When Tommy Welch became principal at Meadowcreek High School in Norcross, Georgia, in 2011, he assembled a priority list of things to do. One was to introduce an instructional framework he knew of that would give Meadowcreek teachers a shared understanding of what good teaching looked like and a common language to discuss it. Welch figured this would be a quick item to check off his list. After all, through his previous work as an assistant principal and the training he had completed to be a principal, he was already familiar with the framework and considered it best practice.

Fortunately, Welch, like all first-year principals in Gwinnett County Public Schools, had a mentor to coach him as he settled into his new role. A retired principal, this mentor had some words of advice for Welch about his framework plan: Slow down. She asked Welch what teachers thought of the framework. The question stopped him in his tracks. As an assistant principal, he had always been the guy who got things done. But as principal, his mentor reminded him, Welch's job was to tap the capabilities of others. Involving teachers in the development of Meadowcreek's instructional framework would build buy-in for it, she suggested. The work might take longer, but this approach would foster collaboration among the faculty and a shared ownership of the school's mission.

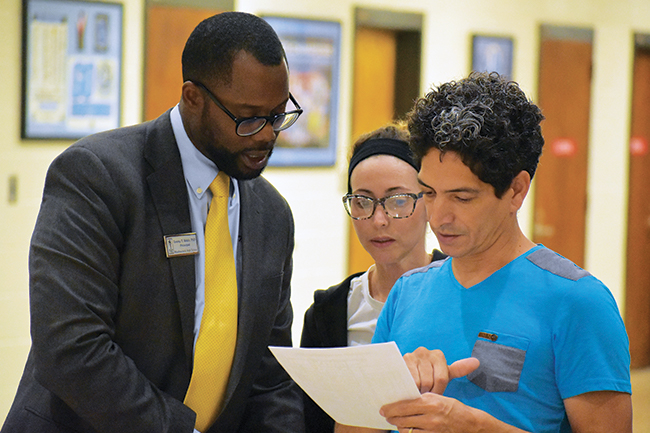

Tommy Welch, the principal of Meadowcreek High School in Norcross, Georgia, says he benefited from having a retired principal as a mentor when he started in his job. Now in his seventh year as principal, Welch has significantly boosted achievement at Meadowcreek.

Photos courtesy of Jimme Mckinley

Thanks to that gentle nudge, Welch convened his instructional leadership team, which was made up of teachers and other staff members, to seek their help in creating an instructional framework that would be customized for the school. The team reviewed student test scores, assessed instructional practices at Meadowcreek, and visited other schools to see different teaching styles in action. Their efforts exceeded Welch's expectations. The group not only developed a research-based framework for teaching at Meadowcreek, but also brought it to life. Team members organized professional development to explain the teaching model to the faculty. They observed in classrooms and provided constructive feedback to teachers. They also advised Welch to hire and train teachers according to the framework, and then hold the entire faculty accountable for following it.

"It was an "a-ha!" moment for me," recalls Welch. "The typical first-year principal wants to show everyone what he knows, but the most effective way to lead is to empower others. I learned the value of that from my mentor."

Building Support

Welch's experience of working with a mentor is not as uncommon as it might have been a few years ago. The days when new principals get the keys to the building and then are left to fend for themselves are gradually disappearing, with a growing number of districts acting on the idea that on-the-ground support is vital to a school leader's success. That support—in the form of mentoring, guidance from a supervisor, and targeted professional development—goes way beyond tips on whom to call when the boiler breaks down. At its best, it centers on the greatest challenge facing principals today: how to create a learning environment where all students thrive.

Research shows that an effective principal is the second most important school-level factor associated with student achievement, right after effective teachers (Leithwood et al., 2004). Recognizing this, many states have revamped or are reconsidering their professional standards for principals to put a stronger emphasis on how well school leaders improve the quality of teaching, use data to inform instruction, and exhibit other forms of instructional leadership (Riley & Meredith, 2017).

Now they're poised to take the next step: providing meaningful assistance to principals as they engage in this important but difficult work. Improving on-the-job support for principals is the top priority among two dozen states involved in an initiative to strengthen school leadership run by the Council of Chief State School Officers (Riley & Meredith, 2017). Many states are seeking federal funds to do so as part of their plans under the Every Student Succeeds Act (New Leaders, 2018).

This represents a significant shift in protocol. A 2015 RAND survey of principals nationwide found that only one-third receive all three types of on-the-job assistance: mentoring, professional development, and guidance from their supervisor (Johnston, Kaufman, & Thompson, 2016). Indeed, on-the-job support for school leaders has historically been a low priority for many districts. In the 2014–2015 school year, only 31 percent of districts reported spending any of their federal Title II dollars on principal development, compared to 66 percent allocating funds to teacher development (U.S. Department of Education, 2015).

Gwinnett County Public Schools was an early adopter of mentoring for school leaders, having launched its program in 2005. The district has since expanded its mentor corps to 11 retired principals who coach novice leaders for at least the first two years of those principals' appointment. Mentors undergo rigorous training on coaching strategies and carefully record every interaction with their mentees on an online system designed by the district.

The system captures how often the mentors discuss different topics, such as curriculum development and instructional planning. The district uses the data not only to get a better sense of their principals' needs and progress, but also to fine-tune preservice training for aspiring principals, says Glenn Pethel, Gwinnett's assistant superintendent for leadership development. By tracking the data gathered by its principal-mentors, for example, the district learned that novice principals often struggle to maximize the strengths of their team. That insight spurred the district to devote more time in pre-service training to developing the principal's capacity to empower staff to improve student performance.

Mentoring also informs the district's ongoing training for school leaders by identifying the skills and knowledge that sitting principals need to sharpen. Pethel measures the impact of the mentoring program by the positive feedback he hears from principals and the degree to which they move their schools forward. Welch, now in his seventh year as Meadowcreek's principal, is Exhibit A: During his tenure, the school's graduation rate has risen 28 percent and SAT scores are up 40 percent.

Adding Instructional Value

Gwinnett County was one of six districts that participated in The Wallace Foundation's Principal Pipeline Initiative, a multiyear effort that aimed to strengthen school leadership through targeted support for specific leadership policies and practices, including on-the-job support (Mendels, 2017). Research on the initiative shows that novice principals in the districts ranked mentoring as the support they valued the most, commonly using words like "lifesaver" and "cheerleader" to describe their mentors (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016).

Indeed, mentoring appeared to bolster the effect of other types of aid, with mentored principals more likely than others to give high marks to the professional development and supervisor support they had received. Other research, including Rand's national survey, suggests that principals value mentoring most when it focuses on instruction.

Even veteran educators benefit from mentoring once they're in charge of a school. Felicia Eybl spent a decade as a teacher and another decade as an assistant principal in the Charlotte-Mecklenburg school district in North Carolina—another Pipeline Initiative district—before becoming the principal at Waddell Language Academy, a K–8 language-immersion magnet school, in 2015. Like other new leaders in the system, Eybl received mentoring from a retired principal. Among other things, Eybl's mentor tagged along to meetings and observed her interactions with her administrative team. Her assessment? "I was doing all the heavy lifting," Eybl recalls. For example, Eybl was making it a point to visit classrooms and give feedback to teachers on their instructional practice. She wanted her two assistant principals and other members of her administrative team to do the same, but their walkthroughs weren't happening consistently—and Eybl, her mentor noticed, was letting her team off the hook. "She showed me that I really had to set high expectations and hold them accountable," said Eybl. "It was my job as instructional leader to do a lot, but I also had people on my team who could do a lot more."

With her mentor's guidance, Eybl created a new walkthrough schedule to help her team better keep track of their observation responsibilities. She also made a walkthrough observation form for staff to fill out. In meetings, she stressed the importance of the observations, noting that they would help identify appropriate professional learning for teachers. And she didn't let it slide when staff members claimed they couldn't squeeze them in. Today, Waddell teachers aren't surprised when Eybl or another administrator drops by their classroom. Eybl's two assistant principals, for example, each visit 10 to 12 classes a week. The walkthroughs deepened the team's understanding of instructional practices at the school. After teachers had been trained on language-immersion strategies, for instance, Eybl and her team were able to see how well they incorporated the techniques into their instruction.

"Fresh Set of Eyes"

One-on-one mentoring tends to be reserved for novice principals, those leading turnaround schools, and those in need of special intervention. But increasingly, states and districts are recognizing that all principals need better instructional support—and they're eyeing the people who supervise and evaluate principals to deliver it. Traditionally, principal supervisors have concentrated on overseeing administration, operations, and compliance, but the breakdown of the job is now being reconsidered. Three out of four states involved in CCSSO's initiative on school leadership plan to prioritize principal supervisor practices that better support developing principals. Only 6 percent said this had been a priority in the past (Riley & Meredith, 2017).

A separate Wallace Foundation initiative begun in 2014 aims to support districts' efforts to change the supervisor's role so it focuses more heavily on strengthening a principal's skills as an instructional leader. So far, the six districts involved are seeing positive results from the job redesign, according to Ellen Goldring, a Vanderbilt University professor who is leading a study on the initiative. "The clear benefits include supervisors spending time in schools and working with networks of principals on instructional leadership," she says. "Supervisors engage in walkthroughs, coaching, and providing more ongoing feedback to principals; they have a deep sense of the context of each principal's school and develop closer relationships" (Wallace Foundation, 2018). In a survey, more than 75 percent of principals involved in the program said that their supervisors "usually" or "almost always" offered them "actionable feedback" (Goldring et al., 2018).

Providing such support requires supervisors to devote significant time to working with principals, something the Pipeline Initiative districts discovered as well when they recast the principal supervisor role. Some Pipeline districts reconfigured jobs at the central office to allow them to hire more supervisors and reduce the number of principals each oversaw. Other districts initially used seed money from Wallace to add more supervisors (Turnbull et al., 2016). According to the foundation, some districts were also able to tap federal funds to assist in expanding their supervisor corps.

Principals themselves have generally welcomed having their bosses in the building more often, noting that they appreciated their guidance in areas such as creating or improving data-driven instruction. Over time, they began to regard the support they received from their supervisors almost as highly as the support they received from their mentor or coach (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016). Amber Cronin, a fourth-year principal in Hillsborough County Public Schools in Florida, appreciates her manager's "fresh set of eyes" during their joint classroom observations at her school, Pizzo Elementary. "She really pushes my thinking sometimes," Cronin says. "It's a model for what I can do with my teachers."

Hillsborough County provides its principals with another valuable support resource: each other. Supervisors in the district organize monthly small gatherings of school leaders to discuss curriculum and academic standards and share instructional strategies. The meetings take place during the school day so principals can observe classrooms and then, out in the hall, compare notes and practice the feedback they would give to teachers. "We're constantly encouraging students and teachers to better themselves," says Cronin. "It's great that we as principals have the opportunity to do the same."

Similarly, Eybl was able to lean on fellow school leaders during her transition at Waddell. In addition to her mentor, Eybl was assigned to a small peer network consisting of a veteran principal and four novice leaders. All were leading a language-immersion school or one with a high percentage of English language learners. No topic was off-limits during the group's quarterly meetings and frequent conference calls. They consoled each other after rough PTA meetings. They brainstormed how to get teachers to collaborate on instructional planning and reminded each other of deadlines for district reports. The network officially disbanded after two years, but the strong bond created endures. "I know I can call any of them and say, "This is happening. How should I approach it?"" says Eybl. "We were really there for each other and still are."

An Investment in Instructional Improvement

As a rule, principals favor individualized support over traditional workshop-style professional development. In the districts participating in Wallace's Pipeline Initiative, 40 percent of principals surveyed "strongly agreed" that mentors or supervisors had helped them in responding to pressing issues at their schools, almost double the figure for traditional professional development (Anderson & Turnbull, 2016).

Of course, providing better support for principals comes with a higher price tag. In the Pipeline districts, on-the-job support and evaluation was by far the most expensive part of the program, amounting to about $14,000 per district principal. Mentoring and professional development accounted for the bulk of those expenditures (Kaufman et al., 2017).

So is it worth the investment? Just ask Welch. Putting teachers in charge of Meadowcreek's instructional framework had a long-lasting impact. It marked the beginning of a new school culture, one rooted in collaboration and trust that he believes has led to better outcomes for Meadowcreek students. "If we empower teachers, then they will empower students through the curriculum," he says. "Without my mentor's guidance, it would have taken me years to get that."

Guiding Questions

› As a school leader, would you be interested in having a dedicated mentor or supervisor? Why or why not?

› Why do you think more districts are turning to principal mentoring and supervision today?

› How could your school or district do a better job of providing on-the-ground support for instructional leaders?