We know that stories have a special place in the hearts and minds of learners and have the power to evoke fascination, curiosity, wonderment, and action. Educators often tell stories to enliven instructional content and hook and hold student attention. But what if storytelling could be leveraged to frame an entire course?

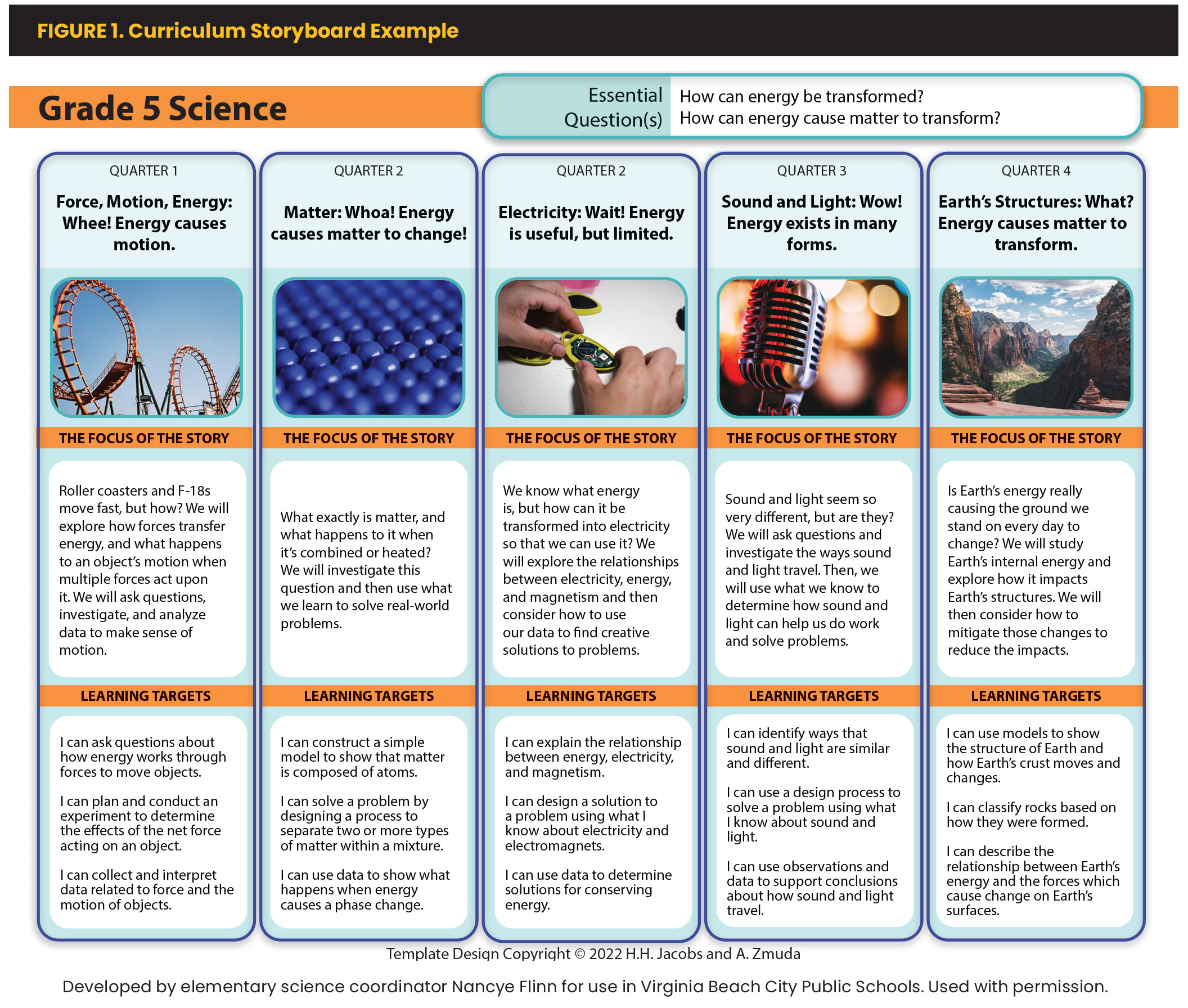

That's the idea behind curriculum storyboards, which share a 30,000-foot view of a given course framed as a narrative or storyline. We've found that this concept has strong appeal in schools. When we share examples of storyboards, such as the one in Figure 1, educators physically lean in to examine further.

The storyboard design in the figure evokes a sense of play, intrigue, and excitement as it showcases a thoughtfully developed narrative about aspects of energy. Recently, when Allison shared this storyboard with some teachers, one exclaimed, "So cool! I want to be in this class." This clear, compelling, and brief design is born out of a deep knowledge of the course content, fluency with external curriculum standards, and commitment to writing in an invitational style to reach the target audience—students and their families.

But "story" is the operative word here. Without a purposeful narrative, a storyboard simply appears as a collection of images aligned to units. Simply using pictures in the planning across a school year doesn't make a story. So what do we mean by narrative, and why does it matter?

Curriculum as Narrative Vs. Curriculum as Coverage

Stories are inherently about connected events, settings, characters, and experiences. Curriculum written as a narrative pulls the learner into the story of a journey through a progression of related concepts. When curriculum is deliberately laid out to invite students and families into the journey across a school year, with visual cues and a writing approach that reinforces throughlines, the impact on the learner is direct. Each student sees that the curriculum "is for me—my teacher is inviting me to join this journey."

The storyboard has long been a powerful tool to help content creators make meaning for a reader or viewer. Storyboards were first formally developed by the Walt Disney Studios during the 1930s by the animator Webb Smith. The impetus was to take the time to ensure the narrative flow and the connection with the audience; studio policy was that audiences wouldn't watch a film unless its story gave them a reason to care about the characters.1 But when it comes to storyboarding, educators have an advantage over movie studios. Filmmakers can only envision a general audience and design broadly, whereas teachers can consider specific students in a specific school setting. The storyboard can be designed in response to the needs of the learners in your care—and can also generate possibilities.

Educators often tell stories to enliven instructional content. What if storytelling could be leveraged to frame an entire course?

The need for a shift in the way we communicate curriculum to parents and students was crystallized for us during the pandemic. When schools shifted to remote learning, they had to send lessons and assignments to students through online platforms. This revealed a problem that existed long before the pandemic: Many educators struggled to make their curriculum clear. If students and their parents don't understand the focus and purpose of a curriculum, then engagement is almost impossible.

When we review district, school, or state curriculum documents, we find that the approach for conveying information on the curriculum is overwhelmingly not invitational; rather, the tone is typically officious and often burdensome. The message is teacher- and system-centric: These are the content, standards, and proficiencies we will cover while you sit in the room with your teacher. Units are often designed in silos rather than with deliberate and transparent connections between previous or subsequent units. If the student cannot describe the connections between units—if they cannot tell the story of a course across the school year—then they are likely to be detached from the learning.

When curriculum designers shift to a more direct, accessible approach, not only do learners gain clarity, they become motivated. To that end, the writing style should be inviting and discursive, with prominent visual cues that encapsulate the essential concepts or big ideas the unit will address.

Helping Teachers Get Started

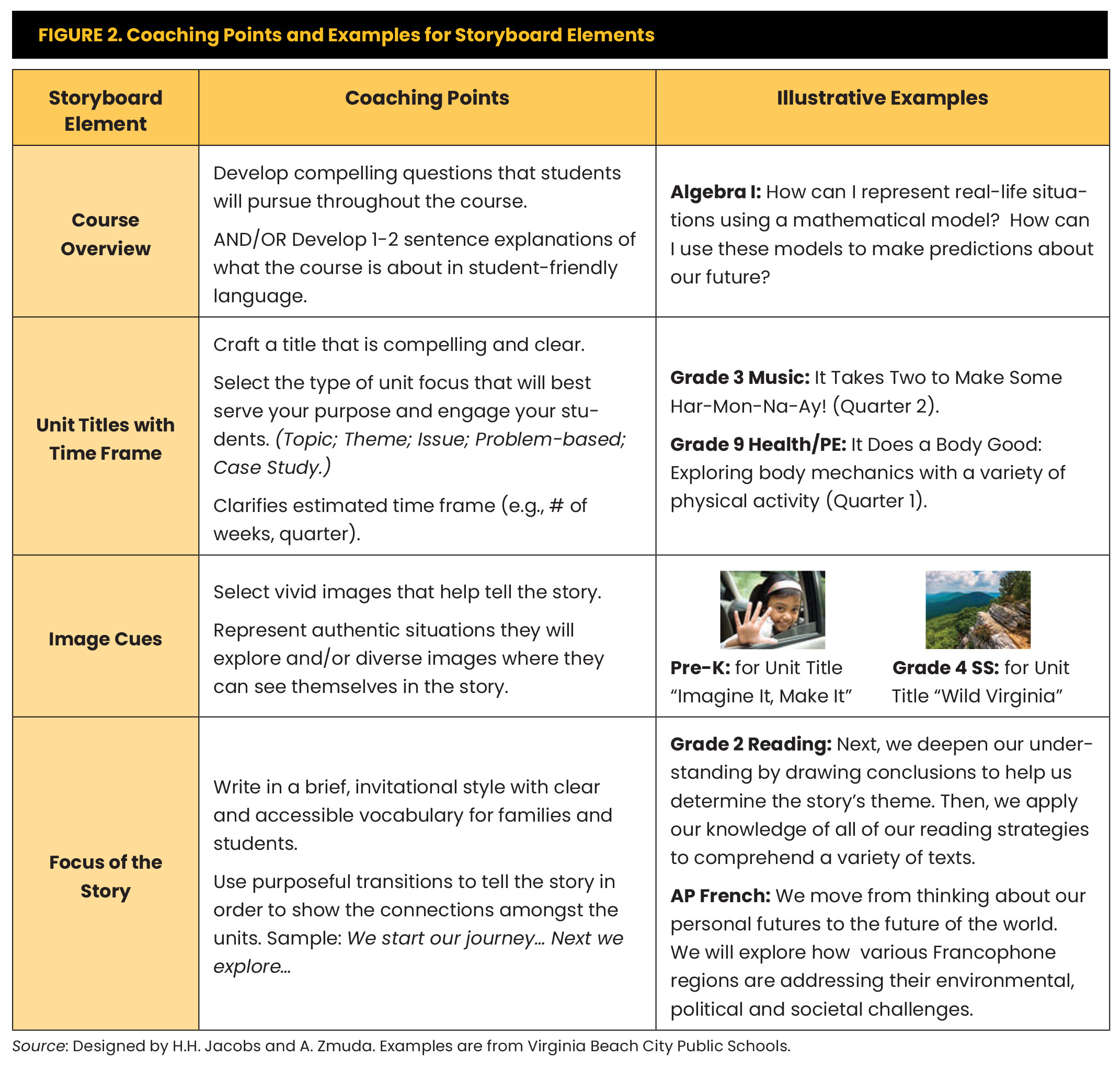

Launching work on curriculum storyboarding typically starts with quickly coaching teachers regarding the key elements of the process and showing stimulating examples from other teachers. Our experience is that teachers "get" the broader concept immediately. To help them gain a more applied understanding, we've identified four foundational elements we believe form the basis of a curriculum storyboard. The table in Figure 2 lists these elements, with coaching points and several illustrative examples for each. (Teachers may also want to review the full curriculum storyboard shown in Figure 1.) Teachers can start drafting these elements in a template, exchanging feedback with colleagues. An important next step is field-testing the storyboard with students and families to get their responses, comments, and questions.

Additional elements can be added to these foundational four. For example, many schools we've worked with have thoughtfully unpacked, bundled, and placed standards aligned to each of the units described on the storyboard. "The storyboard makes the placement and alignment of standards natural for teachers and allows them to see how they are developing proficiencies across the school year," Beth Bartalotta, the principal of Saint Francis of Assisi School in St. Louis, recently told Heidi. Schools or teachers we work with typically start with the overview, title, image cue, and focus of the story and possibly add more elements with time. For example, teachers might add a row in the curriculum storyboard, such as for essential questions, authentic demonstrations of learning, or home resources.

How Storyboarding Helps Teachers and Systems

In our work with schools, we're discovering that teachers and leaders respond enthusiastically to using storyboards for several reasons:

Storyboarding gives students direct access to the curriculum and supports their metacognitive understanding. They see what the curriculum is about—and their role in it.

Teachers report that revising how they present the curriculum makes it more accessible to their students and revives their own personal interest. There is a direct impact on teaching as teachers deliberately emphasize connections, partnering with their students to awaken and discover the ideas across the flow of the school year.

Storyboarding is a useful tool in schools and districts working on curriculum mapping in a software platform. When teachers lay out their storyboard aligned to bundled standards and learning targets first, entering that work into the software program later is easier and less time-consuming.

Storyboarding helps learners make sense of their experiences. Sometimes students add their comments and insights along the curriculum journey directly on the storyboard. In a very real sense, their comments are a source for formative assessment.

Storyboarding is also a visual tool that highlights ongoing school curricular initiatives and goals, such as:

Transfer goals: A storyboard helps articulate how a unit is connected to long-term aims of a subject area (through different grade levels) and the school's portrait or vision of a graduate.

Clear learning targets: The process identifies major learning targets that will be the focus of the story, written in student-friendly language.

Authentic demonstrations of learning: Storyboarding clarifies opportunities for students to apply and demonstrate their learning in authentic ways.

Standards: The process identifies primary standards that are the basis for the learning in each unit, with a hyperlink to the related local, state, or national content framework.

Encouraging student reflections: Storyboards sometimes provide space for students to generate patterns, make predictions, and ask questions on their learning journey through the narrative.

Home Links: Some storyboards identify resources students and families can use to support and extend learning.

Storyboarding resets the creative energy of students and teachers and strengthens families' ability to understand and support their child's learning.

A Source of New Energy

The energy and excitement that storyboarding consistently ignites in teachers has been surprising for us. In responses to storyboard workshop sessions, we frequently hear comments like I see my curriculum in a new light, I'm excited to show this to parents on the opening days of school to clarify our curriculum, The visuals really hook my students' imaginations, or Working through the narrative helps me envision the questions I ask, resources I use, and tasks I develop.

We continue to see new possibilities for storyboarding as a tool students can use to craft their own personalized learning journeys and independent projects. In this time of anxiety and overload, storyboarding can reset the creative energy of both students and teachers, help students engage with the curriculum, and even strengthen families' ability to understand and support their child's learning.

Copyright © 2023 Heidi Hayes Jacobs and Allison Zmuda

Reflect & Discuss

➛ Does this article inspire you to try curriculum storyboards? What benefits do you think it would have in your school or district? What challenges might it present?

➛ Look over some curriculum documents your district or school uses. Does their tone seem, as these authors say, more "Invitational" or more "officious"? In what ways?