We just experienced a pandemic. Let that sink in for a moment. Teachers, students, and parents were thrust into digital learning. Ask educators anywhere and they will tell you that the educational output during the pandemic was just not the same as before and the situation resulted in some learning loss. "Learning loss" refers to the general loss of knowledge or skills, often due to a gap or discontinuity in a student's educational experience. Check the achievement data out there, and it appears that teachers are right—there was learning loss during the pandemic (Sparks, 2023). Many attribute that dip to digital learning (Turner, 2022).

Prior empirical studies on digital instruction, on the other hand, tell quite a different story; they suggest that in some cases digital learning can be more effective than traditional, face-to-face modes of instruction. In one meta-analysis, it was determined that students can learn up to five times more material online than in a face-to-face course (Means et al., 2010). Another study, by MIT, showed that digital learning was as effective as in-person courses, regardless of how much knowledge students start with (Colvin et al., 2014). And a more recent study showed that students enrolled in a virtual learning environment prior to the pandemic outperformed students experiencing remote learning for the first time during the pandemic (Beck, 2022). Clearly, this research and many educators' experience over the last few years seem to be at odds with one another.

While the emergency learning conditions during the pandemic took a heavy toll on schools and districts, however, some emerged surprisingly unscathed—at least in terms of student achievement. Recently, I conducted an exploratory study (Drost & Levine, in press), interviewing students, parents, teachers, and administrators in a dozen Midwest school districts about their experiences with digital learning. I wanted to determine why certain districts (with varying demographics) were less impacted by the pandemic than others. When these districts looked at their pre- and post-COVID data (common assessment data, progress-monitoring data, state achievement data, etc.), they did not see learning loss. Their data were primarily equivalent to pre-pandemic levels, but in two of the districts, data were even higher. So, what allowed these districts to be successful in such trying conditions?

Districts that thrived during the pandemic focused learning on pedagogy first and technology integration second.

What I found in my research was that districts that thrived during the pandemic focused learning on pedagogy first and technology integration second. It logically makes sense: these districts capitalized on what teachers were trained to be experts in—pedagogy. I remember saying something similar to myself early one morning in March 2020 as the emails were coming in from my teachers faster than I could handle: we must focus on what we do best—teach!

Four Elements for Success

So, what exactly does this approach look like when using technology to support learning? As I discovered, districts that succeeded during the pandemic engaged in four common practices. While not a perfect recipe for success, these elements below are essential to improving student achievement with technology.

1. Having an instructional framework.

This first element is about ensuring that every teacher knows what an effective lesson looks like in a district. An instructional framework is the way a teacher plans lessons with identified strategies that the teacher and students use to achieve the learning target (Toth, 2022). Instructional frameworks help ensure a guaranteed and viable curriculum (DuFour & Marzano, 2011).

Some of the districts I researched used the 5E model; others used Madeline Hunter's model, Understanding by Design (UBD), or even a homegrown model (or framework that incorporated multiple models based on subject area). Regardless of the framework used, teachers in these districts were clear on what good instruction needed to look like. Each district had an instructional framework solidly in place.

One caveat: Having an instructional framework doesn't mean that we forsake the art of teaching; kids are not machines. They are spontaneous and ever-changing. The best teachers are the ones who creatively deliver instruction within those established frameworks.

The best teachers are the ones who creatively deliver instruction within those established frameworks.

Let's take an example of a teacher who creatively followed an instructional framework using a learning management system. For a unit on the American Revolution, this history teacher used an I Do, We Do, You Do model that allowed for meaningful and deep learning as students described how key battles and individual contributions helped lead to American victory in the Revolutionary War.

The teacher started with an I Do phase where she shared learning objectives, piqued student interest with a video, required students to share prior knowledge, and provided an overview of the content that students were expected to know. Then, in the We Do section, based on a quiz, students self-selected into the two sides of the war, the American or British side. Students then engaged in lively debate based on a reading. Last, students entered a You Do section, where, based on what they had learned, they used their new knowledge to explain legacies of the war that can be found in American society today. That's the instructional framework in action. Now to the creative side: the teacher added learning techniques to engage students. She created student groups based on prior knowledge, provided collaborative space for students to dialogue using a shared page, capitalized on teenagers' desire to debate using a digital discussion board, and incorporated video to hook their interest.

2. Determining a clear pedagogical function.

A second element that was well-defined in the data is identifying and using clear pedagogical functions within each framework. A pedagogical function is best described as the way that a teacher wants students to go about learning the material during a particular part of the lesson. It might be that the teacher wants students to brainstorm or self-reflect or practice. It might be that they want students to discover or explain or self-assess. Because teachers in the districts studied were clear on these pedagogical functions, they were creating explicit instruction, a hallmark of effective instruction (Archer & Hughes, 2011). Explicit instruction is a way to teach in a direct and structured manner. In my experience as a teacher, administrator, and professor, when I lose sight of the pedagogical function because I'm too busy trying to get familiar with technology, my instruction suffers. When I go back to the pedagogy, the learning improves.

Let's return to the American Revolution lesson. In the I Do section, the teacher had two clear pedagogical functions: She drew on prior knowledge and helped students organize their knowledge. In the We Do section, there was a guided support function and a check-for-understanding function. In the You Do part, the teacher assessed to determine what students knew about the topics they studied. By having these clear pedagogical functions, the students were able to understand the ways in which they should go about their learning.

3. Connecting technology to the pedagogical function.

After determining the pedagogical functions, the next step is choosing the tech tools that allow educators to carry them out. When I interviewed teachers and administrators, it was clear that these teachers were letting pedagogy drive the selection of technology tools—not the other way around. For example, instead of saying, "I need to use a Padlet," the statement might be, "I need to find a way to get students to brainstorm their ideas." Once the pedagogical function of brainstorming was established, the choice of which tool to use became clear. The technology simply became the vehicle to get to the pedagogical function.

In my own work with staff during the pandemic, I saw even my best teachers struggling with tech implementation. What was common among those who were thriving, however, was that they identified pedagogical function and then determined technology tools to support that function.

In anecdotally talking with students and more formally talking to some of the parents through the study, I found that putting the pedagogy first seemed to make the switch to remote learning more manageable. Because students knew what the teacher was trying to accomplish, there wasn't as much worry about the technology; the tech flowed more easily. Because the lessons were part of a consistent framework, everyone knew what to do. The technology acted in service of the pedagogy.

Going back to our American Revolution example, the digital tools that were selected were clearly aligned to the pedagogical function. For instance, when the teacher wanted to introduce a new concept while motivating students, she used Edpuzzle, an interactive video tool. When the teacher wanted students to debate, she created discussion boards using a feature in her LMS and engaged in two visible thinking routines: a Tug of War and a What Makes You Say That discussion (referred to as a provocative prompt). When the teacher wanted students to self-assess, she built digital forms with a Google Quiz.

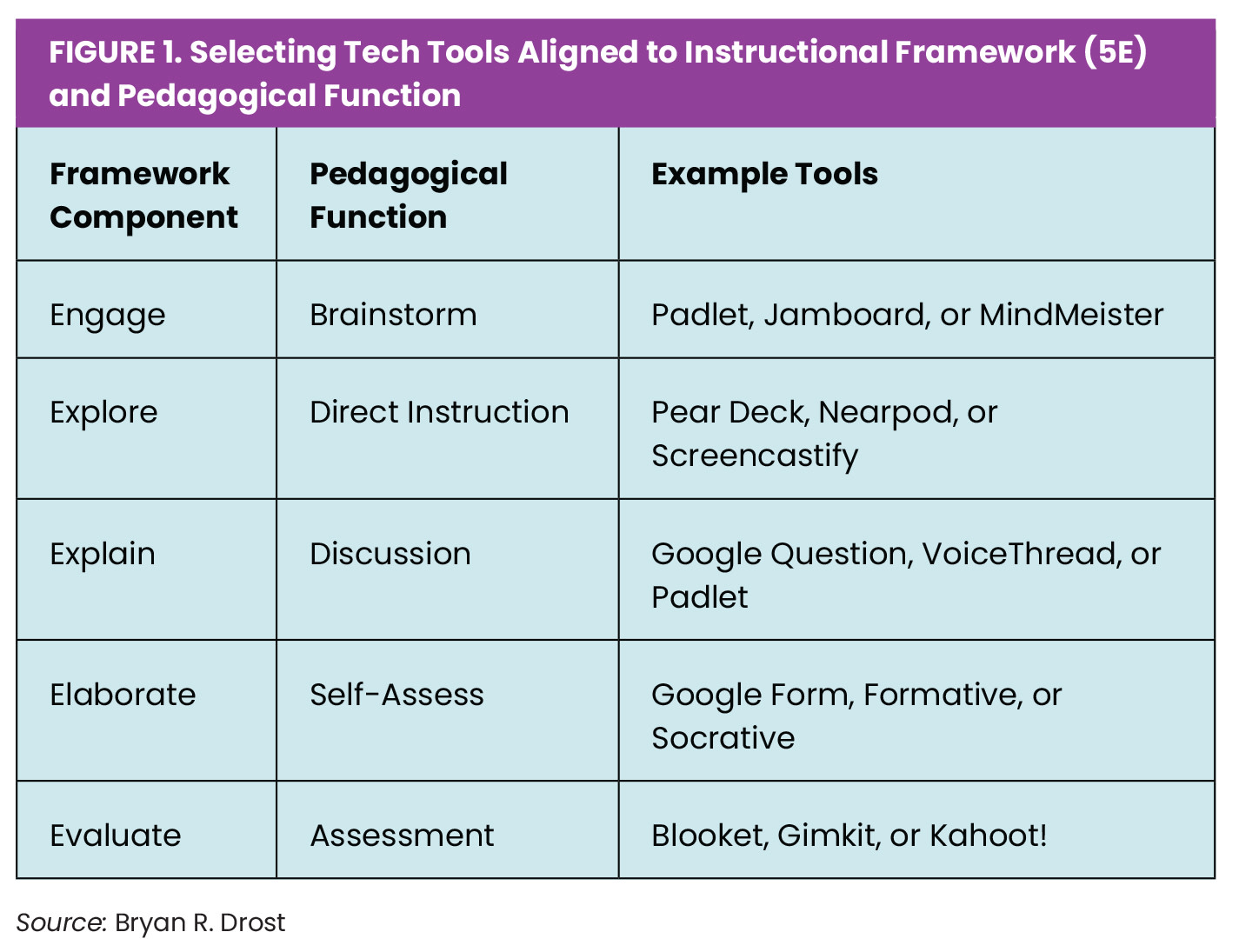

The chart in Figure 1 is a conceptualization of how teachers can connect commonly used tools to a prevalent framework (e.g., the 5E approach). Please note that this chart is not exhaustive, and that some tools can be used for more than one function. (For example, Pear Deck could be used to quickly transfer information to students, as well as to determine what students know about a particular topic.)

4. Capitalizing on the formative assessment cycle.

The last element these successful districts engaged in is taking advantage of the formative assessment cycle. We know that strong formative assessment practices—monitoring student learning and providing feedback and/or making instructional adjustments along the way—make a big difference for all learners. The formative assessment process is a continuous process that includes everything from informal techniques to standardized assessments. What is most important is that the teacher engages in a series of moves (Duckor & Holmberg, 2017) that capitalize on these interactions with students (Drost, 2014).

In talking with teachers and administrators in the study, the use of the formative assessment process came up in almost all conversations. Sometimes this was related to elements one and two as the framework and/or pedagogical function required teachers to think about how they were using student responses to make their instructional adjustments. In other cases, it was related to the fact that nearly everything was getting turned in electronically during the pandemic and there was plenty of work to interpret to determine students' progress toward learning goals and success criteria.

If we return to the American History classroom, you'll see that the teacher planned multiple opportunities to gather information to improve instruction: an Edpuzzle allowed the teacher to figure out what students knew and didn't know; group discussions allowed the teacher to figure out what students were processing; checks for understanding allowed for pivots; and a final activity helped determine what students learned during that lesson. These processes helped the teacher make informed adjustments for future lessons.

Following the Research

Researcher Morgan Polikoff (2021) argues that one of the primary reasons some districts struggled during the pandemic after technology and communication systems were in place was that there was little to no guidance about how to teach K–12 students in a digital environment. In the districts I studied that didn't experience learning loss, these four elements were solidly in place, setting the stage for a smoother transition to digital learning. What these elements show is that educators' focus needs to be on pedagogy, not tech integration. Leaders must ensure that each district, school, and classroom has specific curriculum, instruction, and assessment approaches that allow teachers to make appropriate decisions when they need to use technology.

In my own experience as an educator, I have seen the power that these four elements have in improving student success. While some may argue that we don't need to adhere to them because we hopefully won't need to suddenly switch to digital learning again, I argue differently. By putting these four elements into place in our classrooms now and connecting with appropriate technology tools, our students' abilities to learn at high levels can and should increase exponentially. We will then, most likely, fulfill what the research has said: that digital learning can increase achievement.

Reflect & Discuss

➛ How might adopting a pedagogy-first approach to technology implementation help schools be better prepared for a future crisis?

➛ What criteria are currently in place for determining which technology tools you use in instruction? Do those criteria prioritize pedagogy?