Joanna Schaefer and Javier Vaca often combine their two history classes so that students can observe how historians wrestle with ideas. As Ms. Schaefer says, "When Mr. Vaca and I are in the room together, we can have a conversation that's similar to what historians really do. We consider different perspectives and respond to the statements that the other person makes. It's really a give-and-take. We hope that as our students experience this, they'll naturally start thinking like historians on their own."

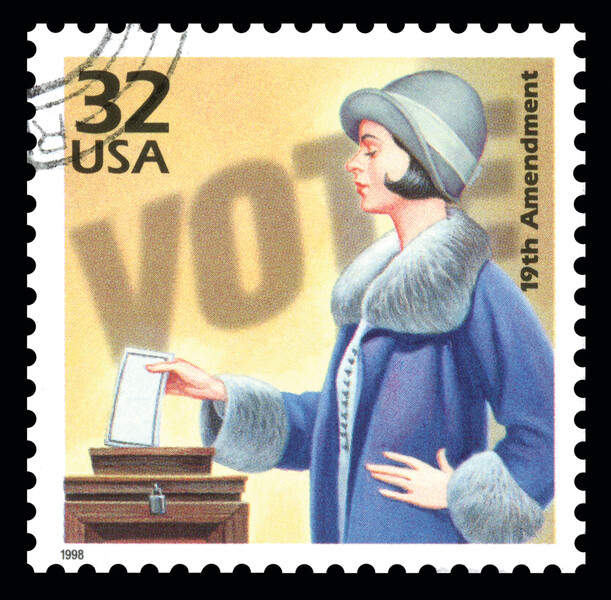

In the video that accompanies this column, we visit the teachers' combined 11th grade classes and observe as they demonstrate for students how historians explore primary sources. As part of this lesson, the students examine three documents related to the struggle to obtain voting rights for women in the United States in the early 20th century. The two teachers model their analysis of the first document (an advertisement depicting the vote on women's suffrage as a choice between "the home or the street corner for women").

Students collaboratively read the second and third documents: a 1912 article from an anti-suffrage newspaper, The Woman's Protest Against Woman's Suffrage; and congressman John A. Moon's speech in the House of Representatives on January 10, 1918, in which he played on both racist and patriotic sentiments to oppose suffrage. By the end of the class, students are ready to write with a new understanding of the views that were mainstream at a specific point in history.

Ms. Schaefer and Mr. Vaca are demonstrating a powerful strategy for teaching disciplinary literacy—teacher modeling. To make the most of this strategy, teachers need to do two things: understand the specific aspects of thinking in their discipline, and make sure to turn the thinking over to students.

Understand the Thinking in Your Discipline

As several articles in this issue have noted, thinking like a historian is different from thinking like a scientist, a literary critic, a mathematician, an artist, or a fitness expert. As teachers model, they should consider these differences and plan for students to be apprenticed into the specific thinking of their discipline. For example, when analyzing literature, professionals look at such elements as

Author's craft (the choices an author made, including genre, type of narrator, and literary devices).

Theme (the underlying message or big idea that indicates the author's belief about life, as well as how this message relates to universal themes that transcend culture and language to explore the human experience).Historians, in contrast, are more likely to engage in such cognitive practices as

Sourcing (examining who produced the document and how that source affects the document's viewpoint and reliability).

Corroborating (reading across multiple documents to identify points of agreement and disagreement).

Contextualizing (considering the document in historical context, including when it was written, where, and what else was happening at the time).

Ms. Schaefer and Mr. Vaca focus on two of these disciplinary practices as they model how to think like a historian: sourcing and contextualizing. They also demonstrate more general literacy tools, such as annotating and asking questions. As the students work collaboratively, they engage in the same processes their teachers used, but with different texts. Over time and with practice, discipline-specific thinking becomes a habit.

Encourage Students to Think Along with Teachers

Teacher modeling should not become a teacher monologue. Rather, students should be encouraged to think along with their teachers and periodically contribute to the discussion. You'll notice that Ms. Schaefer and Mr. Vaca model for a few minutes on one short piece of text, and then provide students with a chance to engage in collaborative conversations about two other pieces of text. As students read and discuss the new texts, their teachers move from group to group asking clarifying questions, pressing for evidence, and checking for understanding.

Their lesson would have been very different had the teachers chosen to model their thinking about all three pieces of text. In fact, it would have been boring. It would likely not have resulted in students learning more about the disciplinary aspect of history, much less the reasons that many Americans once believed women should not vote.

The modeling these teachers provide for their students is brief, focused, and relevant. They hold their students' attention while they share their thinking. When this type of disciplinary thinking aloud becomes part of the classroom routines, students come to know that they'll get a glimpse inside the thinking of their teachers, but will then be expected to try these types of thinking for themselves as they learn.

Apprentice Historians

Of course, modeling is just one instructional strategy that teachers need to use to help students become disciplinary thinkers. Students need to be engaged in a wide range of complex tasks that require them to apply what they've learned, both in terms of generic literacy skills and more disciplinary-focused skills. Having said that, we believe that modeling is an important aspect of students' disciplinary learning because it provides them with opportunities to be apprentices as they read, write, discuss, and think about the wide range of ideas and opinions found within the study of history.

EL Magazine Show & Tell / February 2017