The COVID-19 pandemic took a disproportionate toll on minority communities. These Americans lost jobs and wages, got sicker, and died—all at higher rates than white Americans (Hill & Artiga, 2022; Monte & Perez-Lopez, 2021). The impact on Black and Brown students' learning, well-being, and physical health also exceeded what, on average, their white peers experienced. The pandemic has been difficult for all families, but it has been materially different for people of color who are from communities with fewer resources. As the leader of the largest parent advocacy organization in the nation's capital, Parents Amplifying Voices in Education (PAVE), I have seen this inequity and tragedy unfold firsthand across our network of thousands of parents of color.

While these disparities have attracted headlines and much-needed government aid to schools, another powerful pandemic side effect for students of color and their families—this one potentially more positive—has received less attention: When learning went remote, parents whose voices had been historically ignored or neglected by schools suddenly found themselves with a window directly into their children's education.

In this sense, the pandemic offered us a critical lesson on the power of involving families directly in their children's learning. To truly recover from its disproportionate impact on minority students and their families, we will need to ensure schools are welcoming spaces for all families and develop new engagement strategies that accommodate working and low-income communities to ensure parents of color remain heard, engaged, and involved.

A Legacy of Exclusion

Of course, the pandemic hasn't ended yet, but almost all students are now learning either fully in-person or through hybrid means (U.S. Department of Education, 2021–2022). A closer look at the data on in-person vs. remote learning, however, reveals some disparate trends. At the end of the 2020–21 school year, while just 14 percent of white students were still learning remotely, 35 percent of Black students, 28 percent of Hispanic students, and more than half of Asian students were learning from home. During that same school year, nearly 60 percent of Black and Hispanic families and 66 percent of Asian families said they preferred remote learning, compared to only 34 percent of white families (Zamarro & Camp, 2021).

There are many reasons why the parents of non-white students may have opted to keep their children home, including a rational skepticism of the ability of schools to ensure the safety and well-being of these students. These misgivings are often the product of very real historical injustices committed by public institutions against Black and Brown communities, from Tulsa to Tuskegee to Flint.

Minority and immigrant parents have also faced barriers that make it more difficult to play an active role in their children's learning at school, including resource and time constraints, concerns about bias and feeling judged, and differences in cultural understandings and language with teachers and schools (Cherng, 2016). Likewise, schools often communicate with non-white parents differently (Anderson, 2016). Black parents, in particular, report feeling as though schools are indifferent to their concerns and even their presence (Latunde, 2017).

The truth is that many parents of color have not always felt welcome at their children's schools.

We must maintain and further integrate the communication pathways created as a side effect of remote learning into the in-person school experience.

Pandemic Shifts

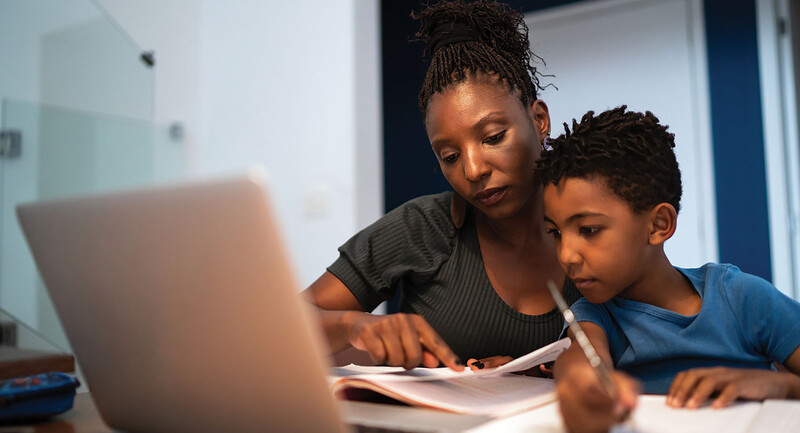

By sheer necessity, those systemic barriers began to change during the pandemic. Schools faced a long list of logistical challenges, chief among them a lack of adequate or reliable high-speed internet access, that made student engagement during remote learning a challenge, even when students were able to get online through free or low-cost internet providers. But when students could connect, many of their parents became more deeply engaged in what they were learning. Schools had to communicate with families about what was going on in the classroom because the classroom and the home were one and the same. As a result, many minority parents saw curriculum delivered first-hand and were more aware of the impact of school- and district-level decisions—something typically reserved for families who had the tools and money to navigate school bureaucracies.

Then, just as suddenly as this new relationship to schools began, it all came to an end for many parents. In some ways, schools are now more closed off than ever. The same challenges parents from underrepresented backgrounds faced before the pandemic have returned, but they are now compounded by strict precautions that often prevent them from even entering the building. Parents with disabilities, who may be especially vulnerable to COVID-19, have found themselves in a position where staying involved with their children's education means risking their health and safety.

Lessons for a New School Year

Schools and districts must determine how to leverage the robust channels of communication that emerged under remote learning now that they have transitioned back to in-person settings. At PAVE, we offer both in-person and virtual check-ins with parents at multiple times of the day and week—from virtual midday coffee chats on policy issues, to evening in-person meetings to build collective plans, to weekend community events. Schools can offer parents their own range of meeting options, including a virtual back-to-school nights at the start of the year and in-person home visits to build relationships with families.

Schools and districts must also intentionally cultivate a culture that ensures parents of color are as much a part of the conversation as those who have the most resources and feel most comfortable interacting with teachers and leaders. School systems can no longer hold parents and students with diverse backgrounds, incomes, races, cultures, and languages at an arm's distance when making decisions.

At PAVE, we asks parents to submit exit tickets at the end of every meeting or event we host. We then analyze our attendance and satisfaction data to identify which parents' voices are missing and inform decisions about our programs. As a follow-up, we conduct targeted text and call outreach from trusted staff and other parent leaders to make sure every parent feels included and does not encounter any barriers to their participation. We take the strategies schools use for student attendance and engagement and apply them to our families, and we have found that parent involvement flourishes as a result. School leaders might consider making similar reforms.

Parents of color deserve the right to accessible, timely, and consistent communication, as well as the right to transparency on funding, school staffing, and leadership. Opportunities for communication must be equitable and designed to meet parents where they are—in plain, accessible language and translated into other languages as necessary. Schools should offer a variety of methods and times for parents to share their perspectives and they should strive to ensure that families feel valued as partners in their children's education. And like all good partnerships, forging better relationships will be mutually beneficial.

As schools and parents navigate the complex and uncertain path to a "new normal," the goal should not be to simply restore in-person education to what it once was—an unequal and unfair system that empowered only a select few to have any real say in their children's education. We must maintain and further integrate the communication pathways created as a side effect of remote learning into the in-person school experience. For too long, parents of color and caregivers from underrepresented backgrounds have been shut out of conversations and decisions directly impacting their own children. The pandemic, in fits and starts, provided a small opening for that to change. Schools and districts must now do everything in their power to ensure a return to normalcy does not mean these important voices are ignored once again.