Only by the maintenance of high academic standards can the ideal of democratic education be realized—the ideal of offering all children . . . not merely an opportunity to attend school, but the privilege of receiving there the soundest education that is afforded any place in the world (Smith 1971).

What is this "sound education" that the Council for Basic Education, founded in 1956, has been promoting? Is it relevant today, in an increasingly complex, ever-changing world? The call for higher levels of achievement and rigorous academic standards for all students has become a rallying cry for educators, parents, students, teachers, and politicians. A basic education then and today means a liberal arts education that provides the foundation an individual needs to succeed in an increasingly global society.

According to the Council's founders, a basic education has an academic focus, centered on intellectual values. The emphasis on basic education emerged in response to the "life adjustment" movement during the 1950s, a progressive movement that emphasized such nonacademic subjects as health, leisure time activities, and family life. In contrast, the Council emphasized the liberal arts, where all students were expected to study history, mathematics, science, foreign languages, government, English, and geography. The Council considered these generative subjects because they lead students to further learning and understanding in many subjects. What Clifton Fadiman said in 1959 is still astute: "Basic education is... accompanied... by that magnificent pleasure that comes of stretching, rather than tickling, the mind" (p. 8).

This focus on generative subjects enables the individual to develop the capacity for lifelong learning and responsible citizenship. These subjects empower today's students to enter the world of work or post-secondary education.

Today's Basic Education

Basic education today includes the arts, as well as thinking processes and understanding. Students must develop a "capacity for constructive skepticism" and "managing ambiguity"(Barth 1990, p. 2). Students should not only master these basic subjects, but also use constructive criticism. Despite these additions, the Council's definition of a basic education today has not changed dramatically. A focus on a basic education is not a political agenda; belief in studying these subjects does not fall into any ideological category.

Further, basic education as defined by the Council is not the same as the back-to-basics movement that emerged in the 1970s, emphasizing a return to teaching the fundamentals of reading, writing, and arithmetic. Back-to-basics is a more constrictive philosophy, emphasizing the learning of skills, rather than developing understanding. It is often typified by rote memorization and multiple-choice tests, rather than a true mastery of subject matter.

Basic Education and Standards

The need for a basic education has never been as important as it is today. All students need the advantage of a liberal arts education, whether or not they are college bound. Nowadays, people may have several different jobs with several different employers in the course of their careers. These jobs demand mastery of a diverse range of knowledge and skills that people must be capable of mastering either through additional education or job training. Higher standards in schools will prepare students to meet the demands of a changing workplace.

A 1997 Massachusetts English language arts standard expects students to "write coherent compositions with a clear focus and adequate detail, and explain the strategies they used to generate and organize their ideas."

A 1996 Los Angeles history standard expects students to "analyze the historical interdependence of United States and world cultures."

A 1995 Delaware mathematics standard expects students to "solve quadratic equations with real roots using a variety of algebraic and graphical methods and tools."

When academic standards are linked to the liberal arts, they help ensure that students are mastering basic subjects.

Standards and the Workplace

Today's workers need higher and higher levels of skills. In a U.S. Census Bureau survey, "fifty-seven percent of the employers said the skill requirements of their workplaces had increased in the last three years" (Applebome 1995). Factory workers no longer can get by with a minimal level of education; employers expect them to solve complex problems and interpret lengthy service manuals. For example, companies like Corning, Motorola, and Xerox need educated workers, because they "replaced rote assembly-line work with an industrial vision that requires skilled and nimble workers to think while they work" (Baker and Armstrong 1996).

This notion of having to actually think while on the job was unheard of decades ago. Automobile workers are now being tested in mathematics, science, and manual dexterity. As technology advances, manufacturing industries expect workers who are "literate, numerate, adaptable, and trainable—in a word, educated" ("Education and the Wealth of Nations" 1997). And thousands of prospective workers find themselves lining up for factory jobs and being turned down (Narisetti 1995) because they lack the advanced skills required in the manufacturing sector.

We can resolve this disconnect between worker skills and the realities of the workplace. If students graduate from schools that have high academic expectations, companies will have internationally competitive work forces. Schools that have low expectations will not prepare students for today's jobs. Rigorous standards grounded in the liberal arts are the key to guaranteeing that students graduate with a sound basic education that prepares them to enter the world of work and life.

Standards and Equity

A solid basic education can also address educational equity. We are bombarded with statistics about the widespread student underachievement in mastering academic basics, particularly in urban districts. Recent studies indicate that students in high-poverty schools perform at lower levels than students in low-poverty schools, and that achievement falls still further when high-poverty schools are located in urban areas (NCES 1996).

One tool to remedy this inequity is to raise student achievement by implementing challenging academic standards that all students have the opportunity to meet. By creating rigorous standards and holding high expectations for all students, we can address the equity dilemma. As David Hornbeck (1992, p. 32) notes:The single greatest obstacle faced by poor and minority students is the low expectations most adults have for their performance. Expectations are powerful, self-fulfilling prophecies. A highly visible national process of creating high standards and a rigorous examination system would create expectations for disadvantaged students that are not lower than those held for others.

Academic standards in many states not only address the importance of certain skills and knowledge, but also address the equity issue. As citizens in a democratic society, we owe it to our children to offer the same opportunities and expectations to learn and succeed, no matter where they live or go to school. Academic standards are a step in that direction.

Standards and Teacher Qualifications

The emphasis on standards and basic education sounds good on paper, but the key is whether the rhetoric can be translated into classroom practice. If our goal is for all students to meet the standards, then teachers are the means. "Teachers, too, will be expected to know not only what the standards require but also how to enable students to meet them" (Stoel 1997). But many teachers are not as qualified as they should be to teach the subjects they teach.

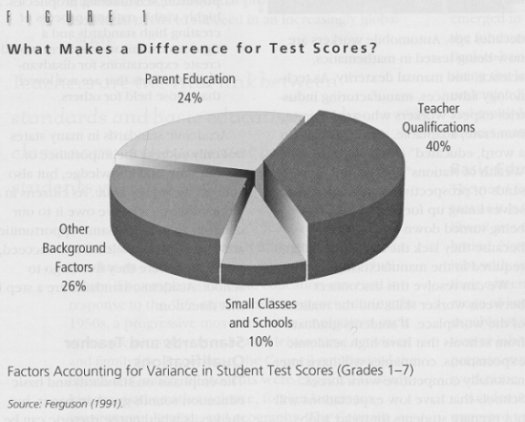

According to a U.S. Department of Education survey, the percentage of teachers with a state license and a major in their primary teaching assignment field ranges down from 83 percent for pre-K to elementary teachers to 52.6 for mathematics teachers (McMillen et al. 1994). These percentages, particularly for math and science, are unacceptable. In addition, in one study, student test scores varied by 40 percent as a result of teacher qualifications (fig. 1) (Ferguson 1991). Such data demonstrate that too many teachers lack the knowledge and skills they need to raise student achievement and help students meet the new standards. When almost 25 percent of all secondary teachers and 30 percent of mathematics teachers do not have a college minor in their teaching assignment field, something is wrong (National Commission on Teaching and America's Future 1996). How can we expect students to reach higher standards if teachers do not have the proper qualifications for teaching in their assigned field? Teachers are the vital link between standards and basic education in the classroom; if they are not prepared, their students will not be prepared.

Figure 1. What Makes a Difference for Test Scores?

Groups such as the Council for Basic Education have advocated for higher academic standards for decades. Standards provide focus, direction, and the basis for accountability. They challenge all students to acquire the knowledge and skills necessary to be successful today. Both students and schools must be held accountable if standards are to be effective. It can no longer be assumed that students will graduate with an education that prepares them to be successful and responsible citizens.