Henry David Thoreau once said, "It is not enough to be busy. … The question is what are we busy about?" As Thoreau reminds us, how we spend our time is a function of our values—and how time is allocated during the school day reflects what is important to the community, intentionally or unintentionally.

In the past two years, schools have faced the herculean task of attending to students' physical and mental well-being while attempting to engage them in meaningful learning. Educators have added vital resources and tools for students and school staff, such as social-emotional learning programs, increased counseling and clinical support, and incorporating coping strategies like meditation and breathwork into the school day.

These resources and tools can be very powerful for many individuals in building and helping them maintain their sense of well-being. However, an important aspect of improving and sustaining the well-being of an entire school community is also to make changes at the system level. In times of chaos and uncertainty, people crave stability and security. The use of time in school has the potential to shape the quality and the quantity of the experiences students, staff, and families have each day with each other and individually.

What Do We Need for Well-Being?

If we turn to self-determination theory to help us understand how to support positive physical and mental health for people of all ages, life experiences, cultures, and backgrounds, we can see that human beings have a universal need for autonomy, competency, and relatedness. People are more likely to feel a sense of well-being when they can make decisions that are aligned with their interests, feel a sense of mastery and purpose, and are connected to others (Chirkov et al., 2003; Ryan & Deci, 2001).

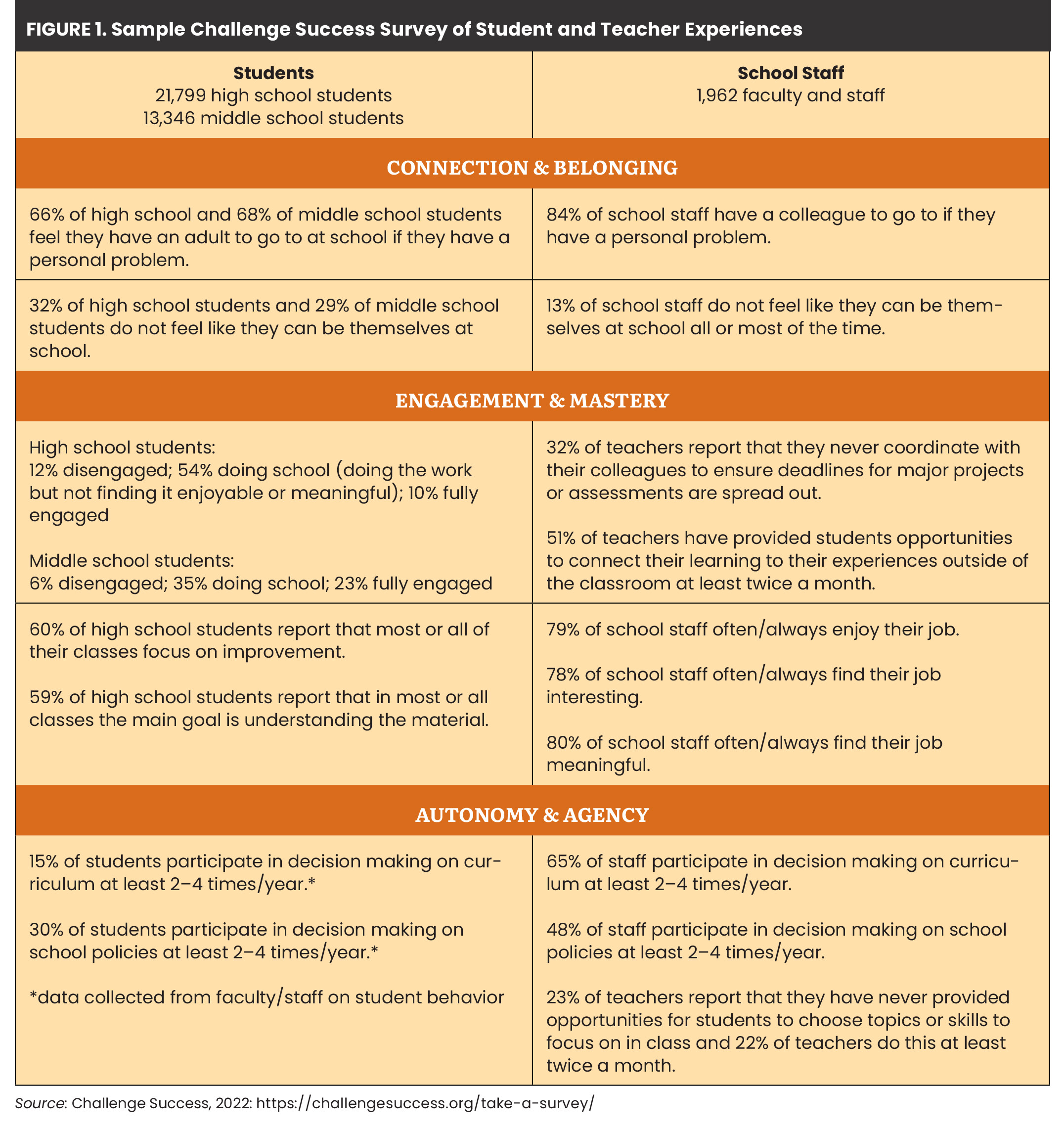

Over the past 15 years, we at Challenge Success, a nonprofit school reform organization affiliated with Stanford University's Graduate School of Education, have conducted student, faculty and staff, and parent surveys with school communities to dig deeper into well-being and engagement in schools. Through these surveys, we glean important insights into the areas of well-being that may be working well for students and staff, as well as those that may need to be strengthened. We share our analyses with school teams and discuss the implications of the findings on school practices and policies. In times of chaos and uncertainty, people crave stability and security.

Findings from our 2021–22 school year surveys, revealing the effects of pandemic-related disruptions on students, show a need for schools to make changes in areas specifically related to autonomy, competency, and relatedness. In our work with schools, we share school-specific data similar to that in Figure 1 to inform our discussions with school leaders about the importance of supporting student and staff connection, engagement, and autonomy. In our experience, when students and staff do not feel like they can be themselves at school or do not have a trusted person to turn to when they have a problem, it suggests educators need to increase focus on school belonging and connection. When students are not engaged with their classes or feel like their learning focuses more on performance and less on improvement and understanding, and when teachers report fewer opportunities to connect learning to the real world, this represents a potential problem with overload and lack of time to promote mastery. And when students and staff feel like they are not given ample opportunities for voice, choice, and decision-making in schools, this points to a need to increase autonomy and agency.

The Schedule: Reflecting What's Important

While there are many levers in a school system that impact student and staff well-being, the school schedule impacts all stakeholders at the school on a daily basis, making it an essential component in addressing the well-being of the school community.

When we talk about the "school schedule," we are referring to multiple levels of time spent during the school day. First, there is the schedule that occurs between the start of the school day in the morning and the end of the school day, including after-school activities and meetings. Then there is the cadence of the school year—the start and end, when breaks and exams occur, as well as other considerations about the use of time. Though some aspects of the school schedule may not be within a school's control, the design of any schedule is ultimately a reflection of the school community's values and priorities. Opportunities abound to restructure big and small increments of time in schools so the schedule aligns more appropriately with educators' goals to create healthier youth and adults.

So how can schools use the school schedule to deepen connections, promote greater autonomy, and allow for more experiences of mastery and deep engagement? The examples we share below come directly from our work at Challenge Success with middle and high schools during this challenging year.

Using School Time to Deepen Connections

The organization of time in the school schedule can facilitate or impede connections between and among the school staff and students. Here are some ways we have seen schools use time to deepen connections and foster greater belonging:

Lunch periods. Today, not all schools have a designated lunch period, while many that do don't allow sufficient time or protect it as necessary down time. Ensuring that students and adults alike have a specific time for lunch allows everyone to take a break, slow down, see friends, and "break bread" together. It places a value on stopping to fuel your body and allows for more peer-to-peer, and student-to-faculty connection.

Time for advisory. High-quality advisory programs, where small groups of students meet regularly with an adult advisor, can foster students' need to feel known. They can be "safe spaces" for students to share struggles and support each other. Typically, the most effective advisory programs follow either a formal or informal curriculum plan that includes sample lesson ideas and intended outcomes, as well as some professional training or a guidebook for all advisors prior to the start of the school year on how best to support students' well-being. Advisory can meet daily or weekly, but the bell schedule should allow ample time (between 20 and 60 minutes, depending on frequency) to ensure meaningful interaction. Some schools have converted the "old" homeroom concept into effective advisory time, but it needs to be longer than the typical 10-minute homeroom that is mostly used to take attendance or listen to announcements.

Tutorial or office hours. Many schools offer a tutorial or study hall period during the day to allow greater access to teachers and other supports.

Well-Being in Practice

After noticing how few students interacted at lunch or even took breaks during the day, one Challenge Success high school changed its bell schedule to allow for students to share a common lunch period with a diverse mix of their peers. Before this change, students had no formal lunch time—they just squeezed in lunch whenever they had a free period (and some of them didn't have one!). A common lunch period promoted a stronger sense of belonging and connection, allowed students time to eat with their friends, and created space for planned activities at lunch that attracted a much higher percentage of students. As the principal shared in one of our surveys:

We didn't have a lot of student culture [building] during lunchtime. In fact, it was a little bit of a ghost town. [The change in schedule] forced them to use those minutes for lunchtime to just relax and to be with their friends, rather than continue their day and do their homework. It helped our culture quite a bit because now we have student activities at lunchtime.

In another schedule change, schools conducted "connection audits" in which they matched staff to students with whom they already had a strong relationship. These connection matrices often revealed which students might be in danger of falling through the cracks. Schools used advisory time to ensure these students could have more frequent and consistent interactions with a caring adult.

Well-being in school doesn't just happen; it has to be made a priority.

Time for Mastery and Engagement

Students and adults need time during the school day to focus, to practice what they have learned, and to reflect. When they have short class periods with little time between classes, they are less likely to experience multiple modalities of teaching and learning, ask questions, or find time to reflect on their learning. As a result, their sense of mastery and academic engagement may suffer.

Some ways schools might find time to give students these opportunities to reflect and solidify their learning include:

Longer class periods. Longer periods allow for varied modalities of instruction and learning, such as individual work or group time. Mastery learning requires reflection and opportunities for questions. Typical class periods often deprioritize these aspects.

More time between classes. It is exhausting to switch gears from one topic and group dynamic to another. Schools can incorporate adequate time for students and teachers to make those transitions and slow down the pace of the day.

Test and project calendars. Students often complain that they are "slammed" with tests and due dates on certain days or weeks. A calendar for major assignments and assessments in each course can reduce overload and emphasize mastery by allowing sufficient time for students to study and prepare.

Later school start time. Later start times for school account for adolescents' circadian rhythms and allow them to experience morning learning while in a more awake state. This is also a good reason to alternate which classes students attend first period and to eliminate a "zero" period, a class which is offered before the start of the school day.

Well-Being in Practice

Several Challenge Success schools have noted that the pace of their school day was contributing to student and staff stress. They made simple yet significant changes by expanding the time between classes known as the passing period. Some schools lengthen passing time from 5 minutes to 8 or 10, while others try to reduce back-to-back classes by incorporating breaks, lunchtime, or advisory in between, which can reduce the amount of passing time needed in the school day. While it's admittedly complicated to try to find any extra time in an already-packed academic schedule, these changes decrease the "hustle and bustle" of the day, decrease disciplinary issues in hallways, and increase instructional time because students and teachers are more settled when class begins.

As one principal shared, "As minor a tweak as [having longer passing periods] seemed to be at the time, it has changed just how our kids feel and act on campus." Another said:

We had a two-minute passing period. Kids would burst out the doors, they would run to their next class. There wasn't time to use the restroom or to get a drink of water or say hi to their friends. It was just, move! And even us, as the adults, were like, "Come on, you guys, you can make it." [When we extended the passing period] we talked to the students and said, "We're doing this so that you have less stress and [more] time to do what you need to do. You have time to breathe between classes and make that cognitive shift, maybe from science to history." Everybody was able to really de-stress. We had a lot less tardies, not surprisingly.

When students and faculty can control how they use their time and have opportunities to make decisions and choices aligned with their needs and interests, they are more likely to thrive. Healthier schedules prioritize choice in courses whenever possible and time for extracurricular activities without trading off student and staff sleep. Students and staff value free time during the day where they can choose how best to spend it.

Some elements of the school schedule where educators might better promote agency and autonomy include:

Electives. Electives give both students and teachers the freedom to choose to take or teach what they are interested in and enjoy doing.

Extracurriculars. Many students participate in extracurricular activities primarily for intrinsic reasons, and participating in extracurriculars can be linked to well-being. However, we do know that "too much of a good thing" is a real possibility. It is important that practices and meetings are not occurring late into the night or early in the morning.

Flexible time. Free periods allow students and staff the ability to prioritize meaningful tasks without the need to wait until after school hours to get homework, grading, or prep work done. Some schools require students to physically be in a classroom during flex times to have them count toward instructional minutes; other schools find ways to account for instructional minutes via longer course periods and electives, thereby allowing kids to spend flex time wherever they want.

Weekends and breaks. Rest and recovery are essential parts of learning. No-homework weekends or breaks, as well as scheduling exams before breaks (as opposed to after) are examples of practices that emphasize rest and recovery.

Well-Being in Practice

Another change students and parents report appreciating the most are homework-free holidays or weekends. These schoolwide policies communicate support for what we call PDF: playtime, downtime, and family time.

As this middle school principal shared, a little goes a long way:

We began exploring the concept of homework-free nights as recommended by Challenge Success. We tried several last spring, and you would have thought that we were handing out gold candy bars. Parents and students that are hard to impress were like, "This is genius!" That's been a huge game-changer for us and an easy win, and the students felt heard.

Another school district recognized the need for students and families to have a break over holidays. School leaders sent the following message to emphasize why they were promoting the break from homework:

Our high school faculty have made a commitment to support well-being. We will not be assigning homework this year for Thanksgiving, winter, and spring holidays. The hope is that students can take this opportunity to spend time with their families, work on hobbies, read a book for pleasure, and/or finalize college applications. We are very excited about this proactive approach to reduce student stress and workload. Enjoy your time!

A Key Lever for Well-Being

Well-being in school doesn't just happen; it has to be made a priority. How we use time in schools can be a key lever to promote whole-school-community well-being—particularly at this moment of heightened chaos and uncertainty. The schools we work with have found success with both large and small changes to their school schedules to emphasize well-being for everyone. Promoting ample time to build strong connections, allowing for meaningful work, and increasing student and teacher agency and choice is all time well spent.

Reflect and Discuss

➛ Does your school's schedule reflect well-being as a priority? Why or why not?

➛ How does time affect your own well-being—either positively or negatively?

➛ Do any of the schedule changes the authors mention seem like a doable option for your school? Which might be most effective in your setting?