A rubric is an evaluation tool consisting of a set of criteria, a fixed scale (e.g., 4-point, 7-point), and descriptors that distinguish the differences in the levels of the scale (Arter & McTighe, 2001). The term has its origins in the Latin word rubrica meaning "red earth" or colored soil used to mark things of importance. The term also references the large, red opening word in biblical manuscripts, indicating the text that follows deserves attention. Today, these meanings persist, since a well-crafted rubric signals to students the qualities that are most important in their work.

Rubrics are typically used by teachers to judge the degree of students' understanding, proficiency levels of skills, the quality of their products or performances, and their growth from one level to the next. But beyond being evaluation tools, rubrics can be an excellent way to give feedback for improving teaching and learning. Well-crafted rubrics provide a shared language that lets teachers and students work together to navigate the most important attributes of deep learning and effective performance.

Three types of rubrics are commonly used in schools:

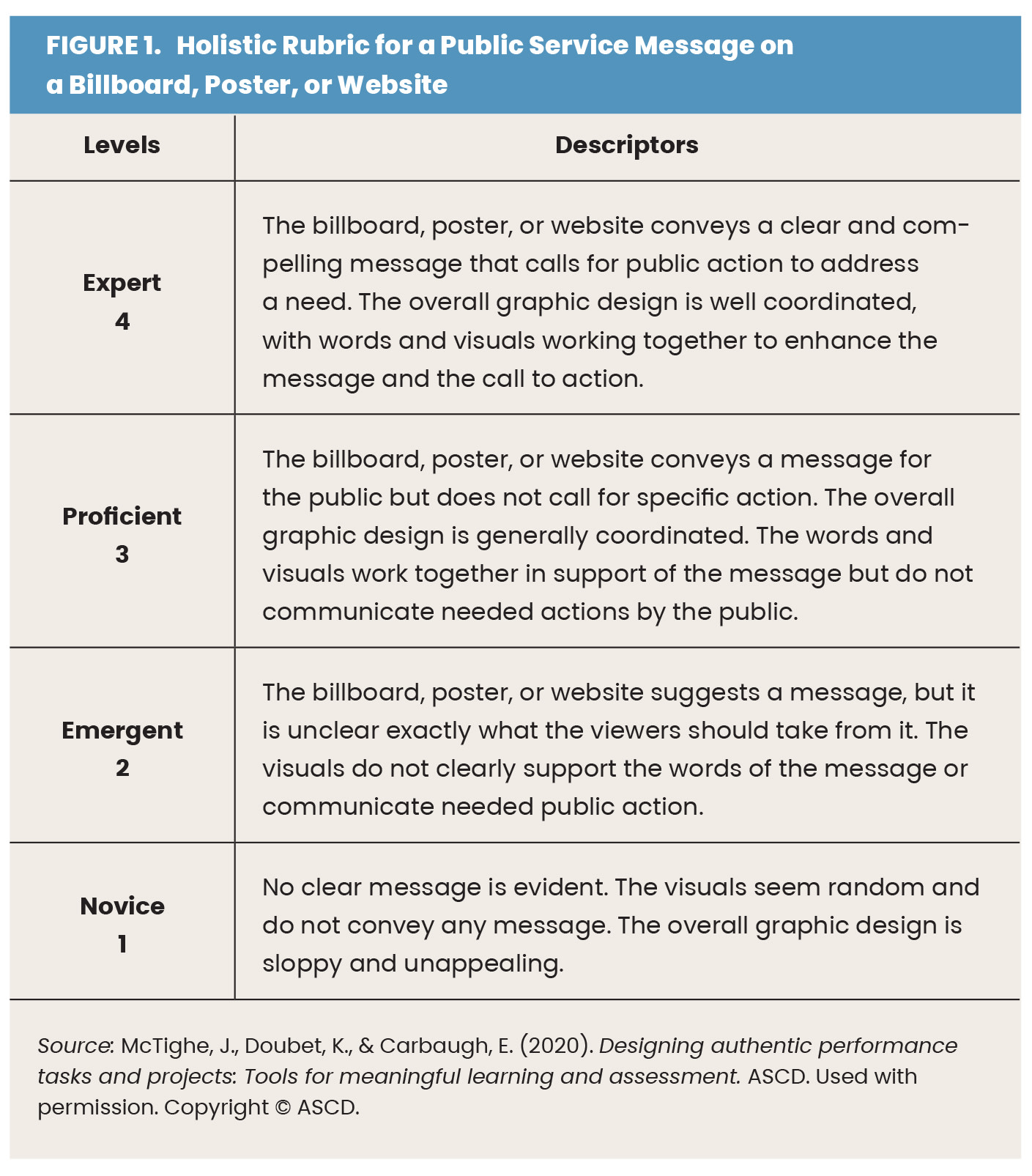

A holistic rubric provides an overall impression of a student's performance, yielding a single rating or score. Figure 1 shows a holistic rubric for a project asking students to create a public service message (McTighe, Doubet, & Carbaugh, 2020). Holistic rubrics gauge the overall quality or impact of a student's work; for example, to what extent did the story entertain its readers or to what extent was the argument convincing?

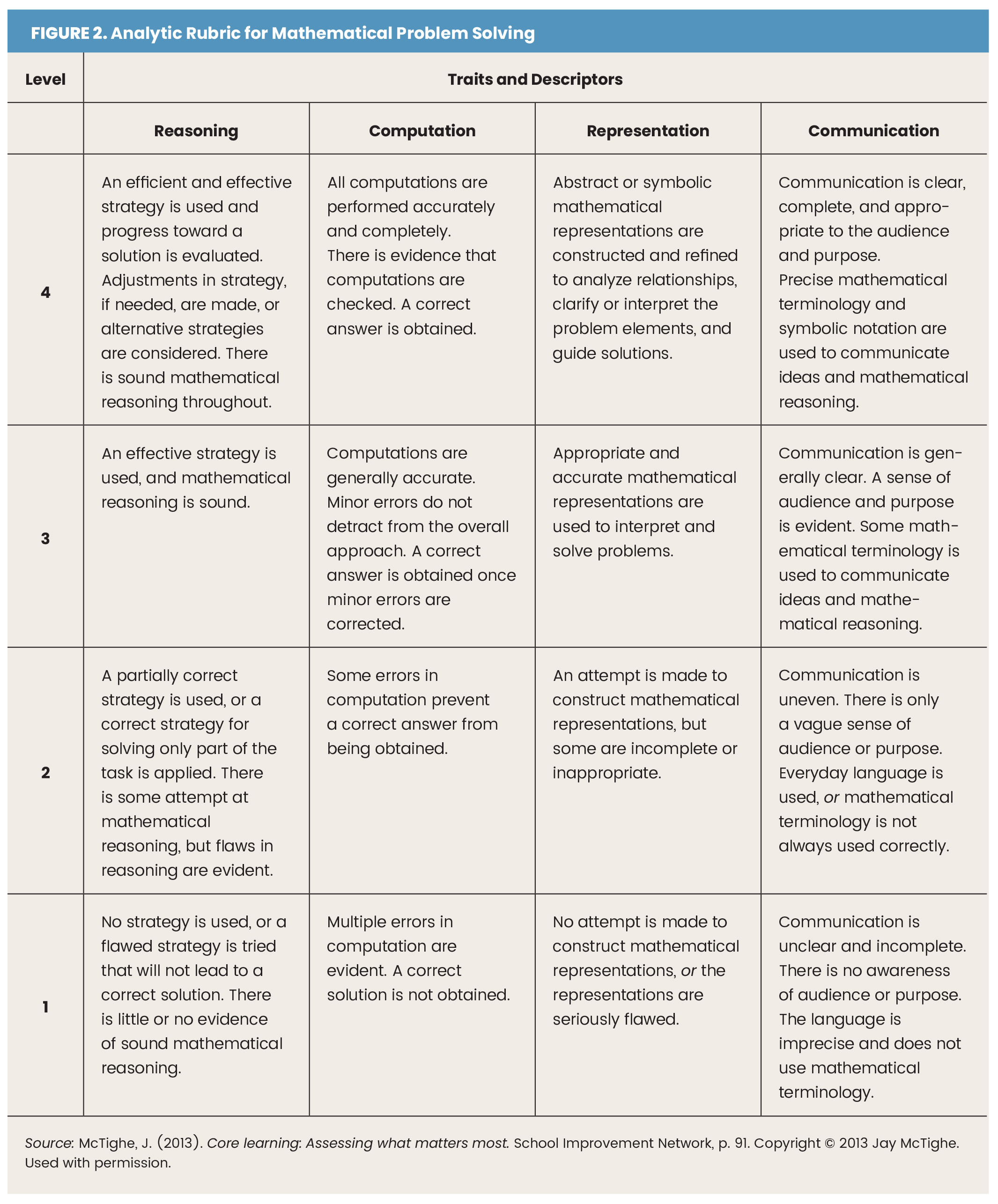

An analytic rubric also contains a performance scale but divides a targeted product or performance into distinct elements or traits and judges each independently. Figure 2 shows an analytic rubric for mathematical problem solving.

A developmental rubric describes growth along a proficiency continuum, ranging from novice to expert. Think of the six different colored belts in karate that designate various proficiency levels. Developmental rubrics are well suited to subjects that emphasize skill development over time, such as physical education or world languages.

What Makes a High-Quality Rubric?

An effective rubric is grounded by clear and appropriate criteria that serve as the basis for judging student responses, products, or performances. In essence, the criteria specify what "success" looks like. In a standards-based system, the criteria should be derived primarily from the targeted standards or outcomes being assessed, rather than from any specific assignment or assessment task. For example, if a teacher is focusing on expository writing, the rubric's criteria for any such writing task would target accuracy (information presented is correct and appropriate descriptive vocabulary is used); completeness (all relevant aspects of the topic are addressed); clarity (precise, well-chosen, academic vocabulary is used to suit audience and purpose; organization (information is logically framed and sequenced); and conventions (proper punctuation, capitalization, spelling; etc. is used).

When a high-quality rubric is used effectively, teachers and learners benefit. For teachers, good rubrics:

Specify the salient qualities of successful performance, based on targeted standards.

Support sound evaluation by describing important distinctions in the degree of understanding, proficiency, or quality from one level to the next.

Serve as teaching targets, since they reflect the qualities embedded in standards.

Provide feedback to teachers on how their instruction might need to be adjusted.

For students, high-quality rubrics:

Serve as learning targets, since they identify the key qualities of successful learning and performance.

Communicate how their work will be judged, presenting important distinctions in the degree of understanding, proficiency, or quality from one level to the next.

Enable them to self-assess their work and performance based on the success criteria.

Provide feedback that affirms areas of strength and informs needed improvements.

Leveraging Rubrics to Provide Effective Feedback

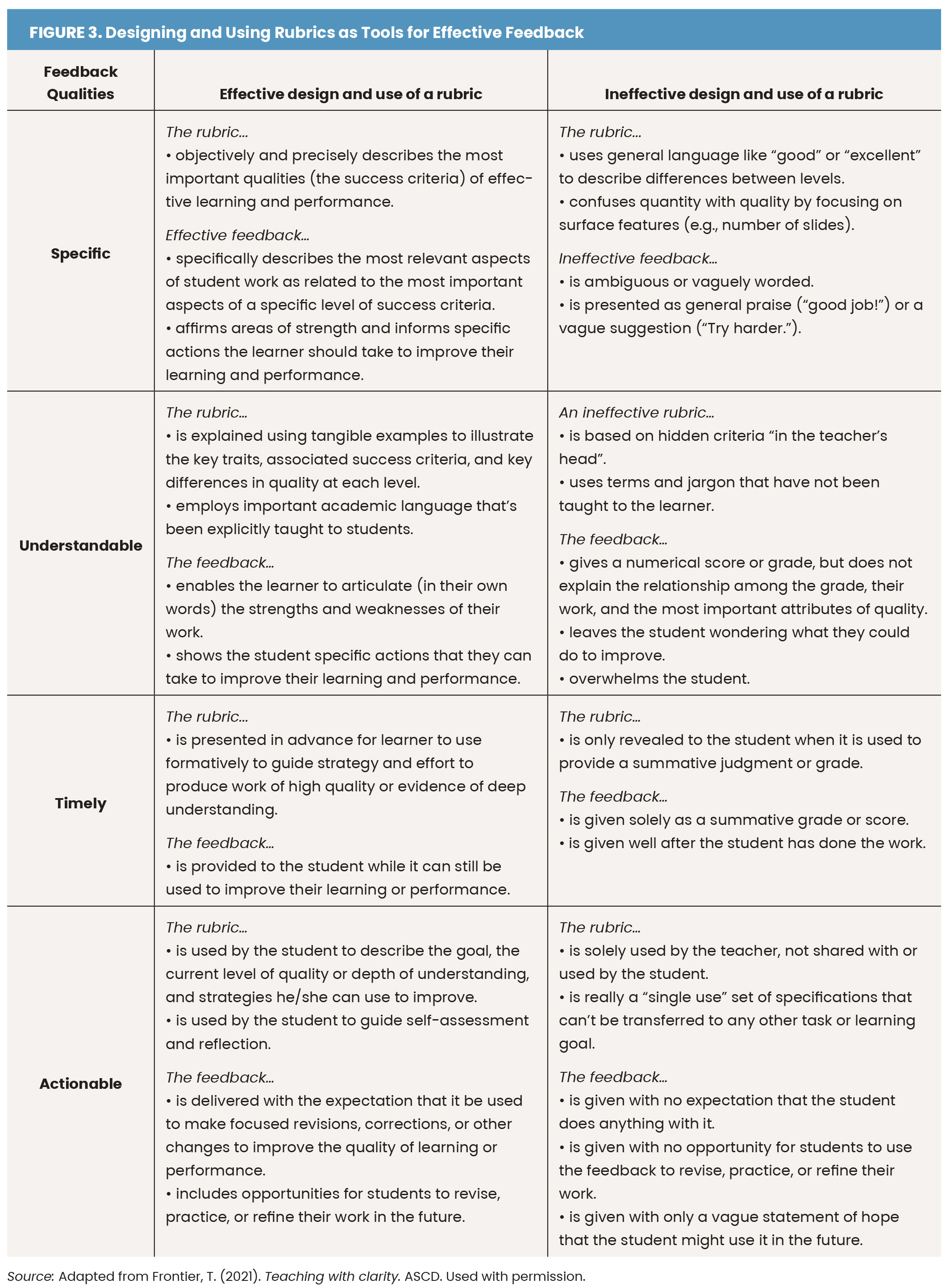

Feedback is descriptive information that's used to affirm areas of strength in learning and performance and point to areas needing improvement (Frontier, 2021). Grant Wiggins (2012) argued that to be most effective, feedback must provide information that is specific, understandable, timely, and actionable. A well-constructed rubric can provide the basis for specific feedback that is understandable to the learner, ensuring the learner knows exactly what they have done well and what they need to do next to improve. Timely and actionable describe how the rubric should be used if we want students to receive feedback in the manner we intend—to guide their next efforts toward deeper learning and improved performance.

Holistic rubrics are appropriate when a rubric's primary purpose is to assign a grade for an assignment or summative assessment task. However, a letter grade or a numerical score, on their own, don't provide feedback. How can students improve their writing skills, for instance, if all they receive is a "3" (or a "B–") on a holistic rubric for their essay? Without more detailed information, learners are left to guess what to do differently on their next essay.

Clarifying Rubrics

To help students understand a rubric's relevant language, teachers should explicitly teach key vocabulary contained in standards and associated rubric criteria.

Accordingly, we strongly recommend using analytic rubrics as feedback tools. Since they identify and evaluate distinct traits important to effective performance, analytic rubrics provide more detailed, targeted feedback to students about the strengths of their performance and areas needing attention. Analytic rubrics can also provide valuable feedback to teachers. For example, if a teacher notices a high percentage of students are showing weakness on a particular trait, that information suggests the need for greater instructional emphasis on that dimension of performance. Since there are several traits to consider, using an analytic scoring rubric may take a bit more time than assigning a single score. But we believe that the more specific feedback that results is well worth the effort.

Figure 3 summarizes key "do's and don'ts" for constructing and using rubrics in a manner that meets Wiggins' criteria for effective feedback.

Guiding Students to Use Feedback from Rubrics

Presenting students with a well-developed rubric and reviewing it with them is necessary, but not sufficient, to guarantee that students will get the most benefit possible from that feedback. Research on how feedback is used by those who receive it notes that "the ability to receive feedback well is not an inborn trait, but a skill that can be cultivated" (Stone & Heen, 2014, p. 8). In other words, students need to be taught the meaning of rubrics and how feedback works if we expect them to highly benefit.

For instance, to help students understand a rubric's relevant language, explicitly teach key vocabulary contained in standards and associated rubrics. If explanation or justification appear frequently in your priority standards and success criteria, for example, these terms should be highlighted as learning goals and included in vocabulary lessons and assessments.

One method we highly recommend is using examples of student work—anonymous samples from previous classes or ones you've created—to make more concrete the often-abstract criteria in rubrics and bring feedback to life. Teachers might:

Show students one or two examples of high-quality work, highlighting how the success criteria are evident within them. Highlight specific traits that are most important to the targeted standard. Then show several more samples and ask students to identify where they see the success criteria appearing in each.

To help students identify distinctions among the different performance levels described in rubrics, use a set of anonymous student work samples that range in quality. Present the diverse examples and ask students to rank order them into three or four sets and to give a rationale for their placements by describing the differences they see between the sets, using the language of the success criteria.

To help learners see how to use rubric criteria and level descriptors as feedback, ask students to identify specific ways that lower-level examples could be improved. Model this process through a "think aloud" to get students started.

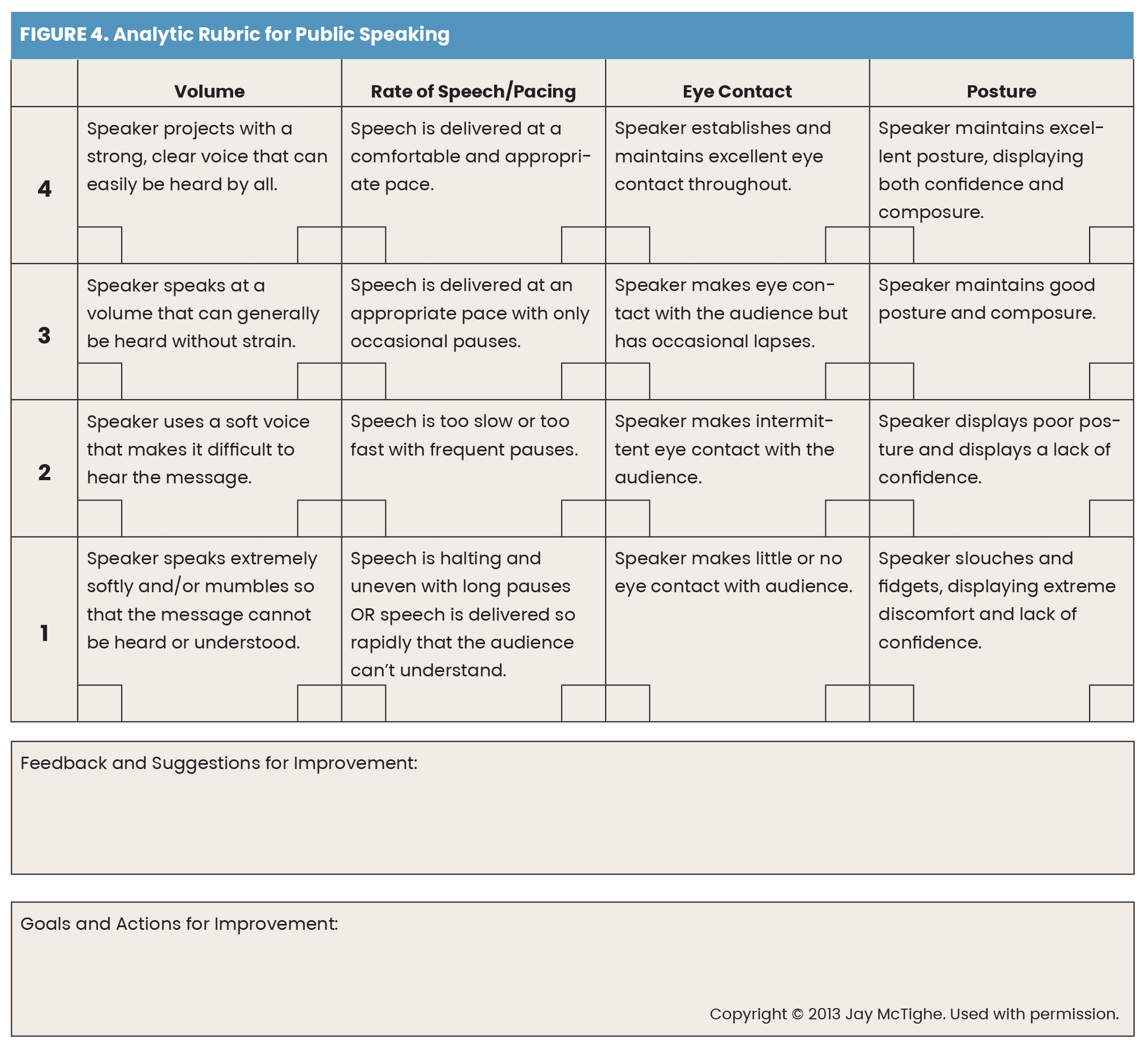

Another good practice is to teach students how to use success criteria from a rubric to self-assess and set future learning goals. This practice is based on the recognition that the most effective learners are metacognitive—they self-assess their performance, welcome and use feedback, learn from their mistakes, and set goals to improve their performance (Wiggins & McTighe, 2004). Two simple graphic additions to a rubric, illustrated in Figure 4, can support the cultivation of these learning habits (McTighe, 2013). The first is the inclusion of two tiny check boxes at the bottom of each cell of an analytic rubric. The student uses the check boxes on the left to self-assess their work before they turn it in. The teacher uses the other box for his or her evaluation. Ideally, the two judgments should match. Any discrepancy raises an opportunity to discuss the success criteria in relation to a student's work.

The bottom of the rubric includes a section for feedback comments (from the teacher or peers) and a space for the student to identify learning goals and action steps to improve their performance, based on external feedback and self-assessment. These minor additions turn an evaluation instrument into a tool for feedback, self-assessment, and goal setting.

Of course, teachers will need to explicitly teach students how to self-assess their work against criteria and model how to set improvement goals. But imagine the impact if every K–12 teacher, across subject areas, embraced this practice and encouraged their students to regularly self-assess and identify specific action goals!

A Shared Road Map

Well-crafted rubrics can serve as a shared road map for teaching and learning. They mark the most important routes for teachers and students to navigate as they walk the circuitous path to deeper learning and more effective performances. When educators use those rubrics to teach students how to discuss and describe that terrain, rubrics become the basis for the specific, understandable language of feedback—which students can leverage to guide their next steps to improvement.

Reflect and Discuss

➛ Do rubrics function effectively as a feedback tool in your classroom or school? Why or why not?

➛ Based on the criteria McTighe and Frontier discuss, in what ways could you improve the design and clarity of your analytic rubrics?

➛ What steps could you take to help students better understand and use rubrics for assignments?

Teaching with Clarity

Tony Frontier's book guides educators on how to simplify teacher practice and sharpen student learning.