

Of course, intention and reality often exist in friction, especially with young people. We learned this early on. In our first school assembly after the transition, we announced to students that they would be required to wear school uniforms: a notably ironic administrative decision given our priority on student self-advocacy. Even in schools that intend to support student voice, educators can lapse into practices that impose arbitrary structures that silence them. Perhaps unsurprisingly, the 400 students in the auditorium booed us. "I thought there was going to be a riot," said Assistant Principal Shalonda Garfield. "But I noticed that our principal just stood there. And listened. And let them boo. And as a new administrator, I was thinking, what's about to happen? She gave them a few minutes. They stopped booing. And we talked about it." A year later, the school uniform requirement was reversed. What happened between that first assembly and the decision to change the policy?

Over the course of the intervening year, the conversation that began in the assembly continued. Our scholars made their voices heard through various avenues: meetings with our school principal, participation in East's Governance Council (a school-based planning team), town hall meetings, and advisory period. They advocated and even protested by showing up without their uniforms. "We need to be able to express our identity," our students told us. A tension arose between our policy, our practices, and our beliefs. If we truly wanted to foster student agency, we knew we had to change our policy to ensure that our actions and beliefs aligned.

A Family Affair

How else did we listen to our students? With our new, extended school day (an additional EPO-mandated hour), we built time in the schedule for "Family Group," a 30-minute, daily period where groups of 10 scholars meet with two teachers. Every scholar and every adult in the building belongs to a Family Group. The structure provides time and space for teachers and scholars, who typically interact around academics, to build more personal, supportive connections to each other. Family Groups are fertile environments to learn about self-advocacy.

During these meetings, we introduce and practice restorative tools like circling and using a talking piece. East Social Worker Eddie Blanding explains how these tools facilitate youth agency: "When I have the talking piece, you're invited to listen and I'm invited to speak. And that helps the person who's lost in the circle, who's normally lost in the classroom even, who doesn't really talk but has things [to say]. It gives them an opportunity to have a voice, too."

These practices also help students navigate personal conflicts. "If I have a problem with somebody, I know what I can do," says Gabriella (a pseudonym), a high school senior and student leader. "I can gather them around with people from the school—like an administrator—and we could just talk. We could have a 'Family Group circle' as we call it here." Over the past several years, Gabriella has gained confidence that she can, in fact, influence her school experience.

We believe that Family Groups and restorative practices have been the source of a student behavior turnaround. Now that students can rely on safe spaces and practical tools to proactively address conflict, behavior has improved dramatically. Since 2014, suspensions and disciplinary incidents have each fallen by nearly 80 percent (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. East Behavioral Disciplinary Data

How Student Voice Transformed East High-table

School Year | Incidents | Short-Term Suspensions | Long-Term Suspensions | In School Suspensions | Out of School Suspensions | In Alt. Program | Total Suspensions |

|---|

| 2014–15 | 1,629 | 2,374 | 94 | 1,423 | 968 | 77 | 2,468 |

| 2018–19 | 332 | 465 | 21 | 398 | 68 | 20 | 486 |

In Family Group, the agenda is co-constructed by adults and scholars. Blanding says these relationships help to humanize teachers and adults. Prior to the EPO, behaviors that would be considered disrespectful toward an adult (cursing, yelling, throwing things) or disrespectful adult behaviors toward scholars (dismissiveness, deficit thinking, abuse of power) were not uncommon occurrences. But "it's different when you know that teacher is a person," says Blanding. "So it's equal playing ground in the Family Group. It's not like, 'we're the adults and you're the student.'" Likewise, adults have begun to realize that not only do they support scholars in Family Group, but scholars support each other and sometimes the adults. As Principal Marlene Blocker notes, Family Group time is "really an opportunity for every person to grow and be nurtured. And some people originally thought the purpose was for scholars, but what I find is that what our scholars give back to us has been just as beneficial."

Town Hall Gatherings

Another structure that East built into the school schedule takes the form of town hall meetings—grade-level assemblies that meet weekly during the Family Group period. Scholars set the agenda and lead the conversation. Town halls are an opportunity to shape and revisit norms that maintain a positive culture in the building, to recognize scholar progress on things like attendance or rising graduation rates, and to make announcements. Increasingly, they have also become a forum for student voice.

It was during a town hall that Gabriella and her classmates proposed establishing new opportunities for the high school seniors. With the administrators and counselors listening, scholars shared that senior year was important to them and that seniors deserved special privileges. The class successfully advocated for a movie day just for seniors, as well as a senior lunchroom and off-campus lunch privileges.

During another town hall meeting, student leaders raised concerns about the LGBTQ community at East. They had been learning that LGBTQ youth get bullied at significantly higher rates than their peers and experience higher rates of suicide and homelessness. At the same time, students at East who identify as LGBTQ voiced concerns (to select, trusted teachers) about their lack of representation in student decision making. Together, they proposed organizing a Coming Out Day, to coincide with the national event, so that East's LGBTQ students could feel a sense of belonging among the wider school community. They asked their teachers who identify as LGBTQ to participate by sharing their experiences. The Coming Out Day event was so heavily attended by scholars and staff that, according to Gabriella, "There were people outside of the senior lounge waiting to go in. Kids wanted to go and hear stories." With the town hall structure, students' ideas are taken up and taken seriously, often resulting in action.

Perhaps most powerfully, the EPO plan accounted for greater scholar agency in academics. When rewriting the curriculum, one of our goals was to embed performance tasks—scholar-created products or presentations to audiences beyond school walls. While creating these performance tasks, teachers and scholars think about ways they can authentically engage with the community. For example, scholars who are part of reading and writing workshop classes present their original fiction and poetry at a local coffee house with parents, fellow scholars, teachers, and community members in attendance. Following these events, scholars can't wait to perform again.

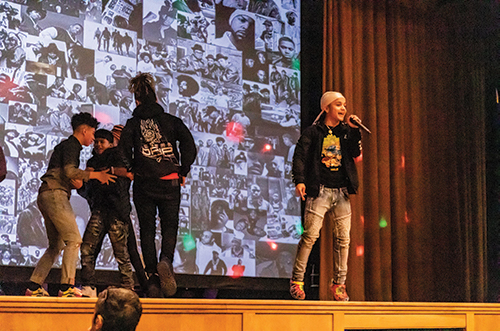

Some scholars in the older grades also voiced a desire to take courses that were more culturally relevant, contemporary, and engaging. In response, a university researcher, in partnership with an East teacher, worked with a group of students to develop a hip-hop literacy course and embedded a performance task into the design. Scholars led the lessons and activities, partnering with local resident artists, and produced an assembly that taught the origins of hip-hop, described its influence on world culture, and featured original student performances. The class was so popular that it is now part of East's regular course offerings.

East Upper School students share their talents at an annual school hip-hop showcase. The students transform their life stories into powerful works of art that they perform, using hip-hop as a vehicle for expression and literacy development. Photo by Laura Brophy, University of Rochester.

Latino Club students give a special holiday performance–a Parranda (Puerto-Rican style caroling)–to senior citizens at the Ibero-American Action League's Centro de Oro. Photo by Laura Brophy, University of Rochester.

"Every Single Day"

As we draw near the end of the fifth year of our university-school partnership, we are seeing encouraging signs. As scholars have become increasingly involved in school decision making, we have noticed not only a decrease in disciplinary incidents, but also an improvement in academic markers. As of last year, attendance has risen nearly 10 percent and the graduation rate has more than doubled (from 33 percent to 70 percent). This spring, we anticipate that East will reach its highest graduation rate in 20 years.

East scholars have learned, as time passes, that their voices really are welcome and can influence their school in ways that matter to them. Teachers have learned that student contribution is not just good for scholars, but valuable to the school community. When scholars feel agentic and cared for, they respond to teachers more positively. To use social worker Eddie Blanding's words, "they see them as people." This dynamic encourages teachers to continue to listen and support student agency—in academics, relationships, and school activities. In turn, scholars recognize themselves as capable and worthy.

"As a scholar, I can go to any teacher," Gabriella notes. "I can go to an administrator. I can go to the principal. She's not gonna say 'I don't have time for you.' She's gonna say, 'Do you want to come to my office? Do you want to make an appointment?' … My voice is heard every single day."

Reflect & Discuss

➛ Conduct a student voice "audit." What current opportunities do your students have to influence schoolwide decision making?

➛ What new structures could you build into your school or classroom to invite student voice?

➛ When you get student input, do you typically act on it? If not, how could you close the gap?