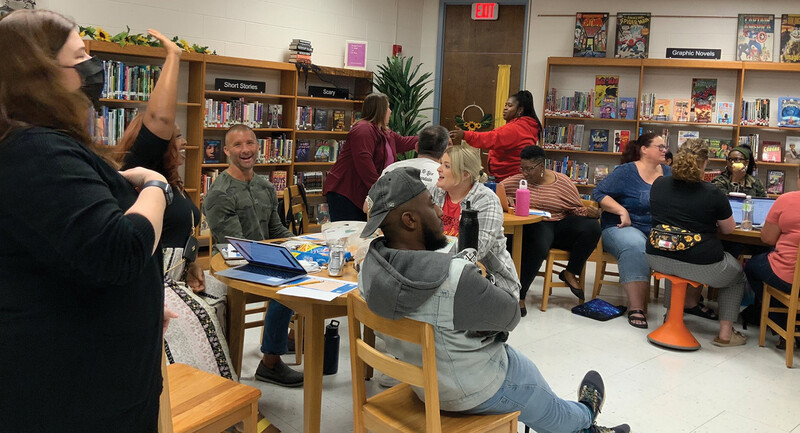

After a year of working remotely with the school's principal and leadership team, we had arrived at Butcher Greene Elementary, one of seven schools serving K–8 students in Grandview C-4 School District in Grandview, Missouri, a high-poverty district. Along with superintendent Kenny Rodrequez and assistant superintendent Joana King, we were attending a meeting of the school's leadership team. As we walked to the school on that cloudy day in April 2022, the sun peeked out from behind a cloud and the sky brightened. In retrospect, that breakthrough seems symbolic of what was about to happen inside the school.

As team members and Butcher Greene's Principal Kelly Nash streamed into the school's library, we both remember thinking, "These folks look tired." It was the end of the school day and six weeks from the end of a school year that had been marked by pandemic-related disruptions. Still, weariness wasn't the only emotion we sensed; something in the air felt like a combination of trepidation and excitement.

Early in the meeting, the focus became the unlikelihood of the school reaching its ambitious improvement goal of 65 percent of students reading at grade level by the year's end. One team member said, "We're probably not going to meet our goal." Most of the team concurred.

This was a critical juncture for this dedicated group of educators. Their response to not meeting their goal would indicate whether they had developed the leadership capacity and collective efficacy necessary to continue on the path to comprehensive school improvement. In the past, this discussion might have devolved into a blame game—but not this time. With an element of wonder in her voice, another team member mused, "We have to remember, we've made so much growth. What we're doing is working!" Another shared, "I'm not giving up yet; we have six more weeks!"

Team members began to remind each other of all they had learned and accomplished in spite of their early doubts and resistance—and the pandemic. The conversation turned to problem solving. The district's lead reading interventionist and the school's instructional coach contributed ideas for how they would support classroom teachers in the waning weeks of the school year. Team members who were classroom teachers knew exactly which of their students weren't reading at grade level and what they needed to do to support them. These teacher leaders would return to their professional learning communities to support their colleagues in staying the course.

After the meeting, assistant superintendent King noted, "They weren't feeling a sense of failure.… They were feeling like they weren't ready to give up, and they were energized."

None of the high performing, high-poverty schools we studied 'intervened' their way to better academic outcomes.

We've seen this kind of shift before when consulting with high-poverty schools. We've learned that when educators commit to transformative action, a contagious energy emerges that stems from knowing what they do matters—both for their students and for their collective effort toward a worthy goal.

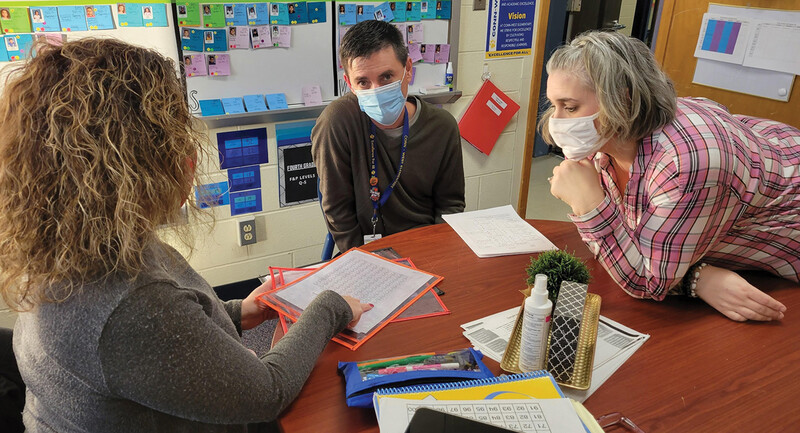

Credit: PHOTO COURTESY OF GRANDVIEW C-4 SCHOOL DISTRICTTeachers from Butcher Greene Elementary in Grandview C-4 school district collaborate to look at data, reflect and learn together, and plan high-quality instruction for all students.

Learning from Schools on the Path to Improvement

In 2006, Harvard's Richard Elmore asserted, "We have much more to learn from studying high-poverty schools that are on the path to improvement than we do from studying nominally high-performing schools that are producing a significant portion of their performance through social class rather than instruction" (p. 943). Each high-performing, high-poverty school we've studied over the last 15 years found the early phase of its improvement effort challenging. Each school's transformational journey was unique, yet all raised expectations of their educators and students and enhanced their leadership capacity to cultivate collective efficacy. And in each school, student achievement significantly improved, with the majority of students eventually meeting grade-level proficiency.

Grandview C-4 is not yet a district of high-performing, high-poverty schools, and much work remains. But a glimpse into the early phase of their improvement journey provides the opportunity for the learning Elmore noted. The district is better positioned for success than it was prior to the pandemic. Interrupted but not stalled, district leaders have continued to disrupt the adverse impact of poverty on learning. Modest, yet steady gains in student achievement, and prominent improvement in district systems and professional practice, indicate the leaders in this district have improved their ability to improve. We hope our insights from working with this district will provide encouragement to similar districts eager to improve.

We Can't Intervene Our Way to Academic Recovery

Scholars, policymakers, educators, and parents are concerned about the long-term implications of the pandemic on the learning of a generation of young people. Media outlets have covered this issue extensively, and academics and experts have made urgent calls for action to ensure "academic recovery." Widespread agreement exists that students living in poverty and students of color were most negatively impacted by pandemic-related disruptions to schooling. Suggested solutions for academic recovery primarily include accelerating tutoring and mentoring, extending the school day, offering summer school, and implementing practices to address students' social, emotional, and mental health needs.

These recommended measures are the same targeted interventions commonly deployed in struggling schools, including high-poverty, high-performing schools, to tackle underachievement. At first glance, these remedies might seem to be just the right cure. But if we think about it, academic recovery implies that when we "recover," we will be back to where we were—and academically "well."

But none of the high-poverty, high-performing schools we studied "intervened" their way to better academic outcomes. Commonly used interventions like tutoring aren't intended to improve the teaching and learning that happens in classrooms every day. Use of these interventions (and others) in high-poverty, low-performing schools is necessary but not sufficient for authentic academic recovery that elevates all students to grade-level proficiency. A plan of action for struggling high-poverty schools requires remedies that will eliminate long-standing inequities in students' opportunities to learn—and reverse historic trends of underachievement. Central among these remedies is building the capacity of leaders and educators to improve the quality of teaching in every classroom.

If high-quality instruction is happening in every classroom, there will be greater equality in students' opportunities, a higher chance that achievement will improve, and less need for interventions. That's what Butcher Greene Elementary and the other schools in Grandview C-4 are working toward. And it's where leaders in any high-poverty, low-performing school should begin—by raising expectations (for their students and for themselves) and increasing their capacity to cultivate collective efficacy.

Credit: PHOTO COURTESY OF GRANDVIEW C-4 SCHOOL DISTRICTTeachers from Conn-West Elementary in Grandview C-4 school district collaborate.

Building Districtwide Capacity to Improve

Although set among rolling hills, communities like Grandview (population 32,965) near Kansas City, Missouri, are becoming increasingly urbanized. They are also becoming increasingly diverse. 52 percent of the students in Grandview C-4 district are Black, 20 percent Latino, 20 percent white, and 8 percent identify as Asian, Indian, or two or more races. Seventy percent of the population qualifies for free or reduced-price meals in school. And like many high-poverty districts across the country, there is substantial underachievement.

When Kenny Rodrequez became superintendent of Grandview C-4 in 2016, his vision was to create a sustainable path toward academic improvement for all children in the district. He and assistant superintendent King led the district in aligning curriculum and instruction to state standards, building an inclusive communication approach to better connect the district with the community, and assembling a team of school leaders committed to confronting low student achievement.

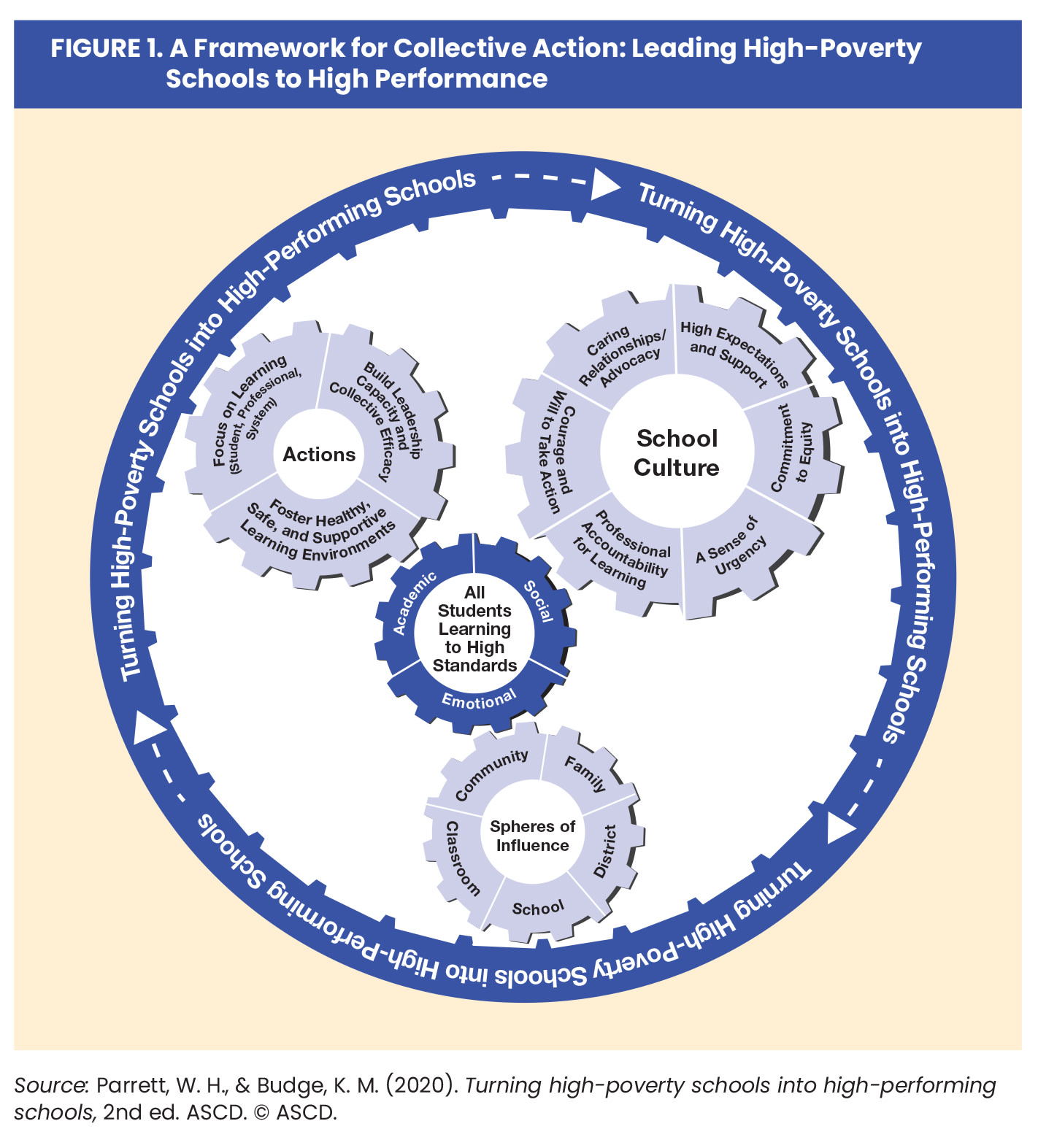

Superintendent Rodrequez was determined to create a culture of high expectations and caring relationships—one that realizes systemic equity, uses culturally responsive practices, and develops a districtwide understanding of the adverse effects of poverty on student learning. With the school board's support, he invited us to assist and support that commitment. Throughout this partnership, we used our Framework for Collective Action (see Figure 1) to guide and support educators from various vantage points in the school system. We've found committing to this framework inspires optimism about what's possible and prompts necessary action in schools.

That April 2022 meeting of Butcher Greene's leadership team illustrates the kind of breakthrough their team—and teams from other district schools—experienced during the last school year. While the school fell short of its two-year improvement goal (65 percent of students reading on grade level in year 1 and 85 percent by year 2), it raised expectations for its students and educators and cultivated sufficient collective efficacy to improve teaching and learning. In the 2021–22 school year, Butcher Greene increased the percentage of students reading on grade level by 38 percentage points—no small feat for any school. (And in the 2018–19 school year, Butcher Greene had increased the percentage of students reading on grade level by 26 points.)

Achievement data in five of the seven K–8 schools in the district reveals similar improvement. During the 2018–19 school year, student achievement in literacy increased by 29 percentage points across the district, and in 2021–22, by 39 percentage points. Let's look at what the district did to get such improvement.

Strengthening Leadership

Leadership coaching in the district played a critical role in raising expectations and building leadership capacity to cultivate collective efficacy. We provided intensive, customized, job-embedded coaching to the principals and leadership teams of three schools. We were able to build relational trust, allowing for difficult conversations, introspection, and reflection within a safe environment. Dr. King participated in the weekly coaching sessions with the school principals and teams, as well as her own weekly coaching cycles with us. Her "boots on the ground" leadership proved invaluable, providing both pressure and support to principals and leadership teams.

Stopping the Blame Game and Raising Expectations

There's little question that the gross inequity between the resources typically available in high-poverty schools and those in more affluent schools makes the work of school improvement much more difficult—and contributes to the "uncommonness" of high-performing, high-poverty schools. Nonetheless, we believe it is educators' beliefs—not the familiar challenge of inequitable resource allocation—that pose the greatest barrier to improving learning and achievement in high-poverty schools.

Educators in low-performing, high-poverty schools too often hold low expectations of students, themselves, and their colleagues. Educators' mental maps, regardless of where they work, are likely influenced by stereotypes about poverty and people who live in poverty, stereotypes deeply embedded in U.S. society. Although it's possible to change our mental maps, it's not easy. Humans tend to embrace information that confirms or conforms to what we already believe and reject contradictory information. This can result in educators blaming students and families for low achievement rather than assuming the responsibility of examining their own practice when students struggle.

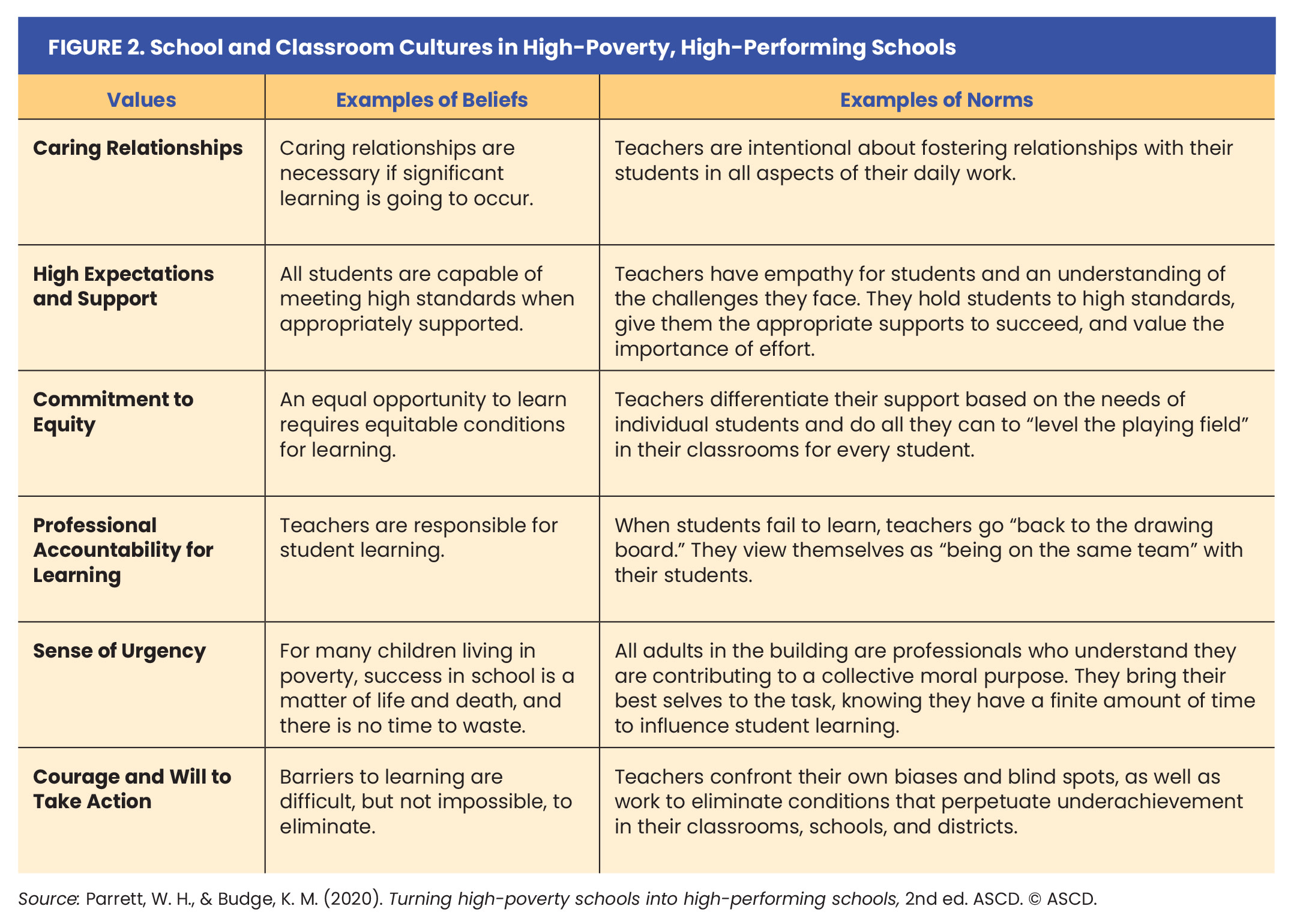

Educators' beliefs change most when they are supported in developing self- and collective-efficacy. It's the best way out of the blame game. With Grandview C-4, our initial step in challenging leaders' and teachers' beliefs about poverty, families living in poverty, the intersection of poverty with race, and the importance of high expectations was to provide a series of professional learning and planning workshops. In these sessions, leaders from throughout the district engaged in case-based learning and other activities designed to dispel common stereotypes and misunderstandings about poverty and people who live in poverty. Leaders were introduced to the School Culture aspect of the Framework for Collective Action (see Figure 2) to help them develop an understanding of the kind of culture required to "disrupt" the adverse influence of poverty on students' lives and learning. Participants compared and contrasted their school and classroom cultures with the values, beliefs, and norms in Figure 2.

Holding higher expectations for ourselves and our students takes courage; we must often push back on our own beliefs. For example, in providing leadership coaching to Marcy Simon, principal of Conn-West Elementary, and her leadership team, it became apparent that getting team consensus on the need to hold higher expectations and set an ambitious improvement goal posed a significant challenge. We built relational trust with and among the leadership team while we enhanced their knowledge base related to what is possible in a high-poverty, racially diverse school. Ultimately, Principal Simon and team members' willingness to be introspective and to have difficult conversations led to setting an ambitious goal and a plan for meeting that goal over two years.

Cultivating Collective Efficacy

Collective teacher efficacy exists when teachers believe they are collectively capable of implementing a course of action that will improve student outcomes (Donohoo, 2017), and they have data that confirms that belief (Hattie, 2018). While there is a strong negative correlation between socioeconomic status and student achievement, collective teacher efficacy appears to be three times more predictive, ranking as the No. 1 factor positively influencing achievement (Hattie, 2019). Jenni Donohoo (2017), a well-known voice on collective efficacy, contends that "amazing things happen when a school staff shares the belief that they are able to achieve collective goals and overcome challenges to impact student achievement."

Although it can be developed in other ways, collective efficacy is most powerfully cultivated through experiencing successes. Six conditions help teachers achieve collective efficacy :

Teachers take on leadership roles and have the power to make decisions of schoolwide importance.

There is consensus among staff about their goal, and they are involved in planning, implementing, and monitoring process toward that goal.

Teachers assume a learning stance and co-construct knowledge about effective teaching.

Cohesion exists concerning fundamental and organizational issues, such as what excellence in teaching looks like and what needs to be done to improve teaching in each classroom.

Leaders are responsive to teachers' needs and there is a spirit of reciprocity.

Systems of interventions effectively support all students to learn—and all staff to recognize their role and see their effort making a difference. (Donohoo, 2017)

Establishing conditions for collective efficacy to flourish requires leadership characterized by a spirit of reciprocity and by encouragement of shared and distributed leadership.

Modeling Reciprocal Accountability

Throughout the challenges posed by the pandemic, Rodrequez and King modelled a relationship of reciprocal accountability between themselves and the district's educators. They understood that the formal authority they had to hold principals and teachers accountable for some action or outcome required a complementary responsibility on their part to ensure principals and teachers had the capacity to do what was asked of them. Our partnership with them was nested within many other factors that fed Grandview C-4's capacity to improve, including the comprehensive services of a curriculum and instruction department. Superintendent Rodrequez provided district-wide professional learning on the topic of culturally responsive practice, a multi-year endeavor to which he remains committed.

Rodrequez and King hired a lead reading interventionist to support other reading interventionists throughout the district and coach teachers directly. She provided immersive workshops on literacy teaching strategies, followed by 1-1 coaching cycles, and targeted discussions in PLCs. This approach greatly contributed to teachers having mastery experiences that cultivated their collective efficacy.

Enhancing Principals' Adaptive Leadership Capacity

Rodrequez and King were particularly committed to enhancing principals' leadership capacity. They focused on improving principals' ability to facilitate shared and distributed leadership through developing school-based leadership teams and refining the school-improvement planning process. Building effective school-based leadership teams often requires such teams to redefine their purpose. For instance, rather than serving solely as a communication vehicle for the school, the leadership teams' purpose becomes leading the improvement of teaching and learning. Redefining the purpose frequently compels a move away from traditional representative-based membership structures (e.g., grade or departmental representation) to membership based on an educator's leadership qualities and ability to challenge the status quo and spearhead change.

Holding higher expectations for ourselves and our students takes courage; we must often push back on our own beliefs.

Daniel Scherer, principal of Meadowmere Elementary in the Grandview district, was strategic in selecting his leadership team members. He developed an application process that ensured prospective members had given serious consideration to the reasons they wanted to be on the team and the strengths they'd bring to the task. Scherer's goal was for this team to have a cohesive vision of good teaching and consensus on their goal. He and the leadership team engaged the school staff in developing a teaching continuum that articulates their common vision as a school and can be used as a tool for ongoing dialogue about the gap between current teaching practices and the school's desired vision of excellence in teaching.

Encouraging shared leadership by refining the school improvement planning processes was particularly important in Grandview C-4. When Rodrequez arrived in the district, the school improvement plans were "45-page documents that no one paid attention to … the principal wrote it and put it on a shelf." We introduced tools and processes from Improvement Science (Bryk et al., 2015) to strengthen the process used to develop improvement plans in the district. Rodrequez and King redesigned the school improvement planning template to align with the improvement science processes and short-term planning calendars delineated in 30-/60-/90-day timeframes. Principals, working with their leadership teams, used root cause analysis and driver diagramming to determine how they would tackle problem(s) of practice connected to their improvement goals. They engaged in Plan-Do-Study-Act cycles. For instance, Principal Samantha Dane and the leadership team at Belvidere Elementary identified low student engagement as a root cause for the school's academic performance and determined a key driver of change could be implementing student goal-setting schoolwide. Using various tools and a protocol for interviewing students, Dane and the team monitored progress and provided adaptive leadership to further embed student goal-setting.

Reflecting on how principals' capacity has been strengthened, Rodrequez noted, "Principal's presentations to the board this past year were the best I've seen. They were more confident … they understand it more—tracking their progress and the adjustments they were making. They're deliberate … on seeing where they want to go."

Reversing Historic Trends

Three years ago, Grandview C-4 district leaders chose to launch a systemic initiative to raise expectations of their students and themselves and build the leadership capacity necessary to cultivate collective efficacy. While the district has enhanced its targeted interventions for students who needed additional support to learn, they are more appreciably tackling inequity in students' opportunity to learn and achieve by improving teaching in every classroom. This work has better positioned Grandview C-4 for success. Superintendent Rodrequez summarizes:

I am trying to show that our kids can learn. It comes down to leadership and it takes more time than you think. … There are a lot of things we can't control, but we can control us. We can control how we react to situations and how we adapt. We can control how well prepared we are. We can control how well we teach every student.

Can any high-poverty district build the capacity to provide equal opportunity for all students to learn, and reverse historic trends of underachievement? We think so. It's beginning to happen in the schools of Grandview C-4. This analysis of the district's initial phase of improvement, during the challenges posed by the pandemic, provides a compelling case for other high-poverty, underperforming districts or schools to choose to do the same.

Turning High-Poverty Schools into High-Performing Schools

In this second edition, Parrett and Budge show how schools can disrupt the adverse affects of poverty and support students in ways that enable them to succeed in school and in life.

Reflect & Discuss

➛ In considering the specific improvement strategies outlined, where do you think your school or district has the most room for growth?

➛ Can you think of examples in your school or district when the “blame game” or low expectations have hampered improvement efforts? How might you address them in the future?

➛ Why do you think distributed leadership is so critical to efforts to improve high-poverty schools?