Two boys are brought to the office after almost coming to blows in the hall. The teacher who found them reported: "They were yelling expletives at each other and were very close to a fight, so I had them come here for you to decide what to do."

As the assistant principal, I asked the teacher to record the situation on a referral form. One student waited in my office; the other sat in the conference room until they both calmed down. As the teacher wrote the report, I asked her if any students saw the incident. She said that there were many witnesses, but they scattered when she arrived.

Not surprisingly, fighting, shoving, grabbing, verbal insults, and threats are major problems in schools. Students often report that such incidents occur in hidden areas, such as bathrooms, locker rooms, and halls, where teachers are less likely to appear.

In the last few years, schools have made innovative attempts to decrease violent conflicts through conflict resolution classes, peer mediation, and staff development programs. Such efforts, however, get mixed reviews by students, teachers, and law enforcement officials, since not every school has them, and few K–12 curriculums address violence prevention.

Wall Wonders

East Lyme High School in East Lyme, Connecticut, is a comprehensive public school with 1,050 students—almost all white, middle-class—in grades 9-12. Two years ago, we began offering a credit course in conflict resolution, cotaught by a life skills teacher and a special education teacher. As the supervising administrator, I helped develop the curriculum, which includes staff development activities, such as attending workshops, visiting other schools, and gathering curriculum materials.

After observing students in these classes, I thought it would be helpful to create another format for conflict resolution. I developed a systematic approach that could be used by teachers and administrators. My office wall became the backdrop for a series of large posters representing model conflict resolution practices. Following is a narrative showing how the two boys described earlier participated in the process.

First, we established some basic facts in the incident—not easy, since both boys had difficulty remembering. Between their fragmented stories and common sense, however, we got an idea of what took place. When both students were calm enough to sit together, we established a rule that only one person could speak at a time. Our goal: to obtain an accurate account.

- Step One: I read the first poster to the students, defining conflict as "an expressed struggle between at least two people who are interfering with each other in achieving goals."

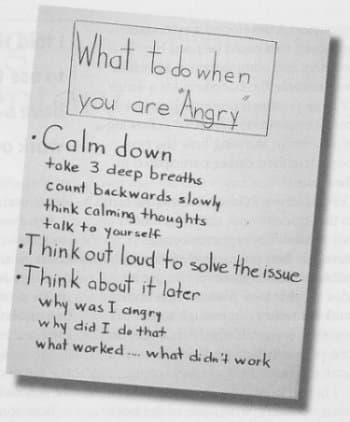

- Step Two: I read the second poster, "What to Do When You Are Angry," which includes tips such as taking three deep breaths and counting backwards slowly. At this stage, I made sure that the students were calm enough to begin resolving the issue. In other situations, students had sometimes expressed (or it became evident) that they weren't ready, so we waited.

- Step Three: We discussed the meaning of win-win and the process of reaching it. The students began sentences with "I feel . . ." and completed them with their thoughts. At first, the boys had difficulty coming up with a word, so I offered suggestions, including insulted, frustrated, intimidated, and impatient.

- Step Four: At this critical stage, the students saw a cause-and-effect relationship, and determined what actions they may have taken to escalate the situation (such as issuing put-downs, threats, dirty looks), as well as what solutions might be used to de-escalate it, like walking away and cooling off. For the two boys, the poster became the key to resolving the issue.Both students located their feelings on the "Conflict Escalator." I responded that if we had reached the explosive step (actual fighting), I would have called the police and they might have been charged with disorderly conduct or even assault. "Let's see what methods can be used to get back down to the 'calm' step on the escalator," I said. "You both need to remember that it takes longer to move down the escalator than up." The boys used the strategies, admitted their part, and apologized to each other.

- Step Five: The boys reviewed the poster, "Active Listening and Roadblocks to Communication," which included techniques for encouraging students to speak ("Tell me more about . . .") and possible roadblocks, such as ordering or giving commands ("You must . . ."). This step is used if needed.Posters are color-coded to help students visually process these steps; students add information as they come up with other insights and suggestions. In this way, the wall is a work in progress that reflects each situation as dynamic and changing, bringing individual nuances that require separate solutions.

What to Do When You Are Angry

Final Reflections

The Conflict Wall has quickly become a routine part of the school culture, and students, teachers, and parents often use it successfully. Wall interactions have become opportunities for students to provide their own solutions through constructive problem solving.

A traditional approach to the boys' confrontation might have been for each boy to state what happened and then have their stories verified by witnesses. After hearing each account, the administrator would tell each student what the other said and arrive at some agreement. At individual conferences, we would see how each boy contributed to the problem and what part each was responsible for. Resolution would be through disciplinary action, including suspension and a parent conference before students could return to school. This method results in less effective solutions. Students are more likely to commit to positive resolution when they are in control of the outcome.

Before we began using the wall, quarreling students usually sat in my office with downcast eyes, an immediate barrier to first attempts at resolution. The wall forces students to look up and begin to intellectualize the situation. Their emotions, while still important, have a secondary place as the students work through the steps. Often they reach solutions that may not require disciplinary action.

Everyone who comes to my office sees the Conflict Wall, and we discuss the process at freshman orientation. In addition, three neighboring school systems now offer the conflict resolution class. The peer mediation program also ties in with the conflict resolution course and the wall content. In a short time, these critical components have effectively produced a school environment that fosters appropriate assertiveness, problem solving, and communications skills, as well as ways to control anger. We have woven conflict resolution skills and procedures into the fabric of school life.