Big events lead to big changes. If you spun the Wheel of Historical Events and it landed on World War I, the myriad changes you’d see stemming from that global conflict would range from the breakup of empires to the proliferation of canned food. The attacks on 9/11 forever changed the rules for air travel. The ripples of catastrophe emanate for a very long time.

And then there’s the COVID-19 pandemic.

This pandemic and the shutdown of normal life have been devastating—in lives lost; long-term health effects; unemployment; and copious doses of anxiety and mental health problems, to name a few after-effects. Nor will the upheaval of 2020 leave education unchanged. To start with one positive example, consider how much more fluent educators now are digitally. Some who may have considered “cutting board” to be the best use of a laptop have advanced from learning how to log on to their device to managing breakout rooms on Zoom, Teams, or other digital portals. These kinds of changes, and more, happened for one main reason: We were forced into them.

So despite the devastation the pandemic has caused, maybe we can find some silver linings. People in the past have learned to bring good out of a crisis. Following World War II, when Winston Churchill was helping form the United Nations, he quipped, “Never let a good crisis go to waste.”

Over the past year, I’ve been reminded of this quote often. Churchill was by no means making light of a conflict that took more than 60 million lives—and I’m not making light of the suffering caused by COVID-19. I’m just making the point that we can in some ways emerge stronger.

For instance, the pandemic forced education into our homes—literally. Parents gained a front-row seat to learning outcomes, instruction, and assessment. As a result, families will likely remain more aware of their children’s learning lives.

I’ve also been seeing some examples of “emerging stronger” in changes to instructional practice since school buildings closed in 2020. Because of pandemic-related travel restrictions that made my usual role consulting in different school districts near-impossible, in fall 2020, I found myself back in school administration. I’ve been serving as an assistant principal and teaching one class at Summerland Secondary School in British Columbia. This experience, combined with remote conversations I’ve had with educators around the world, convinced me that the shakeup to how we teach has the potential to positively change ways we approach assessment, assignments, instruction, and grading. Let’s explore a few of these potential changes.

Toward “Non-Googleable” Assessments

Same Question, Different Answers

In April 2020, during a remote PD event with a group of Minnesota teachers, I had a moment that was like an indicator light flashing on a display panel, signaling underlying, long-ignored trouble. One teacher, exasperated about giving tests to students working remotely, commented, “I can’t use my multiple response tests—the kids just Google the answers!” Another participant responded, “Maybe this is a sign we need to change our questions.” She noted that assignments or assessments that stimulate inquiry and make students justify their answers would be more Google-proof.

“Google-able” assessments are problematic when we can’t watch our students directly—but at other times, too. I’m pretty sure Google was around before COVID-19, and I’d wager it’ll be around after. If the integrity of an assessment hinges on making sure kids can’t access that information during the assessment, it’s an indication that the intended demonstration of learning requires the student to merely memorize and recall content.

Assessment Tip

Assessments that stimulate inquiry and make students justify their answers are more Google-proof.

Information and knowledge matter. The question is, if knowledge matters, then what do we want students ultimately to do with it—and shouldn’t assessments reflect that doing? Maybe on the other side of the pandemic we should take that quick-responding teacher’s advice and shift our goal from having kids memorize, recite, and recall to having them argue, justify, and create.

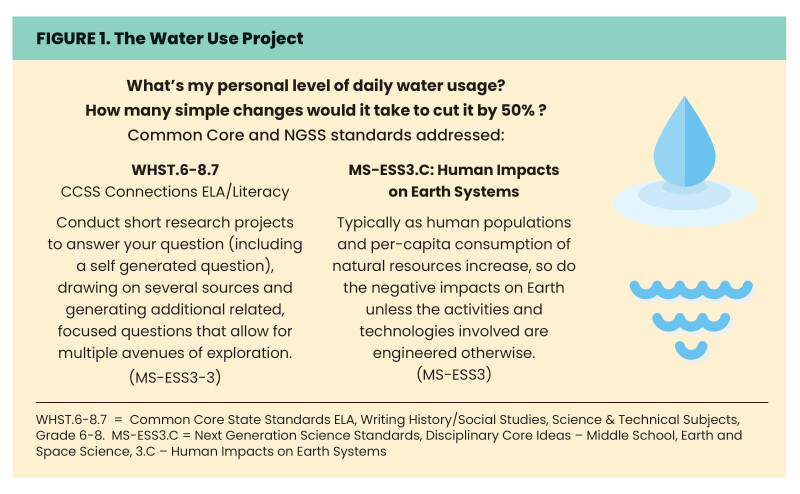

It would also be great to have students use their knowledge to argue, justify, and create in ways relevant to their individual interests or lives. But when shifting to an inquiry- or essential-questions-based assessment environment, it’s not realistic for any teacher to come up with a different question for each of 30 students. But the right question can elicit 30 different responses. Figure 1 shows an assignment used by a teacher in a group I worked with in Minnesota. Note how it addresses Common Core English/language arts standards and reflects the approach of the Next Generation Science standards by using a problem that will be different for each student. Given this type of personalized question—and the challenge of self-generating a second question—it’s very hard for the student to copy off a classmate. It’s virtually Google-proof!

Scaffolding for Success

As effective as this type of inquiry question can be, it’s important to scaffold students toward success as they work with such assessment prompts. Throwing the doors open to exploratory learning with minimal teacher guidance is generally ineffective for learning. Substantial research indicates that when students use pure discovery and minimal guidance, they can easily become “lost and frustrated,” which leads to misconceptions.1

For the water conservation question in Figure 1, we wouldn’t expect students to magically conjure a sophisticated response without having building blocks and tools. The teacher might design a lesson plan around how water use is measured and the tools and conceptual understandings needed to do so. It would be important for all students to have strategies for determining their individual water use when living with others—who also use household water. The class could sample community and global approaches to water conservation, considering how they might apply these ideas to their personal strategy.

Or imagine students are creating a personalized response to the question “Was the American Revolution avoidable?”—what the C3 Social Studies framework calls a compelling question.2 To help students glean important knowledge on the way to forming their unique answers, teachers might guide students in finding answers to supporting questions like “How did the Colonists’ responses inflame tensions?” or “What efforts were made to avoid war?” Such questions let students explore content before they tackle a broader compelling question.

The centrality of educator guidance in exploratory learning should be clear after this year. COVID-19 has demonstrated that students generally benefit from being in schools, learning with and from their teachers. So one goal upon returning to in-person should be for teachers to assess more through inquiry-based questions and use assignments that go beyond one standard answer—while providing clear support and instruction. Perhaps on the other side of the pandemic, effective teaching will be all about balancing guidance with allowing students to learn for themselves.

To be clear, some teachers have been using the kind of inquiry-with-support instructional approaches I’m advocating before COVID-19 and school closures. But the pandemic has highlighted the importance of continuing to move in this direction. With the water project, for example, formative assessments could help in determining whether a student is ready to move from the scaffolding stages of understanding various elements of water conservation to tackling their own inquiry. Less formal methods, like class discussion, might also let the teacher know if students are ready to begin navigating individual inquiries.

Toward Independent Learning

Build Your Own Robot . . . or Revolution

Learning from home, most students had more unstructured learning time. Many teachers turned to project-based learning, having students create a product or do a complex task involving real-life research, like that water-use project. Well thought out projects are a great way to instigate independent inquiry.

Shona Becker, while working as a math support teacher in our district, established goals for how she’d help teachers foster math learning after students entered remote learning. These included assisting teachers in developing project-based learning ideas tied to existing learning standards and designing fun math projects to be done at home with readily available supplies. For example, Shona developed a Build a Robot Project for 6th grade math teachers. The project directions (see Figure 2) clearly connected the robot-building with math concepts, in addition to recommending simple materials. Teachers also pointed students to helpful websites. Students included a picture of their robot that could be shared over a digital-learning platform, and sketched and labeled how they included things like the area of a trapezoid in their creation. They showed the math used to calculate such measurements.

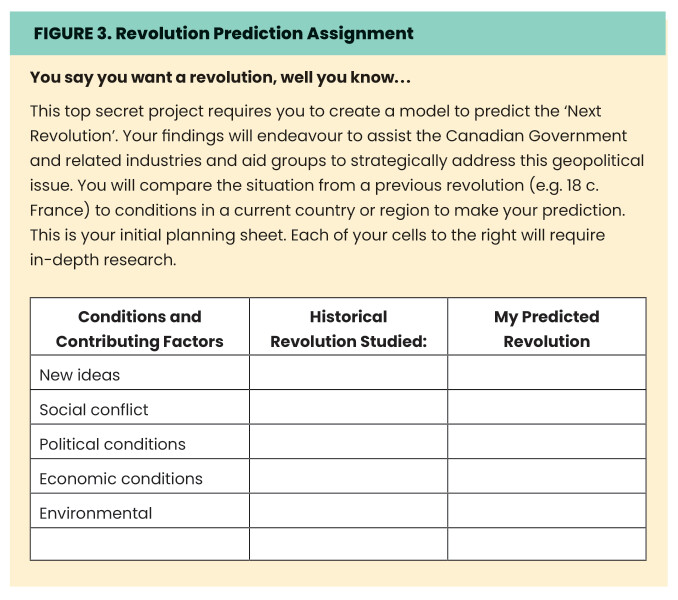

Similarly, through my district role, I supported teachers at Penticton Secondary and helped teacher Russ Reid develop a structure for fostering independent inquiry by connecting content to an engaging thought-experiment task. The assignment, “You Say You Want a Revolution” (see Figure 3), allowed Russ to provide instruction in the content he needed to cover—the underlying causes of the American Revolution and new ideas associated with revolutions—while requiring students to work independently to understand the material in depth. Students then used the insight that content provided them to individually predict where the next revolution might occur. (While this sample assignment connects to history, the structure is usable in many curricular areas.)

In these examples, teachers pinpointed key learning targets for students and established an overarching assignment that included the targets, but the manifestation of the learning differed for each student. This approach to project-based learning could be incredibly powerful in many curricular areas.

Build-Your-Own Inquiry Questions

Another Summerland teacher, Marcus Blair, recognized the powerful potential of inquiry questions and wanted to shift more of the ownership in generating questions to his students. Marcus and I considered the build-your-own pizza approach used in some restaurants: You start with choosing a size, then the type of crust, then your desired sauce and toppings. This upcoming school year, Marcus, a social studies teacher, will try something similar to guide high schoolers in forming their own inquiry questions to investigate topics that fascinate them.

We examined the learning standards in the curriculum and adopted question starters—and other elements of a good query—pointing students to analysis, determining significance, or recognizing cause and effect. He refined his ideas into a Social Studies Question Generator.

This generator is a “menu” labeled “Build your own inquiry pizza—Social Studies version,” featuring three boxes, each box full of many meaningful words/phrases one can select from to develop a rich inquiry. From these boxes, each student chooses four elements they will combine into a personalized inquiry question, building that question by selecting, in this order:

One sentence starter (how does, what makes, how can . . .).

One “catalyst or change agent” (technology, social media, women’s rights movements, global warming, literacy rates...) OR one significant issue or topic (democracy, personal freedoms, habitat loss, Russian foreign policy...), followed by one verb (change, stifle, influence, restrict, illustrate...).

One more catalyst OR issue.

This process yields a unique question for each learner, such as “How does social media influence democracy?” or “How can increasing literacy rates impact women’s rights movements?”

The question is, if knowledge matters, then what do we want students ultimately to do with it—and shouldn’t assessments reflect that doing?

Good Changes to Grading

Better Assignments, Better Ways to Grade

COVID-19 also played a role in leading Marcus Blair to rework how he grades. Like the Minnesota teachers, Marcus noticed that attempting to measure student learning in remote environments clashed with his typical recall-and-recite assessments. So, like them, he shifted to questions students could answer individually, asking students to measure something in their lives, justify ideas, or similar open-ended tasks. Marcus recognized that if the verbs in the work he asked students to do were changing, he needed a better scale to report performance of those verbs. Instead of grading on percentage correct, from 1 to 100, he began grading major assignments with a 4-level scale (emerging, developing, proficient, extending) currently proposed for K–9 schools in British Columbia. One driver for this change is the belief that, as student demonstrations of learning become more complex, involving modelling, creating and designing, descriptions of learning may prove more effective than judging or grading this learning–hence the shift from numbers to words.

In another distance-learning epiphany, Marcus realized that as students learned more independently, some pushed well beyond his expectations. So he re-labeled the upper end of this four-point scale sophisticated, essentially removing the ceiling to the learning. Rather than himself defining exactly what tasks would lead to a “100 percent” grade (which could lead students to stop when those requirements are fulfilled), he wanted to encourage those who wanted to learn more to, in Marcus’s words, “just go for it.”

Keeping Learning Conversations Happening

During remote learning, Marcus also found that, because students worked more independently and asynchronously, he had time to have frequent 3–5-minute conversations with students about their learning. A student might read some of their writing, and Marcus could easily give quick feedback, conveying more in a few minutes than if he’d spent a lot of time writing comments. He wondered if he might create a tool that would make it easier to continue these frequent, individual conversations once he had 30 students back in class. Two goals he’s set for his renewed in-person teaching are to have assessment become an ongoing conversation and to give students a chance—even on major assignments—to explain themselves, use feedback, and address mistakes before the final grade.

For a potential solution, Marcus designed a “single-column rubric” to help keep feedback-rich conversations going once students returned to in-school instruction and one-on-one time proved scarce. For each project he assigns, he plans to fill in the single column—labeled “proficient or complete”—with descriptions of what good understanding of key concepts and skills involved with that project looks like. At various points in the project, students will use those criteria to determine if (a) they’re “in the middle” or “proficient,” (b) the understanding reflected in their work seems to fall short of those levels (indicating they’re emerging or developing), or (c) their understanding lands above those levels (extending or sophisticated), and will share their rating with Marcus. Marcus will have a brief talk with each student as time surfaces in the day, and these self-assessments of where each learner is in the process will provide a starting point so he can provide help—or redirection if needed—quickly.

Marcus believes these rubrics will be an important basis for learning conversations and informing assessment. With a classroom full of students, using these single-column rubrics and short chats can help take the place of the longer conversations that happened often during remote learning. Ultimately, he’ll decide the student’s grade for each project. But his assessment process will be informed by student perspectives.

Opening to Change

Big events lead to big changes. We’re just now emerging from one of the most formidable challenges our world has experienced in our lifetimes. I’m humbled by the incredible resilience and hard work I’ve witnessed from all our students and teachers as they clawed through one restriction after the next. Despite the challenges, however—or perhaps because of them—I believe we will see positive changes emerge this fall from the ways we have learned to adapt instructional practices. As educators, we just have to be open to follow our own paths of inquiry.

Related Resource

Read more from Myron Dueck in Giving Students a Say: Smarter Assessment Practices to Empower and Engage.