Since collective teacher efficacy holds such incredible potential for improving student outcomes, it is essential for school leaders to think deeply about what it is, why it's important, and how it's developed. They must, in effect, recognize and embrace its complexity. When leaders explicitly tap into the sources of collective efficacy, they strengthen the team's belief that together they have the capability to positively affect change for their students. Leaders do this by (1) ensuring teams achieve success on tasks they may have thought were beyond their capability; (2) sharing successes experienced by those who were faced with similar challenges and opportunities; (3) conveying high expectations coupled with positive reassurance; and (4) maintaining an atmosphere of positivity and optimism. Both formal and informal leaders can create the conditions for teams to embrace a growth mindset and recognize collective impact, thus enhancing efficacy.

The concept of collective efficacy may seem simple—help teams make the link between their joint efforts and positive results—but it's actually quite complex. Hidden biases, faulty assumptions, and sometimes low expectations about what certain students can accomplish often surface as a result of this work. Leaders may find themselves in the position of having to skillfully navigate teams in co(n)fronting these limiting beliefs and helping teams reconcile the cognitive dissonance that is created as a result.

We use the term co(n)frontation (pronounced co-frontation) to describe that moment of opportunity in which a problem presents itself and the team exercises the professional discipline needed to deal with it appropriately. Professional co(n)frontations are characterized by analytic examinations of beliefs and practices based on evidence of impact as opposed to emotionally driven assumptions. During professional co(n)frontations, team members do not default to the lowest common denominator of agreement. Rather, they are willing to, in a respectful way, say "no" to ideas or failed practices in pursuit of what works best for learners now.

Co(n)frontational teams are reluctant to simply agree—with the principal, with past practice, with routine, with anything dissonant from what evidence and experience suggest is best. They consist of individuals who respectfully challenge the status quo and engage other team members in uncovering biases and assumptions. Such educator teams and leaders co(n)front what they think they know, what they are actually doing, and what they should do next. Confronting long-held assumptions is difficult enough when done privately; when done publicly, it requires mindful organization of team interactions.

Mindfully Organized Teams

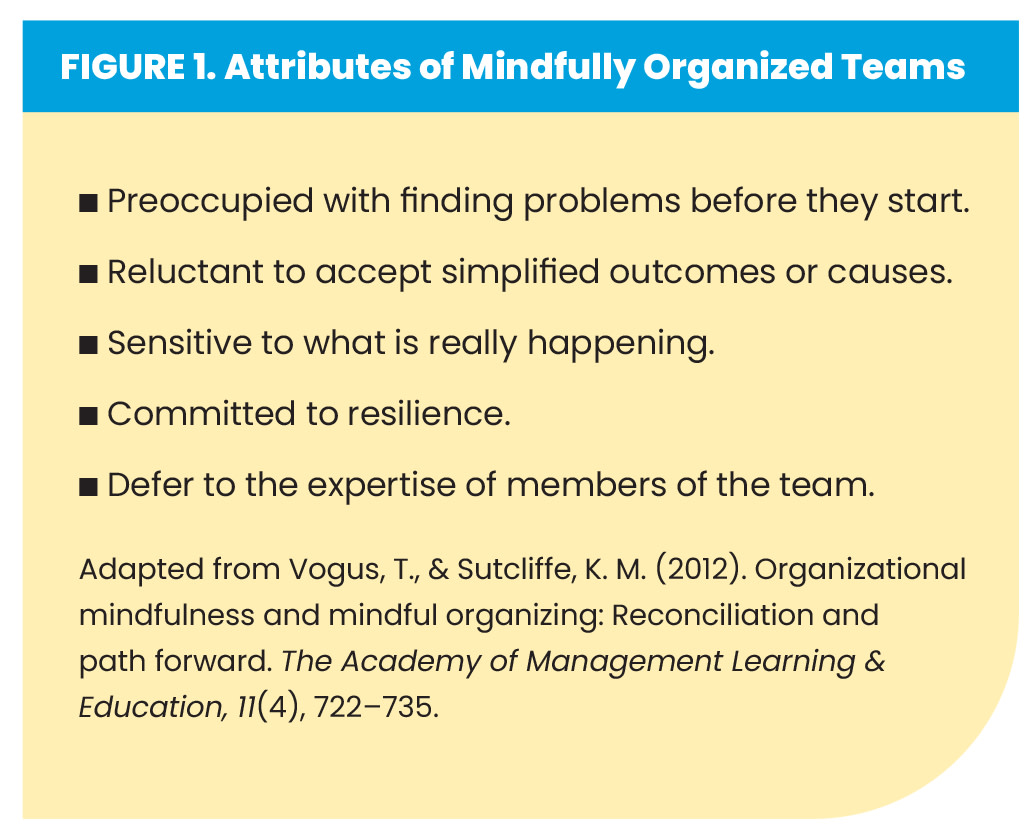

Organizational psychologists suggest that when a team is mindfully organized, its interactions reflect the five attributes shown in Figure 1. Mindfully organized teams do not accept things that aren't working; rather, they co(n)front what is not working and seek alternative solutions. In addition, they are reluctant to accept oversimplified outcomes or causes when reflecting on previous experiences and next steps. Mindfully organized teams are sensitive to what is actually happening rather than what is assumed to be happening. They are also committed to resilience by learning from failure. Finally, mindfully organized teams are composed of leaders and teachers who defer to the expertise of others (and each other) to better understand the unique needs of the school community and nuanced solutions.

Here, we share an illustration of a team from a high school in Ontario, Canada, that was presented with a problem and exercised the professional discipline and mindful organization needed to co(n)front it successfully. Trevor and Sandy, teachers in the technological and experiential learning department, were concerned that work placements for their students enrolled in apprenticeship programs were being postponed. They knew that postponing placements could have negative consequences on the lives of some students by causing them to fall behind, and even worse, drop out and not graduate from high school. Encouraged and joined by James, the assistant principal, Trevor and Sandy teamed up to inquire into the situation. When they uncovered the cause for the delays in students' work placements, they knew they had to co(n)front the faculty.

Teachers typically work to maintain a culture of nice, and in doing so, avoid critical conversations about ineffective instruction and assessment practices.

The reason why many students' work placements were being postponed was that they had not obtained the required mathematics and English credits during their first semester of 11th grade, with their failing grades most often being caused by late or missing work. The math and English teachers were deducting marks every day for work that was turned in late and assigning a zero when assignments were not submitted. The team knew that surfacing toxic grading practices among their colleagues would be challenging and risky, but since they had personally recruited students to the apprenticeship programs, they felt an even greater sense of obligation and responsibility to ensure that every student could participate.

With input and support from James, Trevor and Sandy proposed a plan that included the provision of additional time and support for students to complete assignments, closer monitoring of students' work completion, and better communication protocols to be used regularly between departments regarding students' progress and achievement. Over time, the team recruited faculty from different disciplines to help draft an up-to-date assessment policy and worked actively to support implementation of the policy. When team members met with resistance from some of their colleagues who were reluctant to change their grading practices, they engaged in respectful debate while maintaining professionalism.

Although Trevor and Sandy admitted that at times co(n)frontations proved to be challenging, they stayed committed to the plan, and it paid off. By the end of the first semester, all 27 students who were enrolled in apprenticeship programs successfully obtained their math and English credits and entered their work placements on time. The team confessed that when they started out, they didn't think their plan would be successful. But in seeing the positive results, they became more confident and motivated to continue their efforts—and some initially hesitant teachers came on board, as well.

Creating the Conditions for Co(n)frontation

Unlike the team described above, teachers typically work to maintain a culture of nice and in doing so, avoid critical conversations about ineffective instruction and assessment practices. We routinely hear educators convey expressions of collegial empathy—which can become problematic when it dissuades teams from critical examinations of their beliefs and current practices. Professional co(n)frontation is sabotaged as a result.

While the act of co(n)fronting and the state of being co(n)fronted might seem risky, it is a necessary precondition for building collective efficacy. When formal leaders, like James, communicate that it is OK for teams to question traditions, purpose, and current practice, they create an authentic space for teachers to lead the work of school improvement. Research demonstrates that there is a clear and strong relationship between the degree of teacher leadership and collective efficacy in schools (Derrington & Angelle, 2013). Therefore, it is important for leaders to empower staff to collectively co(n)front what has not, is not, or will not work regardless of where the work started.

Leaders can develop expectations for co(n)frontation and in the process enhance CTE by mindfully organizing team interactions in five ways.

1. Co(n)fronting the Blame Game

Failure should be seen as the beginning of new learning, not a blame-ladened ending. Ensuring that teams feel a sense of psychological safety is important. In her book The Fearless Organization (2018), Edmondson offers encouraging findings from teams who believed they were psychologically safe and explains how that belief contributed to owning their mistakes; to their learning, innovation, and collaboration; and to their greater likelihood of success. Small and large leadership gestures alike go a long way in supporting this work. Leaders could benefit from considering assembly over inquisition. Rather than rooting out the failure, which communicates a value for blame, leaders could assemble teams to thoroughly understand the problem, seek those who have the expertise necessary to solve it, and actualize co-constructed solutions. Doing so communicates a value for learning for which failure was merely the catalyst, not a catastrophist. The assistant principal in our example, James, embraced the opportunity to assemble a team that could learn from the problem, determine solutions, and meet with success. When teams experience success, it becomes a positive source of collective efficacy.

2. Co(n)fronting Simplifications

This aspect of mindfully organized teams deals with building the team's reluctance to simplify. Hargreaves and Fullan (2012) noted the irony that "disagreement is more frequent in schools with collaborative cultures because purposes, values, and their relationships are always up for discussion" (p. 113). Disagreements can only occur productively, however, in places where teams believe their relationships are not threatened as a consequence of professional debate.

To manage the disagreement and risk, which Hargreaves and Fullan noted "are sources of dynamic group learning and improvement" (p. 111), leaders must strengthen the team's skills for conflict resolution and negotiation. James led the work of shifting ineffective grading practices because he knew that it was important to help the faculty develop agreements about how to disagree constructively. He encouraged mutual respect among the faculty by showing genuine curiosity when differing perspectives arose, modeling norms of collaboration such as questioning and paraphrasing, and suspending judgement. Together, the faculty agreed on the following norms for disagreement: presume positive intentions, listen first and respond second, and support opinions with evidence of student learning. To discourage simple (easy) answers, the faculty also agreed to the mantra "questioning is caring."

3. Co(n)fronting Assumptions

This aspect of mindfully organized teams focuses on building the team's sensitivity to what is happening in the here and now. Weick and Sutcliffe (2015) described sensitivity as "a mix of awareness, alertness, and action that unfolds in real time and that is anchored in the present" (p. 79). Part of building sensitivity is to create "interruptions" that cause the team to "rethink, reorganize, redirect, and adapt what they are doing" (p. 89). Katz and Dack (2013) introduced the idea of intentionally interrupting "the status quo of professional learning in order to enable new learning that takes the form of permanent changes in thinking and practice" (p. 9).

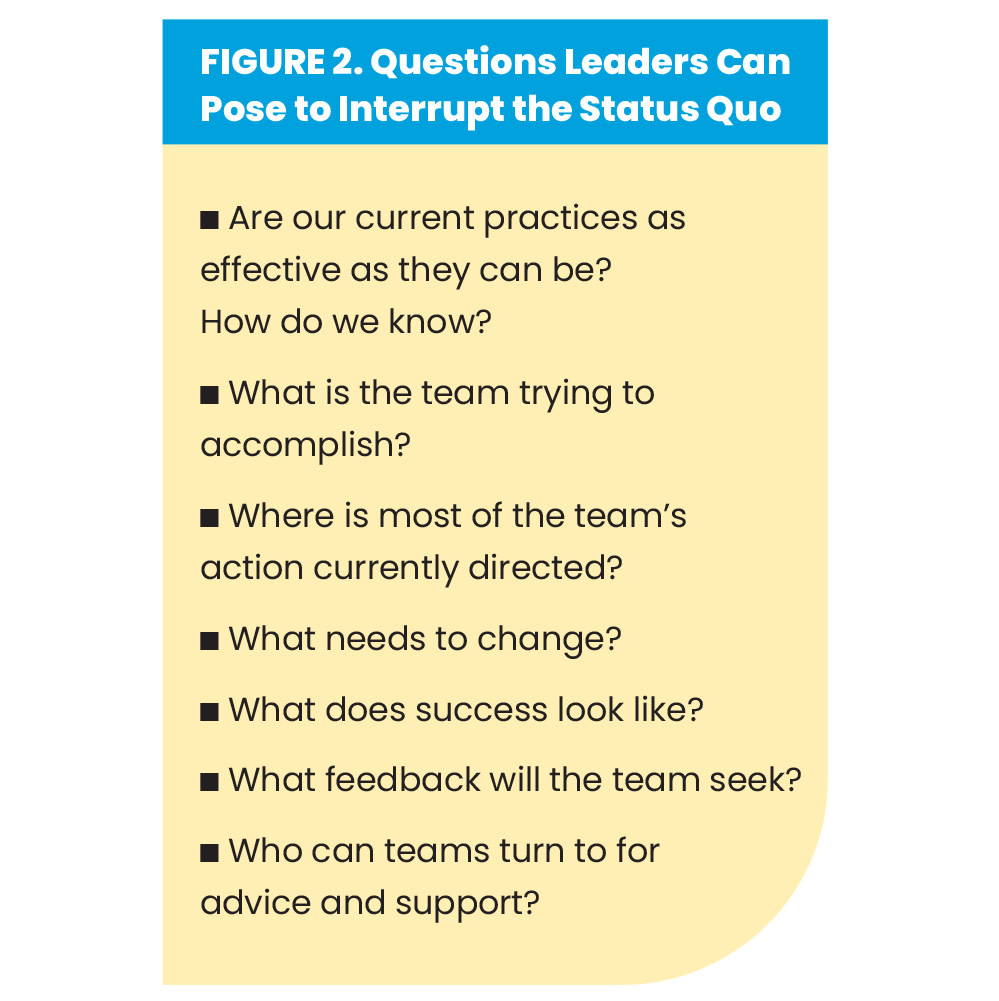

One strategy for causing such an interruption is to ask reflective questions (see Figure 2). Another strategy leaders can use to create interruptions that help teams focus on the here and now is to describe their interpretation of what they are thinking, experiencing, or observing moment to moment. When collaborating with teams, leaders might share what they observe in an objective way and make successful outcomes explicit. James did this by sharing data that demonstrated that more students were turning in assignments on time because of the efforts of the faculty, and as a result, there was an increase in credits gained. Efficacy is strengthened when team members observe each other's success and link success to joint efforts.

4. Co(n)fronting the Stigma of Failure

Ironically, mistakes in the aviation industry and the medical field, among other fields, contribute to the remarkably low number of actual catastrophic accidents. Organizational psychologist James Reason (1997) suggested that part of the human condition is to make mistakes, stating, "fallibility, like gravity, weather, and terrain, is just another foreseeable hazard in aviation" (p. 25). He advised that the only true failure is not learning from our mistakes.

Cultivating a sense of resilience requires that teams take stock of exactly what is occurring, and when challenges are found, face them knowing they offer an opportunity to improve. When leaders challenge the stigma of failure, they allow teams to generate excitement in the opportunities that failure creates. That opportunity starts when leaders construct new meaning from mistakes.

James modeled more resilient thinking by leading through collaborative inquiry. Asking the team why the postponements were happening was a simple way of recasting a potential failure as a chance to find a better way of doing business. After the team dug deeper to better understand the problem, James simply asked, "Is there a way to accommodate placements that also supports better learning outcomes for students?" This allowed the team to use the problem as a value-added experience rather than a failure that would potentially diminish their sense of efficacy. Once teams begin to independently redefine problems as opportunities, leaders can move from being persuaders to celebrators. They can generate enthusiasm by highlighting team interactions indicative of resilient thinking and the outcomes such thinking achieved.

How to Handle Failure

Failure should be seen as the beginning of new learning, not a blame-ladened ending. Ensuring that teams feel a sense of psychological safety is important.

5. Co(n)fronting Our Own Limits

Mindful organizing places an emphasis on intentionally deferring to the expertise of those who are closest to the origin of the problem. Teams are successfully co(n)frontational when individual members embrace the possibility that they may not have the necessary skills to meet the latest challenge on their own—or even as a collective. Co(n)fronting the limits of their combined skillsets opens the team up to the idea of building new capabilities while expanding their capacity for change.

In turn, this engages the team's mastery and vicarious experiences in a positive cycle of activation and reflection. The small act of asking team members their thoughts about how to face an emergent challenge, then using their feedback as part of the set of solutions to address that challenge, provides a type of social persuasion that builds a team's belief that they can affect improvement. More overtly, leaders should use every operational lever possible to create teacher leadership opportunities, be it chairing a committee, organizing an event, or co-leading collective inquiry into what works best for an emergent need. Doing so builds expertise and the capacity to lead well beyond just the leader themselves.

Mindfully Organizing Collective Efficacy

To enhance collective teacher efficacy, leaders must ensure that their staff knows how schools have successfully organized co(n)frontation. More important, the staff needs to understand how the pathways for disagreement work to support learner success. Leaders who mindfully organize team actions, alongside the team itself, empower teachers through processes and protocols to co(n)front misaligned proposals, ineffective initiatives, and ill-formed solutions. This ensures a greater likelihood of successful outcomes and collective efficacy.

Reflect & Discuss

➛ Look at the list of attributes of a mindfully organized team. Which of these are strengths of a team you're currently on? Which are weaknesses?

➛ What norms could you establish to ensure that your team disagrees more constructively?