After decades of talk about preparing our students for a job market requiring higher levels of cognitive, academic, technical, and personal skills, high schools today are still consigning many graduates to a lifetime in America's economic margins. Data consistently show that the typical high school prepares too many students for the one-third of jobs that require the most basic high school education (or less), and too few students for the two-thirds that require an advanced certification or postsecondary degree (SREB, 2020).

The economy has changed, the way we do work has changed—but in many secondary schools, the practice of labeling and sorting students has changed very little. Many students remain stuck in the shallow end of the middle and high school curriculum—wading through low-level academic and career-pathway courses with many links to low-paying careers or jobs that simply no longer exist.

To change this dynamic, education leaders and policymakers need to transform high school practices so that 95 percent of students will be engaged and challenged to move out of the shallow end of the curriculum and into deeper learning experiences. This transformation will require that high schools adopt a college-ready curriculum with intellectually demanding career-pathway courses and that teachers in those schools provide higher-level cognitive assignments in both career-pathway and academic classes. This kind of change is already happening in some high schools connected with the School Improvement Network supported by the Southern Regional Education Board (SREB) and in other U.S. schools that align learning in traditional academic courses with skills development in career and technical education classes. Such schools have created work in most courses that demands critical thinking and problem solving as well as technical know-how. But this transformation needs to spread.

The typical high school prepares too many students for the one-third of jobs that require the most basic high school education, and too few for the two-thirds that require an advanced certification or postsecondary degree

Building Career-Path Curricula

As former long-time senior vice president of the SREB (a compact of 16 states working together to improve public education), I, along with my colleagues, have devoted decades to helping schools adopt curricula that offer career pathways featuring rigorous academic and career-technical education courses. By career pathways, I mean a program of studies that provides students access to a coherent sequence of three or four career and technical courses in broad career fields connected to college-preparatory courses for all students. Rather than isolating CTE instruction in silos, such programs bring more CTE students into career-pathway courses connected to postsecondary studies and middle-class earning opportunities. Specifically, SREB's work in this area helps schools:

Revise assignments in existing career-pathway courses, design new ones, and adopt new career-pathway coursework to engage teams of students in using a mix of academic, technical, personal, and cognitive skills to complete real-world assignments.

Help math teachers adopt or design lessons that engage students in applying college-readiness-level mathematics concepts and skills to solve abstract and real-world problems requiring multiple steps.

Prepare career-pathway and academic teachers to design literacy-based assignments that engage students in reading complex technical and college-readiness-level content and have students show resulting understandings through written products.

These types of shifts recognize that to obtain a good job in today's economy, employees need a combination of academic, technical, technological, and workplace skills. Business and industry leaders seek employees who can work on teams, communicate with colleagues, understand and analyze complicated data, and apply literacy and mathematical skills to solve complex problems (Gray & Koncz, 2017).

At the Center for Advanced Technical Studies, a student assembles a home-made photovoltaic panel for a solar energy project. (Photo courtesy of Patrick Smallwood)

Rigorous, Real-World Assignments

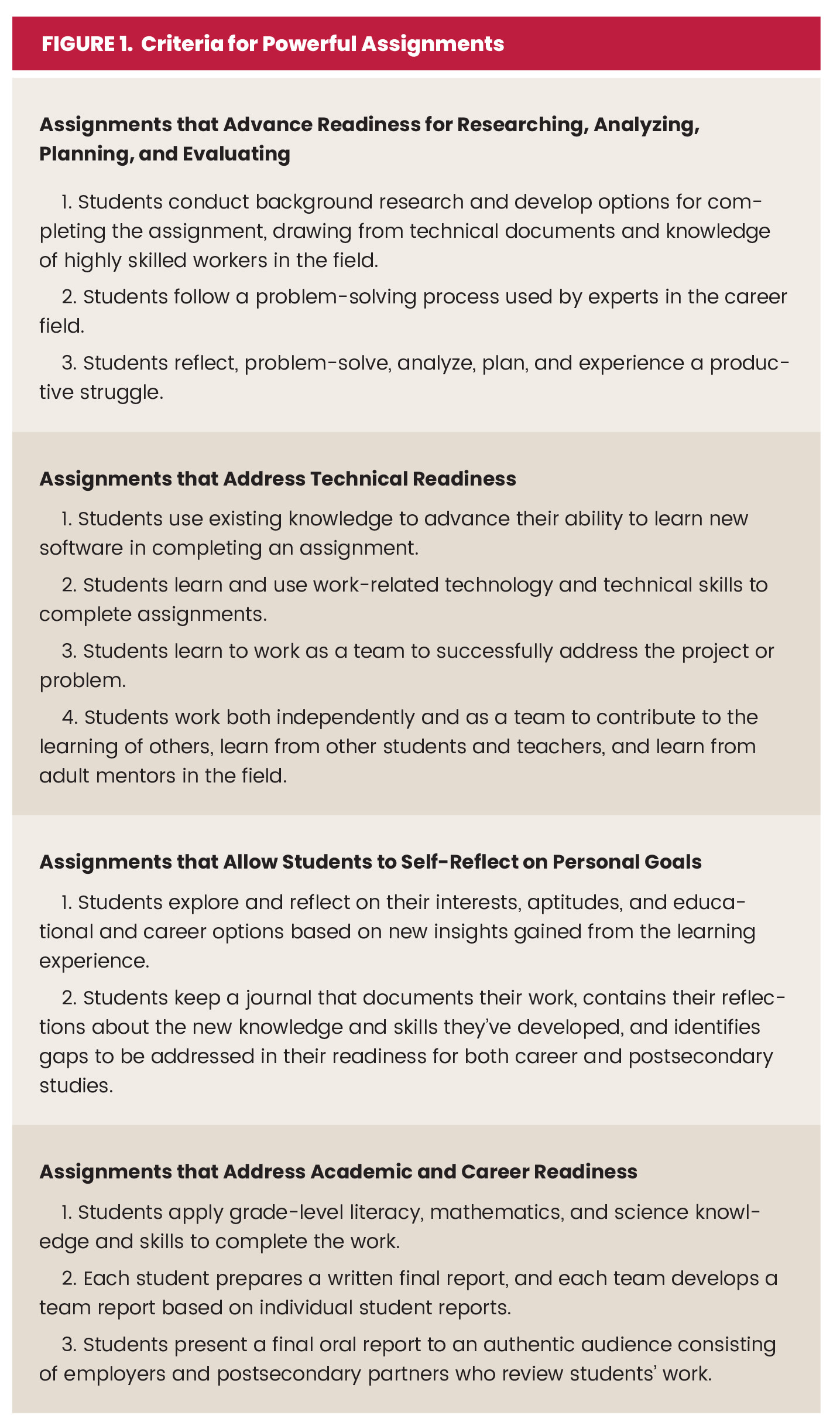

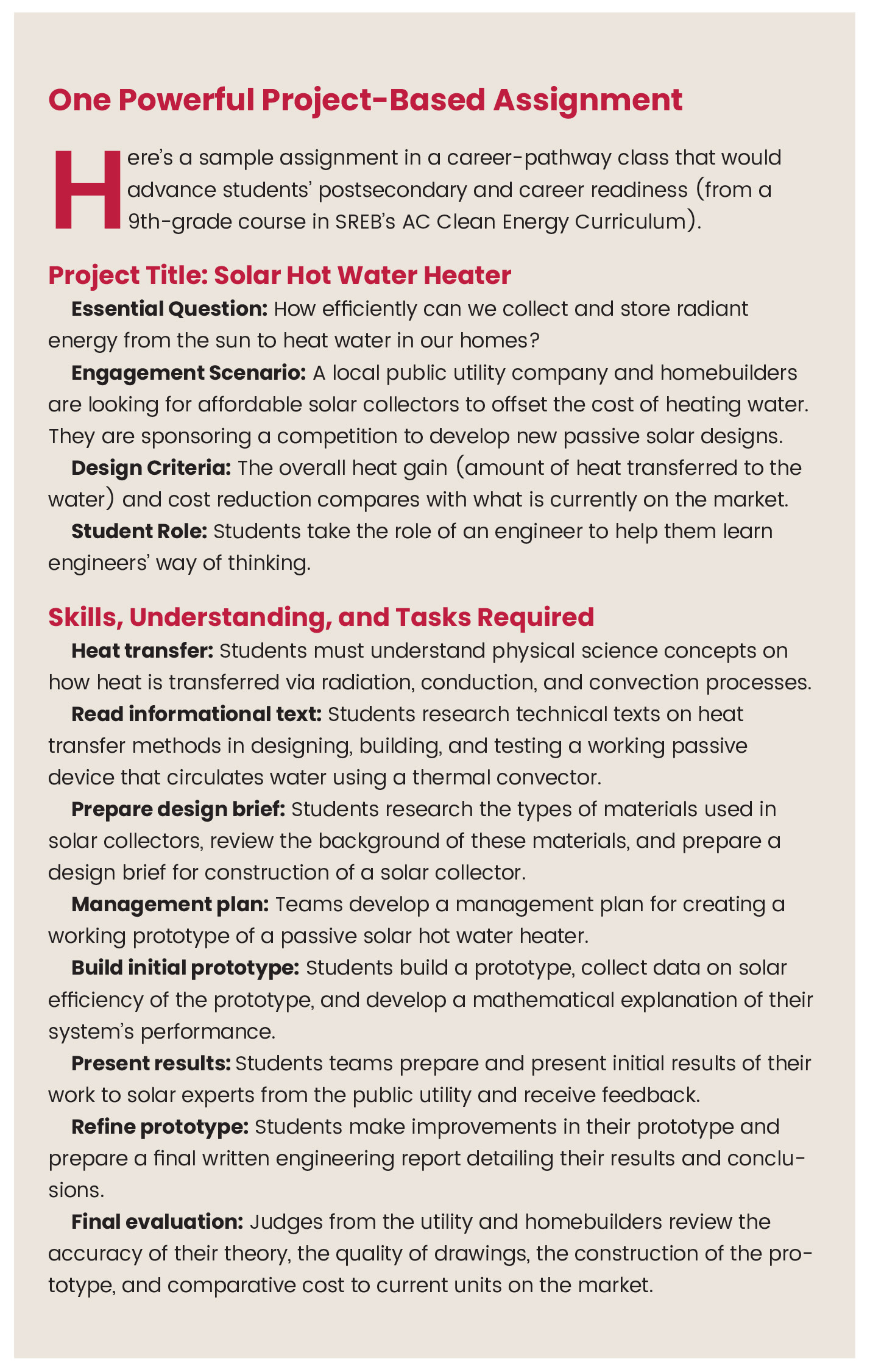

In 2010, SREB launched the Advanced Career initiative, working with partner states to create 36 courses in nine high-demand career fields. As a framework for these courses, more than 190 project-based assignments were developed, using the criteria outlined in Figure 1. (See "One Powerful Project-Based Assignment" for an example.) These criteria—which reflect views of leaders in post-secondary education and business on the knowledge and skills necessary for post-high school success—can guide any educator to power up existing assignments or develop new ones.

Teachers who lead Advanced Career classes have seen how assignments meeting these criteria change students' experiences. One high school teacher said:

The excitement, depth of engagement, and level of effort I see students making in the (AC) Clean Energy Technology classes is something I never saw in my 10 years of teaching chemistry. When students come to class early and stay late, and you see the level of engagement they have in their work, you're doing something right.

The vision driving the Advanced Career initiative also includes tearing down the silos erected when students are tracked into less-rigorous levels of academic courses. Tracking results in capable students receiving a steady diet of low-level assignments that fail to engage them in deeper learning experiences.

Combining academic courses with career studies can not only move high schools beyond tracking, but also increase the challenge and relevance of high school curricula across the board. When students can apply what they've learned in academic courses within a career context, it motivates these learners and increases retention of academic concepts (National Research Council, 1999). This especially boosts the learning of those students who are oriented to a career or career-training study right after high school. SREB's 30 years of research into achievement has found that the most powerful factor for increasing the percentage of career-oriented students who met college- and career-readiness standards is enrollment in "true" college preparatory courses (Bottoms, Preston, & Han, 2006). I say true because in creating course sequences intended to offer learning that opens college possibilities to more students, it's crucial (and tricky) to identify which sequence of courses in areas like math or science is rigorous enough in terms of work and thinking required to prep students for postsecondary success.

A true college preparatory science sequence, for instance, includes four lab-based science classes in which students do authentic science projects; if the course description doesn't include lab-based work, it isn't sufficient. Similarly, there are specific criteria to look for as to the rigor of ELA courses.

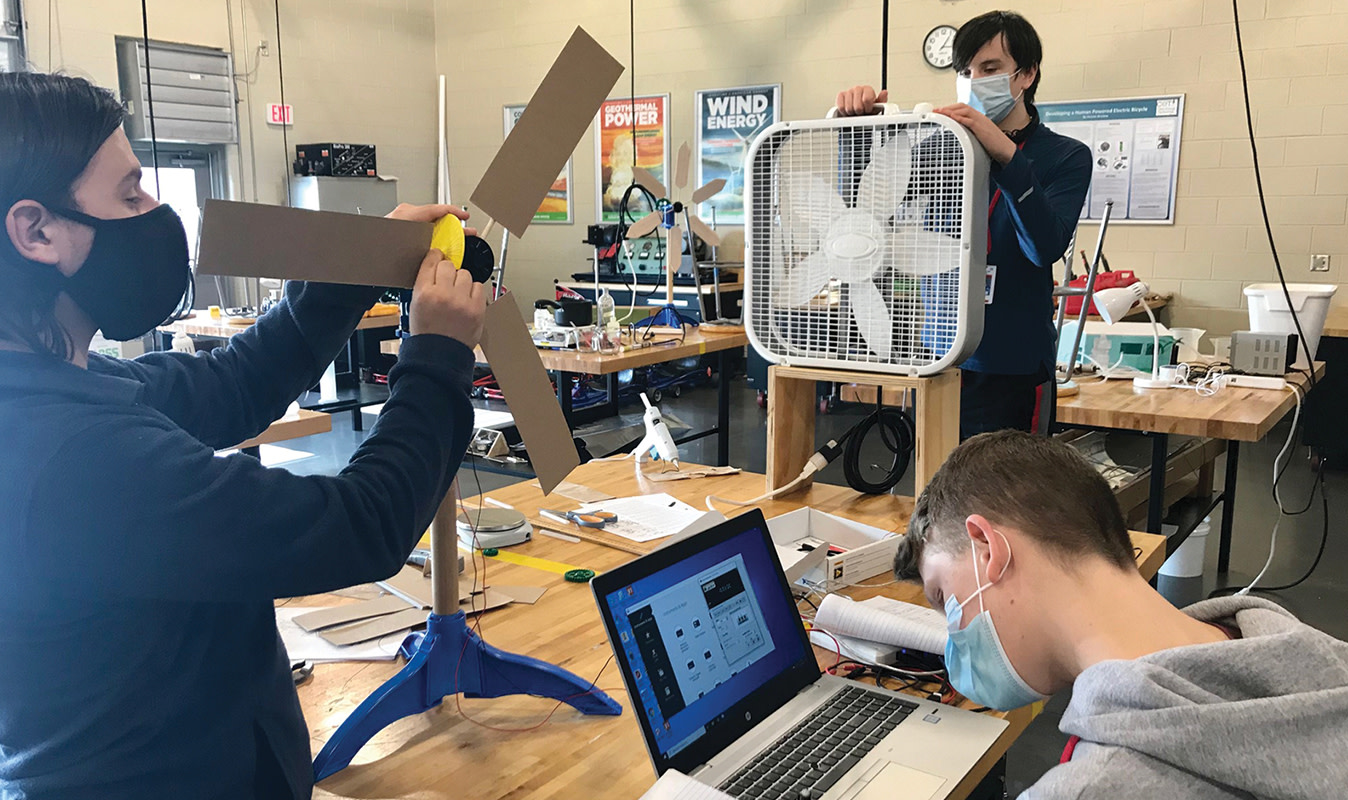

A clean energy technology student team works with a wind energy project at the Center for Advanced Technical Studies. (Photo courtesy of Patrick Smallwood.)

Coordination Between Academic and CTE Teachers

High schools adapting SREB's Advanced Career curriculum help career-pathway and academic teachers work together to connect project assignments with academic courses (and answer the perennial student question, "How will I use this in the real world?"). Any school that offers academic and CTE courses can create similar coordination. This process involves pathway teachers giving academic teachers in relevant subject areas information about a project that students they share are doing. Pathway and academic teachers discuss the project to ensure they understand the work and skills involved. Together, they determine what academic standards will be used in the project and how they might make connections for learners between content and skills involved in each course. Academic teachers can also suggest ways pathway teachers can support struggling students during their classes, while pathway teachers can consider ways content-area teachers can make connections to the project to help students grasp concepts in academic classes.

As a teacher of an Advanced Career global logistics course in one school said:

"An Algebra I teacher asked me what kind of math problems I was giving in my class, because her students were saying they'd already learned these concepts in global logistics class. This started a working relationship between this teacher and me to connect Algebra I concepts to real-world problems."

A principal who wants to launch this kind of coordination should start small-scale with one or two teams, each composed of one or two CTE teachers and an English language arts, mathematics, and science teacher who buy into the vision for breaking down silos between academics and CTE. This team should also include the scheduling person from the high school. All team members should work together to figure out how to schedule a cohort of students all these teachers would share and find four hours each month for the team to co-plan and design connected learning assignments.

How One School Went All In

Let's examine how one school began centering its CTE instruction on rigorous project-based assignments. In 2014, Randy Gooch, director of the Columbia Career and Technology Center in Columbia, Missouri, launched a five-year effort to redesign CTE classes around project-based assignments that required students to apply a mix of academic, technical, technological, cognitive, digital, and social-emotional skills. (Columbia Career is one of a network of career and technology centers at which 11th and 12th grade students generally spend half of their school day).

Gooch and the center teachers agreed that for five years, their professional development would focus on designing and implementing project-based assignments that meet the SREB definition of a powerful assignment. Several teachers quickly grasped the concept of designing powerful assignments and became trainers who now work with new and veteran faculty on creating assignments.

"We had teachers who weren't enthusiastic about the effort," Gooch recalls. "However, they became motivated [and committed] as employer leaders began telling us that these projects reflected the type of work they want their employees to be able to do." Teachers also witnessed greater student motivation, ownership of learning, and effort. In five years, the school went "wall-to-wall" with project-based assignments in all classes. Gooch and his colleagues learned several lessons:

Don't begin by asking teachers to design a new project-based assignment. Instead, ask them to redesign an existing assignment so it meets the criteria for powerful assignments.

Develop your own trainers over time to work with new teachers on designing project-based assignments.

Have school administrators attend professional development sessions with teachers so they understand the vision and can support teachers.

Engage business and postsecondary community leaders. They can support your efforts and help resistant teachers understand that deeper learning experiences are essential in preparing students for today's job world.

Frequently showcase teachers' results and work.

Today most seniors at the center agree their assignments are rigorous and relevant. The majority pursue postsecondary studies. Enrollment has continued to grow as parents across the economic spectrum recognize the program's value in preparing youth for both careers and postsecondary studies.

Needed: Respect for Career and Technical Education

SREB's vision of fully connecting CTE courses and academic studies isn't a pipe dream. Models are out there, waiting to be emulated by school and teacher leaders who are motivated to learn and to grow themselves. Part of their work will be increasing understanding and respect for career and technical education as a different approach to learning within the school community. Despite many calls for reform, career and technical education has largely remained neglected and in the margins in most U.S. secondary schools, with little linkage into the academic fabric of high schools. This marginalization is a disservice to students.

Rigorous assignments in career-pathway classes connected to a college-ready academic core—and opportunities for postsecondary studies and rewarding employment—can prepare students for the real world of today and tomorrow.

Author's Note: Learn more about how SREB can help schools coordinate CTE and academics at sreb.org/SchoolImprovement. Any district seeking to develop career pathways involving rigorous academic work and CTE skills can have a free consultation on how to get started by contacting tim.shaughnessy@sreb.org. Reflect and Discuss

➛ Are there ways at your school or district for teachers of academic courses and teachers of CTE in related fields to coordinate in terms of what and how students are taught?

➛ Do you agree that, for many students, the typical high school curriculum has not adapted to current career-preparation demands? If so, what do you see as the barriers to change?

➛ Consider the criteria for powerful assignments in Figure 1 in terms of one of your student projects. How could you have students follow a problem-solving process, learn new software, or other criteria as part of the project?

Tomorrow's High School

Gene Bottom's book Tomorrow's High School outlines how schools can better prepare students for the world after high school.