When Jane Maxwell took the helm of Cedar Ridge Middle School as her first principal placement in 2018, everything appeared to be operating well. Test scores at this relatively diverse Virginia school, where 20 percent of students were economically disadvantaged, were strong. Stakeholders seemed happy. A deeper dive into the data, however, revealed that certain aspects of her school were broken for some students. When Jane saw the story of disparate opportunities lying beneath the cover of “averages,” she decided it was time to adapt to bring change. This realization served as the catalyst to decisions that would bring about that change and framed every move Jane and her teachers subsequently made, from de-leveling classes to planning effective professional development.

The scale of change Jane sought to implement was large enough to disrupt the status quo, and it may have backfired on her if she hadn’t consistently kept her teachers’ motivational needs at the forefront of her planning. Jane designed a five-year strategic plan to address her teachers’ needs for purpose, mastery, and autonomy in their learning. (We supported Jane in creating this plan; Mindy and Natalie are lead coaches in her district, and Kristina is a consultant whose work Jane knew of.)

Daniel Pink (2009) describes purpose, mastery, and autonomy as central to people’s motivation in the workplace, and Tomlinson and Murphy (2015) explain their importance in implementing differentiation in schools. Tomlinson and Murphy maintain that if teachers see the purpose of differentiation, feel a sense autonomy in their learning, and sense they are being equipped to master their craft, they’ll persist in the face of challenges. Keeping these three concepts in mind helped Jane adapt her plans to meet challenges that arose before, during, and after the COVID-19 shutdown—while freeing up her teachers to maintain their focus on helping all students grow.

Leading with Purpose

Purpose-driven leaders recognize that the primary goal of school, as Tomlinson and Murphy note, “isn’t gains in student scores but positioning students to be successful individuals in the world” (2015, p. 25). So when Jane and her teachers examined the school’s data to see which students were, for instance, taking early advanced math or world language classes and saw the disparity between students from different socioeconomic backgrounds, and between white students and students of color, they knew had to de-level classrooms. At the time, most Cedar Ridge courses were leveled as standard, advanced, or honors. As a former high school assistant principal, Jane had seen firsthand how middle-school experiences impacted students’ academic trajectories, especially math tracking. As she said in one of our interviews with her:

"If a student got put in a certain level in 6th grade, I could consistently predict where that student would land senior year [in high school]. Scheduling decisions made in 6th grade were limiting kids’ opportunities for the rest of middle school and beyond. . . . That doesn't make any sense to me. Kids grow and change so much during this time of transition, so we have to be as flexible as possible in middle school."

Jane believed her teachers had their students’ best interests at heart, so she had faith that this logic would resonate with her faculty. She trusted them with her thinking and decision making while appealing to their understanding of the pivotal nature of middle school experiences. She and the faculty had conversations about the importance of giving middle school students—who are in the process of trying to figure out who they are—a variety of experiences in many different areas. They agreed on the need to remove barriers to key courses such as math, world language, and popular electives to provide opportunities for most students to enroll, so that when students got to high school, they’d have a more informed idea of what classes they wanted to take and what direction they wanted to go.

Fostering Teacher Competence and Mastery

With teachers on board with the impetus to detrack classes, Jane turned her attention to building teacher capacity to successfully navigate the diversity this restructuring would bring to their classrooms. She knew professional development would need to revolve around differentiated instruction. But she worried that some teachers’ negative associations with the concept would deter their progress. Understanding that each teacher, in their journey toward mastery, had to genuinely believe they could grow in their capacity to differentiate instruction, she looked for a high-leverage opening into the topic. While examining Tomlinson’s 2014 model of differentiation, Jane realized that by focusing on one of its practices—flexible grouping—she could capitalize on the promise of differentiation without conjuring the baggage many of her teachers attached to it.

Flexible grouping is a system of organizing students intentionally and fluidly for different learning experiences within a classroom. In a sense, flexible grouping is the “action step” of sound differentiation, but its success is predicated upon other hallmarks of differentiation such as establishing healthy learning environments and collecting and studying formative assessment data (Doubet, 2022). Jane reasoned that by communicating a clear vision of where she wanted teachers to land, she could “backward map” the requisite skills to get there.

Planning for Mastery

Jane created a comprehensive, cohesive professional development plan that utilized her own professional knowledge, district resources, and outside experts to help teachers feel both challenged and supported. She created grade-level professional learning communities and carved out time during the day for them to meet each week. Teachers’ learning in PLCs was followed by “assignments” asking them to experiment with new strategies and approaches in their classrooms and report the outcomes in their next meeting.

The driving mechanism was getting teachers to try new things, framed solidly by theory but not lost in it. Teachers not only reflected on what they had tried in terms of successes and flops, but also tried to determine why certain attempts had succeeded or fallen flat. Using theory as the “why” and the practice as the “what,” teachers struck a healthy balance as they took risks, asked each other questions, provided suggestions, and reimplemented key strategies.

Modeling Expectations

To support this iterative process, Jane planned faculty meetings as a learning cycle that unfolded over time using this basic structure: 1) Jane modeled a strategy so that it served as a teacher experience; 2) teachers tried the strategy with their students; and 3) teachers brought results of these attempts to PLC meetings and reflected on their progress. As a result, all professional development in the school is learner-centered and illustrative of best practice.

The goal was to equip teachers for mastery, and Jane believed experiential learning was the best way to get them there. "When I do professional learning, I differentiate for teachers,” she explained. "My goal is to model what I expect to see in teachers’ classrooms, so I provide them with a conceptual framework, I give them a task, we reflect on how we did on the task, and I give exit slips. I take those [exit slips] and use them to create the next professional learning experience to address the needs revealed in the assessment.”

This approach means that instances when teachers’ initial attempts aren’t perfectly executed are embraced—because this leads to reflection, conversation, and reiteration. Jane and her teachers realize that some failure and attendant problem solving will solidify teacher learning on both practical and social-emotional levels.

If teachers see the purpose of differentiation, feel a sense autonomy in their learning, and sense they’re being equipped to master their craft, they’ll persist.

Cultivating Teacher Autonomy

When school leaders create conditions for teachers to learn from each other, providing support and guidance in the “just-in-time” manner described here, they’re setting their teachers up to be autonomous learners. Autonomy, perhaps the most important of the three elements of motivation, is the “. . .creative tension between the need to be in control and exercise freedom and, at the same time, the desire to belong to a community of appreciation, support, and cooperation” (Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015, p. 24).

Leaders can cultivate autonomous learning environments by providing a balance of time for planning, support for collaborative analysis, a combination of individual and group processing, and a team approach to strategically assessing progress toward goals (Tomlinson & Murphy, 2015). Let’s consider what’s involved in fostering such learning.

Leading as Coaching

Good coaches—in athletics, the arts, etc.—understand how to cultivate autonomous learning. Jane credits her time as an instructional coach as central to her effectiveness as an instructional leader:

The thing I learned most from instructional coaching was how to ask questions. . . . I am inclined to just tell people how to do things. . .but that’s not going to compel anyone to change their practice! If you sit down and have a conversation with a teacher, you get to the heart of what’s preventing their progress. You can only arrive there by questioning—not by telling.

Strengthening her questioning muscle also helped slow Jane down a bit and listen to teachers more. While she still fights her instinct to rush into action, she has purposefully reframed her thinking, adapting “this is a marathon, not a sprint” as her mantra. Purposefully slowing her pace to run alongside teachers for stretches—rather than always dashing out ahead of them—has made her more responsive to teachers, a much-needed quality during this chaotic year.

Adapting to Change

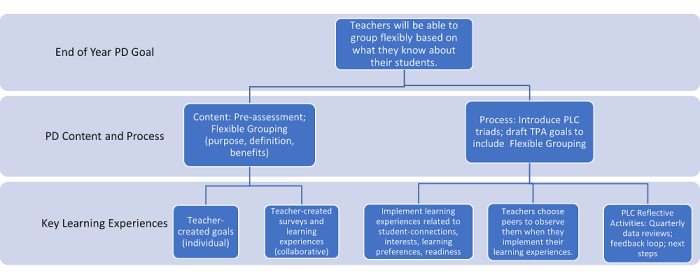

While Jane’s plans for improvement are both systematic and iterative, she leaves space to address evolving needs. Her planning is backwards mapped to learning goals but structured flexibly to allow for pivots as teachers’ learning needs change. Although she plans meticulously, she insists, “I’m not bound by the timeline; I’m bound by the flow.” Figure 1 shows Jane’s structured yet responsive professional development plan.

Figure 1: 2019-2020 Learning Plan

In implementing her PD plan, Jane shifts as necessary to meet the needs of teachers as they strive to meet the needs of their students. For example, when the district moved to online learning in the spring of 2020, Jane maintained her focus on “flexibility” but moved to equipping teachers for flexible instruction rather than flexible grouping, to better meet the needs of faculty and students alike. When some (but not all) students returned to the building in the spring of 2021, Jane reworked the master schedule to ensure faculty members could teach either virtually or in person; she didn’t want anyone forced to do both simultaneously (one of the most difficult aspects of the pandemic for many teachers).

Such flexibility allows Jane to stay the course even in the face of the unexpected. Whether the unexpected is a global pandemic or the more expected shifts in directives coming from the district, she maintains her conceptual framework – her “umbrella”— and finds meaningful ways to make new initiatives work.

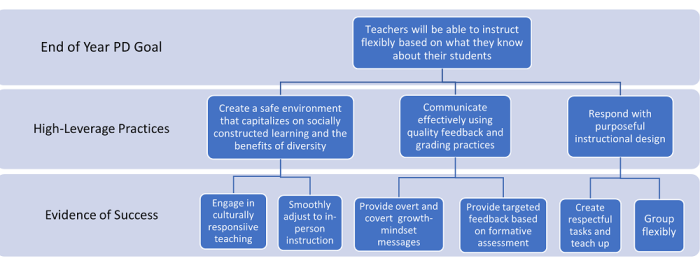

For example, when the district introduced an anti-racist teaching initiative for the 2021-2022 school year, Jane realized she didn’t need to abandon her original professional development plan. Instead, she made culturally responsive teaching (which she views as a part of differentiation) a meaningful aspect of the work teachers were already doing. She expanded her PD conceptual framework to incorporate new components without losing focus on the goals to which faculty had committed. As a result, her original conceptual framework (Figure 1) didn’t shift focus from the goals she and the staff had set; instead, they expanded and became more nuanced (see Figure 2), just as her own understanding of differentiation had become more complex.

Figure 2: 2020-2021 Conceptual PD Framework

Maintaining Collaboration as the Vehicle

Tomlinson and Murphy (2015) assert that “real change is collaborative and should connect practitioners and leaders in focused and supportive work” (p. 24). Jane views collaboration as the vehicle for facilitating authentic growth, believing that if educators aren’t collaborating, only surface-level change to their practice will happen. She applies this principle to her own learning and work with district-level and external coaches:

I have people I collaborate with that help me be reflective, so that I can make really good decisions. Everybody has blind spots. When I collaborate with coaches, it’s a safe place for me to vent and then get down to solving the problem and moving forward.

But Jane considers collaboration with her staff even more important: “I need to make time and space to listen to what they have to say and to openly receive their feedback. If I don’t listen to them, I can go completely down the wrong path — one that feels right to me but isn’t right for my faculty. And then, nothing gets done—well, nothing of importance or impact.” Jane values “sounding boards” who challenge her thinking, then she sits for a while with the ideas these sounding boards share with her. This keeps her thinking malleable and positions her as a learner—two qualities essential for motivating faculty, especially during disruptive times when the temptation is to just put one’s head down and plow ahead.

Keeping Things in Perspective

We believe the kind of work Jane has done to motivate teachers and bring change to her school is replicable by any school leader who is motivated by what’s best for students and teachers, committed to thoughtful planning, and attuned to the needs and insights of their staff. Jane–a teacher-centered principal, just as she was a student-centered teacher–prefers to give the credit to her faculty. “Teachers were ready for the work I brought them. If they weren't already intrinsically motivated, there would have been much more resistance,” she says. And when resistance did arise, Jane operated true to her nature and coaching experience; she had individual, direct conversation with teachers to help resolve concerns and keep them focused.

The Flexibly Grouped Classroom: How to Organize Learning for Equity and Growth

Want to make your instruction more equitable and effective, more interesting, and more fun? Author Kristina Doubet suggests flexible grouping.

By inspiring her faculty with purpose, equipping them for mastery, and providing them with autonomy, Jane Maxwell makes change both attractive and achievable for her teachers. She demonstrates the truth that leadership involves not only promoting change and improvement, but also encouraging and supporting people in their pursuit of a high, even moral, purpose (Brazer, Bauer, & Johnson, 2018).

Note: The principal’s name and the school name in this article are pseudonyms.