Tyler sits at his desk, sketching the bridge looming outside his school. His 3rd grade teacher moves from student to student, helping each one better understand the math assignment Tyler has already finished. Peering out at the bridge, he wonders how it's built. He sees a traffic light and wants to ask how it automatically changes colors. But his questions will go unanswered.

Tyler's need for higher-level challenge is unmet, drowned out by the drumbeats urging his school's teachers to focus on students who require intensive assistance to bring their skills up to grade level. This year, he may still strive for excellence in the classroom, despite his boredom. But by 5th grade, he may stop trying.

Tyler is just one of 3.4 million high-potential, low-income children throughout the United States whose plight has been largely ignored, according to the first nationwide analysis of high-achieving students from poor families. That study, Achievement Trap: How America Is Failing Millions of High-Achieving Students from Lower-Income Families, found that nearly half the low-income students who rank in the top quarter of their class in reading in 1st grade fall out of that rank by 5th grade. Their chances of remaining high achievers throughout high school and graduating from college are lower than those of their similarly talented but higher-income peers.

So as a student like Tyler moves from elementary to secondary school, his motivation and effort are likely to move down. He may fall into the achievement trap. As the study's authors explain,The quandary facing the 3.4 million high-achieving lower-income students is that, at every step of the educational process, they face significant obstacles to continuing their high levels of achievement. They have the ability to excel in college and achieve the highest levels of success in their chosen fields, but they are less likely to have the social and financial resources necessary to get there. That these facts are so little known has helped to perpetuate a general public attitude that these students either do not exist in appreciable numbers or are continuing to succeed in their current environments. (p. 34)

The problem is dire in the inner city, where obstacles to students reaching their potential include limited life experiences, a lack of books and insufficient exposure to books, and a lack of both accessible libraries and stimulating summer experiences. Unstable families, incarceration, threats of violence, and the lure of the streets abound. Less academically rich conversation and vocabulary characterize many home environments, and the lack of consistency in language and behavior between school and home often creates challenges for students.

These obstacles persist and often worsen in the higher grades, leading to serious problems by high school: 47 percent of high schoolers in U.S. cities drop out. The average graduation rate of the 50 largest U.S. cities is well below the national average, and there is an 18 percentage point gap between graduation rates in suburban schools and those in large urban schools. So in a sense, every year is a transition year for low-income youth trying to maintain top achievement. Although policymakers are making efforts to reverse poor achievement among low-income students, they are doing little to support high achievement in that same group.

Supporting Our Young Scholars

At Gesu School, a K–8 independent Catholic school in Philadelphia, at which 75 percent of our 460 students come from low-income families, we're attacking this problem through our Youngest Scholars program. We provide remedial instruction to many students who read at least two years below grade level, but we also address the needs of our higher-achieving students. This hands-on, cross-curricular program challenges high-ability, low-income students to develop such 21st century skills as critical thinking, team building, research, leadership, and public speaking through a specially themed summer session and enrichment opportunities during the school year.

Having operated programs to prepare high-achieving middle schoolers to transition to selective high schools, we have learned something about lifting up students who show exceptional promise. By setting high expectations and providing advanced instruction at even younger ages, we believed we could hook talented students on learning and give them the boost they needed.

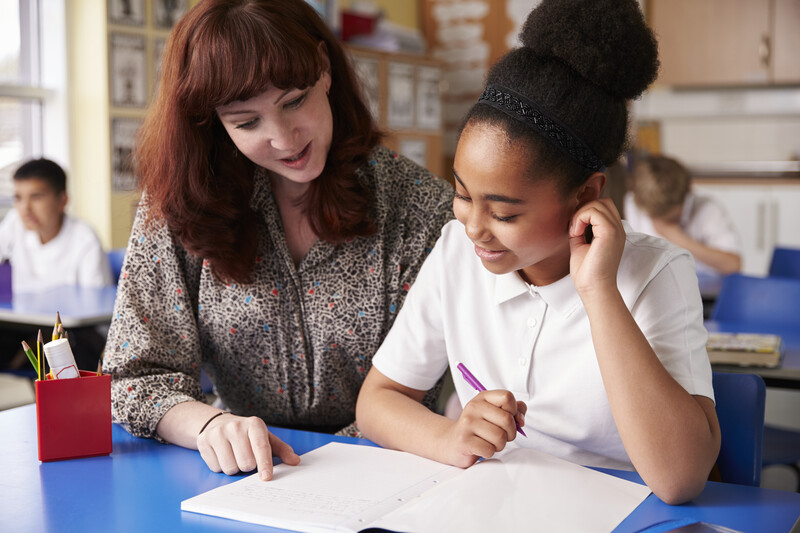

In spring 2008, our principal, Ellen Convey, identified 24 students in 3rd through 5th grade whom their teachers considered very bright and who met the criteria of low household income and the highest scores in their class on the Terra Nova achievement test. Colleen Comey, a special education teacher at Gesu, created a theme-based curriculum using flexible groups that would explore content in more depth than we found possible in the regular classroom.

The pilot program debuted that summer with a five-week session led by Comey and a teaching assistant from the University of Pennsylvania. Students attended five days a week, for six hours each day. Each week focused on a theme—such as Colonial America, ancient Egypt, and ocean life. Most of the students who started in Youngest Scholars as rising 3rd graders are still with the program.

Through direct instruction, independent work, cooperative activities, projects, and field trips, our scholars are exposed to new ideas and develop skills that enable them to stretch their eager minds and learn independently. In summer, students work in small groups, and the learning format includes interactive stations tied to that week's learning module. Students research a topic related to the week's theme, check their facts against multiple sources, summarize in their own words what they've unearthed, and present their learning to the class in creative ways. Regular public speaking sessions involve memorizing and reciting poems, acting out scenes from short plays, and presenting personal narratives.

The students are not graded on enrichment activities, so they feel comfortable trying new things (although we do use a point system to reward desirable behavior and problem solving). As Comey, who now serves as program director and teaches in the weekly after-school session, notes, "Creating an atmosphere of fear and negativity shuts the brain down. But these children know they are safe and surrounded by adults who care about them and their success."

During the school year, young scholars continue to pursue enrichment through weekly after-school sessions with Comey and occasional trips. Many of Comey's sessions focus on students' writing. She presents a general question, such as one related to a societal issue, and students express their individual ideas. Students construct written responses to open-ended questions, sometimes using strategies such as TAG (Turn your thought about the question into a statement, Answer the question, and Give the evidence to support your answer). They also attend weekly pullout sessions with a volunteer specialist, Rosalee DiIulio.

On the basis of their individual interests, DiIulio assigns students a classic or modern novel above their grade level to read independently. They respond to the novel through summaries, discussion, and writing that explores vocabulary, character development, and story elements. Then, in college seminar fashion, students meet in small groups to discuss and compare characters, plots, themes, and "big ideas" in their novels. Our scholars act out scenes and connect themes to their own experiences; they also solve Mensa puzzles and give on-the-spot speeches based on a prompt. Comey and DiIulio regularly communicate with our teachers and principal to ensure students' need for challenge is being met.

Feeding Hungry Minds

One of the greatest initial challenges has been teaching the students both how to work independently and how to collaborate in small teams. Over time they learn how to bring out the best in themselves and one another. They appreciate the chance to think about each learning activity and consider how they might do it differently to deepen learning.

As DiIulio observes,I've seen how hungry they are for more— more stories, more critical thinking. Whether we use fairy tales, fables, classic novels, or popular books like the Percy Jackson series, we're sparking their creative juices. … They now understand how to think outside of the box instead of just regurgitating information.

Watching Them Thrive

Although we haven't yet quantitatively measured the program, we clearly see students thrive, thanks to Youngest Scholars. Derrick, a 5th grade boy who has been with the program since its inception, is highly intelligent but was more comfortable approaching problems independently. At first, he was frustrated with group projects, especially when he realized his reactions were slowing the team down. But as he spent more time in team building and cooperative learning, he learned new strategies to deal with group dynamics and differing personalities. By the second summer, he was excited to be there, showing up early and asking to take books home; by the third summer, he had become an animated leader.

Caitlin, a rising 3rd grader, was initially very timid, had limited knowledge and life experiences, and was wary of public speaking. Once she connected with the topics, however, she moved beyond her comfort zone. From trying Egyptian food to participating in literature circles to borrowing higher-level books to reread at home, she blossomed. Today she is no longer the quiet one in the group.

We've seen many other low-income students develop greater self-confidence and discover new experiences and learning possibilities—through solving problems, analyzing data, sharing impressions, and connecting ideas. At Gesu, we try to help all students realize their potential by targeting programs to every level of intelligence and ability. But we realize that it's crucial to make sure the intellectual needs of bright, economically deprived students are not neglected—at Gesu or elsewhere. As theAchievement Trap authors say, educators can—and must—do better.

We plan to carry out an impact study of Youngest Scholars. Once we document outcomes and make needed improvements in how we reach students like Derrick and Caitlin, we hope that other schools will look to our program as a model—and that many educators will join us in making sure no child falls into the achievement trap.