The decision was made. Our staff had voted to accept the superintendent's offer to try a new approach to school decision making: site-based management. As with any innovation proposed in a school community, I met the prospect with both enthusiasm and concern. Our small elementary school was working well. The Ralph S. Maugham School's reputation for academic excellence, creativity, and a spirited, involved, and dedicated staff was widely acknowledged. Why should we tamper with something that was working well? How would my role as the principal change?

Frankly, I was pleased with the degree of sharing that was already established in the school; I also enjoyed the prerogative to make important decisions on my own, knowing full well that the staff expected everything would fall into place. Somehow, they didn't seem to want to be bothered with the intricacies of the hundreds of decisions made every day. I was a bit worried. Isn't site-based management most often recommended for troubled schools that require major restructuring?

Learning to Let Go

Tenafly, New Jersey, is a well-to-do suburban community of approximately 13,500 residents located within a few miles of New York City. The community has consistently demonstrated an active interest in, and willingness to support, quality educational programs. Our public school district consists of four elementary schools, one middle school, and one high school.

My own leadership style can best be characterized as organized and responsive. I had made countless arrangements to ensure that the school ran smoothly and stayed on an even keel. To the degree that I could provide assistance to teachers and take care of their concerns, I felt that I was fulfilling the role of an involved, active principal. As my experience with site-based management unfolded, however, I found that I needed to learn to let go and provide the means for people to solve their own problems.

This process of “letting go” can be likened to a tightly wound watch spring. As we moved toward site-based management, I had to let it unwind incrementally; with each release of the spring, new potential and energy was realized. The rewards for all of us soon became apparent.

Charting New Paths

- four teachers: one from a primary grade, one from an intermediate grade, one specialist, and one additional teacher at large (if possible, a nontenured teacher);

- three parents: representing both those who are actively involved in our parent organization and those who are not;

- the school principal;

- a noncertified staff member (secretary, aide, or custodian);

- a member of the board of education;

- a central office administrator.

Then, in a self-directed meeting, the school staff elected representatives to the council, the parent body followed a similar procedure, the superintendent appointed a central office administrator, and the school board president selected the board member representative.

Lesson 1: Learn to Listen

In the fall, we held our first meeting as a school leadership council. Bena Kallick, our district's consultant for site-based management, was the facilitator. Through our involvement with her, we learned many of the skills and techniques associated with site-based management. More important, we learned them within the context of our own deliberations—not in isolation from real problems.

Our first step was to develop a school philosophy. We worked in cooperative groups, employing and practicing the techniques many of us had learned to use in classrooms. In the process, one of the most important lessons we learned is that in order to really listen, you must move beyond simply hearing the content of what is said. You must hear some of the emotion, concern, and passion with which points are made. I discovered that by paraphrasing what someone is saying and checking whether my understanding matches the intention, communication is clarified for both parties. As a result, I heard some teachers in a new way for the very first time. What an insight!

Lesson 2: Establish Patterns for Communication

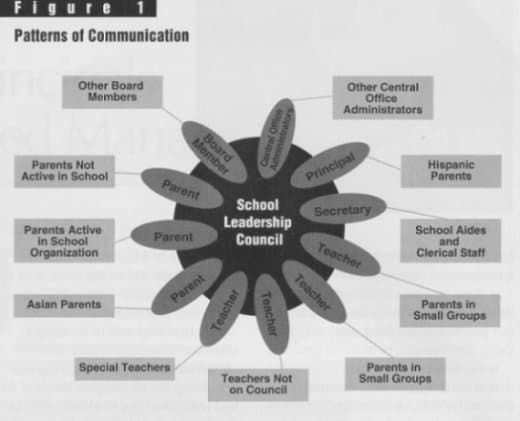

Defining a school philosophy became a significant task for our fledgling group. After producing our first draft, council members volunteered to meet with 7 to 10 members of the community to share our efforts, check whether our beliefs were consistent with their views, and then report results to the council. Some teachers met with other teachers who were not members of the council; other teachers met with parents; some parents met with non-parent citizens; the secretary met with our clerical staff; the board member interviewed other board members; and I chose to work with our growing Hispanic community (see fig. 1).

Figure 1. Patterns of Communication

Through these interchanges, we listened to the ideas of others, refined our perceptions, became attentive to our audience, and raised our collective consciousness about what a school philosophy means. In order to represent the collective thinking, we synthesized the various viewpoints into statements about our values as a school community.

Lesson 3: Understand Individual Styles

The format of the meetings to gather community input took several forms, from informal conversations to more structured discussions. Two teachers invited small groups of parents to early morning coffees. Another staff member interviewed all the school aides after lunch. One teacher laid out a folder containing our working draft in the faculty room and asked for feedback.

- We strive to provide a nurturing environment in which all children can flourish, enhancing their self-worth.

- We strive for academic quality in a stimulating school environment.

- We value close ties among children, staff, parents, and the community.

Lesson 4: Promote Open Communication

As the council met throughout the year, we learned how to process information and feelings in group work by “freezing” a statement to seek further clarification and more open communication. By acknowledging the emotion behind a member's remarks, we found that our discussions took on a new freedom and honesty.

Previously, during such interchanges, I had attempted to protect group members by trying to keep feelings from surfacing that might be hurtful or impede our progress. What I learned, though, is that such feelings must be aired. We found that by expressing and dealing with divergent opinions, we made far more progress than by trying to minimize them. Teachers began to face one another without my intervention.

Lesson 5: Work to Build Trust

A new level of trust began to develop within the group. Before long, we were taking turns leading the meetings, exercising our skills in setting agendas, assigning roles (facilitator, recorder, timer, and process observer), and evaluating our progress. Divergent ideas resulted from brainstorming sessions in an atmosphere of mutual respect. Reaching consensus, we discovered, does not mean total agreement, but rather a willingness among all members to accept a decision.

As we refined our decision-making processes, we began to see the connections among the various tasks we were tackling: determining our school philosophy, analyzing sources of frustration, defining priorities, and generating alternatives. We assumed ownership for our individual assignments and reported findings of our own “research” to the entire group. One of the more important and broadly felt realizations was that we looked forward to our meetings and to the sense of accomplishment shared. We truly enjoyed our times together.

Lesson 6: Think with New Perspectives

One of the important issues presented to our council mid-year was the frustration staff members felt within a busy, stressful day. The parade of classroom interruptions, pull-out programs, and short, unproductive spurts of planning time—all contributed to a feeling that staff members longed for more “quality time.” In light of the daily demands on student and teacher time, I might have thrown up my hands, deemed the problem impossible to solve, and then felt thwarted by not being able to provide any relief. But, this time, I held back for a while.

In our council meetings, we focused on the tempo of our teachers' day, contrasting this with what we considered to be quality time in our own lives. Council members wrote about what the concept meant to them in their personal lives, and students described their notions of quality time. Before long, we began to see how we might build more quality time into our days. For example, we knew that we enjoyed our times together as a staff solving problems, sharing joys and sorrows, and providing professional and personal support for one another. We then looked for time within our day that could be used to foster what we valued.

One solution was to schedule our monthly faculty meetings early on Monday morning, instead of in the afternoon. In this way, we would be able to use the large chunk of time, in the afternoon, to address faculty concerns: sharing new book titles for our literature-based reading program, talking about individual youngsters who might pose a particular challenge, or dealing with other matters brought directly from the staff. Certainly, some compromises needed to be made. The early morning meeting would allow less time than our traditional after-school faculty meetings. However, we found that many teachers are more attentive and forthcoming with fresh ideas at this time. While we may not have actually gained more time for staff deliberations, we found new frames of reference for faculty meeting times. And we might never have arrived at this happy arrangement had we not learned to look beyond the school walls to gain new perspectives about perceived problems.

Lesson 7: To Promote Autonomy, “Let Go”

It had been my usual practice to send memos to remind staff about meetings and commitments as a date or deadline approached. When it came time for us to experiment with having an early morning faculty meeting, I felt certain that several people might be late or even forget about the new time. Since this was a council decision, however, I was advised to leave it to the members to apprise their colleagues of our new format.

When individuals feel that they are a part of a decision, they assume more responsibility for implementing it than if the decision is made for them. This may sound like a simplistic observation, but when you see it for yourself, there is an important lesson to be learned. If you want to promote an autonomous staff, then you must allow things to happen without checking every step of the way. As the members of our council sensed a growing control, their commitment and enthusiasm for their work together grew.

Lesson 8: Take Time for Self-Reflection

Self-analysis and reflection proved to be an invaluable outcome of our one-year experience. Through our deliberations, I learned to examine my own leadership style. For example, I realized that I had become quite comfortable accomplishing many tasks in isolation—from scheduling to budgeting to planning for program implementation. Now there was a new mechanism available for gaining staff and community input into decisions that might have a significant impact upon the school.

Through our deliberations as a council, I developed a better appreciation of the frustrations and perceptions of our staff members. I became more empathetic about the time pressures they felt. I also examined my relationships with staff and my own reluctance to delegate tasks. In the past, I had always tried to jump in and solve problems for teachers, rather than empowering them to feel that they might possess the solutions. My own desire to be responsive may have impeded others at school from assuming leadership functions.

The Added Benefits

With a move to site-based management, decisions may be a little slower in coming, but they will be more enduring. Staff members who may have been reluctant to assume responsibility—feeling “it's the principal's problem, not mine”—will feel a part of the process. With the realization that their input is valued comes a new sense of commitment. The process of site-based management also allows the principal to assume a new level of involvement, seeing situations from the vantage point of others.

The process requires self-examination, role analysis, and meaningful reflection. Working with a school council in a participatory fashion helped to free me from the loneliness that often accompanies leadership. The experience also led to new understandings about human and group dynamics, as well as a compelling legitimacy for solving problems in a collegial fashion.

As principals wend their way through the many passages of site-based management, there will be moments of confusion and frustration. There will be times when you think you're losing control over time-honored prerogatives. But take it from one who has been there. Any perceived drawbacks pale in comparison to the substantial benefits of the approach.