[We pretend] that because yesterday's calendar was good enough for us, it should be good enough for our children—despite major changes in the larger society.—From Prisoners of Time (National Education Commission on Time and Learning, 1994)

The traditional nine-month school calendar long ago lost its reason for being. Harmful to many students, its hold on the majority of U.S. schools is strong, defying obvious reasons for scrapping or modifying it. Designed to foster economic objectives, it has little educational validity.

Yet, today enormous flexibility exists for creating a school calendar that better serves students' educational needs. Most state legislatures require students to attend school fewer than half of the days each year (180 of 365). In fact, if schools alternated in-school and non-school days (ignoring weekends and holidays), students would be out of school every other day!

Perhaps the most important reason for changing to year-long schedules is to eliminate the significant learning loss that occurs during the summer, requiring substantial time each fall for reteaching the previous year's lessons. To those who suggest summer school as a solution, it is well to remember that fewer than half of U.S. students are involved in structured summer learning programs. Further, summer remedial instruction comes too late and generally lacks sufficient focus to be of much help. If Bobby hasn't understood a particular math concept in October, why must he wait until June for the remediation process to begin? Seven months of failure and frustration is hardly an energized prelude to successful summer remediation.

The issue of summer learning loss is a significant one. Do students retain information best by taking a three-month break? If the answer is no, then each school community needs to determine just how long a summer vacation should be. Three weeks or four? Five or six? Certainly not 10 or 12. Encouragingly, more than 2,200 schools, enrolling more than 1,600,000 students, have broken free of the bonds of the non-educational calendar by creating year-round schools (see fig. 1).

Figure 1. Growth of Year-Round Education in the U.S.

Prisoners No More-table

School Year | States | Districts | Schools | Students |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1985–86 | 16 | 63 | 410 | 354,087 |

| 1994–95 | 37 | 436 | 2252 | 1,649,380 |

Source: National Association for Year-Round Education

Why Year-Round Schools?

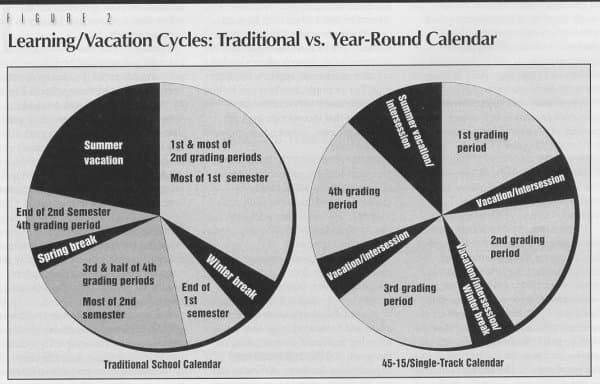

Figure 2. Learning/Vacation Cycles: Traditional vs. Year-Round Calendar

Bringing About Change

- Have a thorough understanding of the benefits of a modified school-year calendar. Those benefits include minimizing summer learning loss; developing a more continuous instructional program to match the way people actually learn; providing follow-up to new learnings with intersession programs; developing a variety of enrichment experiences; and providing remedial classes to correct, soon after they appear, those problem areas blocking academic progress.Reviewing 19 recent studies of academic growth in year-round schools, Winters (1994) found that students in year-round settings performed better on achievement tests than did their counterparts who followed the traditional calendar. The 19 studies yielded 58 categories of academic growth that compared year-round with nine-month programs. Of the 58 categories, 48 (or 83 percent) of the categories were rated plus (+), meaning that in those categories year-round students outperformed their counterparts. Three of the 58 (5 percent) were rated minus (−), while seven (12 percent) were rated mixed results (±).Kneese (1994) also investigated the impact of the year-round calendar on student achievement, matching 311 4th, 5th, and 6th grade students enrolled in year-round classes with students in traditional classes in the same schools. She found statistically significant differences in favor of the year-round students in both math and reading achievement for all students, and especially in reading for at-risk students. Year-round students in low socioeconomic schools also performed better in both reading and math.School districts that follow a year-round calendar have also found better student and teacher attendance, lowered student dropout rates, and decreased antisocial behavior, with fewer discipline referrals and lessened vandalism. Such has been the experience of schools as diverse as Garfield High School in Los Angeles to Robert Coleman Elementary School in Baltimore.

- Allow sufficient time for a school's client groups to understand the rationale for change. Most districts that have modified their calendar have taken from one to two years to complete the task. A few have made the transition in less than a year, and some as long as seven years, but these are exceptions.Client groups include staff, the board of education, parents, students, youth-serving agencies, the business community, and taxpayers. All need to have some understanding of the change and the anticipated results.A common error among those leading the change is to assume that because one group is knowledgeable and accepting, other client groups will be as well. This is not necessarily true. All groups need a thorough understanding of the proposed change, which requires frequent communication.Small-group discussions usually pay higher dividends than large-group discussions. Unfortunately, in the interest of efficiency, many districts hold only large-group meetings, causing unnecessary delays in implementation in the long run. Small-group discussions allow parents, board members, staff, and others to air their concerns. Once their questions are answered satisfactorily, opposition to the change is mitigated.

- Think in terms of a range of options. If a district has several campuses, it can designate some schools as year-round schools and retain others as nine-month schools. Increasingly, parents are requesting choices, and alternate calendars fit the educational tenet that different students learn in different ways and in different time frames.

- Understand that it is impossible to develop one perfect calendar for all. With a growing diversity in family lifestyles and student learning needs, it is imperative that districts provide, to the greatest degree possible within financial and administrative constraints, optional calendars for students' varied learning needs.

A Better Way

If year-round education had been the norm for 100 years, and if someone suggested a new calendar whereby schools would educate students nine months each year, with three months free from organized instruction, would the American public allow, or even consider, such an idea?

The typical school calendar, based on economic rather than instructional considerations, has outlived its usefulness. As Prisoners of Time (1994) suggests, “The six-hour, 180-day school year should be relegated to museums, an exhibit from our education past.” Year-round education offers a better way to educate today's students.