Consider two freshmen—Bryant, who is starting high school, and Jillian, who is in her first semester at a university.

Despite their age differences and the fact that they attend schools on opposite ends of the country, these two students have a lot in common. They are conscientious. They attend classes regularly. They dutifully do their work. As a result, each enters their new schools having earned a , B, average—which should signal they are adequately prepared to perform at the next level. But this is where the story takes a turn, because, unfortunately, Bryant and Jillian share something else in common: They find themselves woefully unprepared for the demands of their new English classrooms.

What do we mean when we say they are unprepared? Take writing, for example. In their previous schools, Bryant and Jillian were "one draft and done" writers. They could get away with putting forth minimal effort because they were repeatedly given the same kind of writing assignments—most often literary analysis essays—and they dutifully completed them. Writing became a mechanical task where the "shape" of the essays was determined by the teacher. Heavily aided by SparkNotes, they wrote to please their teachers, but in doing so, they didn't think very hard.

Bryant and Jillian now find themselves in classes where they are asked to write narratives, informational texts, arguments, digital compositions, and multi-genre papers without being given any templates to organize their research and writing. They are willing, and they want to succeed—but they don't know how to generate and organize their own thinking. Instead, they spend much of their time trying to figure out what the teacher wants them to say, and , how, the teacher wants them to say it.

When students haven't been required to wrestle with difficult writing decisions—and when much of that decision making has been done by the teacher—they lose their sense of agency and their confidence as writers. Bryant and Jillian have ended up frustrated because they've had years of the same kind of writing practice. Their good grades in previous classes represent acts of compliance, not decision making. Suddenly, they have their first understanding of just how unprepared they are.

Jillian, for example, is currently writing about climate change for her freshman seminar course on "Tackling a Wicked Problem." Her professor hasn't given her a template or rubric. He just asked her to research a problem and present a recommended course of action, so she has a lot of decisions to make: What order of information will be most effective? Should she begin with an anecdote? If so, how will that set the tone for the piece? How can she most effectively weave together her anecdote and evidence to keep her readers engaged? How should she focus the piece in order to communicate the urgency of this issue? What are the anticipated counterarguments, and how will she refute them? Jillian finds herself in panic mode—not because she's lazy or uninterested—but because she doesn't believe she can do it. She doesn't know where to start.

Jillian's former teachers had good intentions. They created templates and step-by-step tasks for students because they had watched young writers struggle or give up entirely, and they wanted to help. Like many teachers, they might have concluded that students , can't, write well without detailed teacher's instructions.

We disagree with that assumption. We believe struggle is necessary in building the capacity to make decisions. We are reminded of Ellin Keene's research on engagement. Keene and her colleague Matt Glover (2015) challenge teachers to consider the consequences of their overprotective practices: "You may find yourself wondering why you've felt the need to break down tasks into an infinite series of first steps that somehow never add up to the authentic learning experience you'd hoped to create" (p. 108). Completing teacher-generated step-by-step work is not learning; it masquerades as learning.

Teachers who make decisions on organization and development for student writers are usually unaware of the damaging impact this can have. But as Peter Johnston (2004) notes, "Being told explicitly what to do and how to do it—over and over again—provides the foundation for a different set of feelings about what you can and can't do. … The interpretation might be that you are the kind of person who cannot figure things out for yourself" (p. 9). Which brings us back to Bryant and Jillian—and many other students we have encountered—who've come to the next step in their education ill-equipped to figure things out on their own.

We want our young writers to make their own decisions, but we know that we need to teach them the habits of mind they will need to draw upon to do this. Such habits are sharpened through repeated wrestling matches with drafts—and through seeing seasoned writers actually work through numerous drafts.

We believe it's essential to model the writing struggle. In our secondary English language arts classrooms, we each model in front of our students our thinking about something we're currently composing. We occasionally show students a draft, asking them to tell us if it achieves what we intended. As we talk about our choices and compose in front of our students, we reveal our decision making before drafting, while drafting, and in revising.

When Penny shared with students an early draft of a piece of writing about her father, for example, she asked them to consider the mix of dark and joyful moments in the piece. She worried the balance was off, she told students, and wanted to know what they perceived in the piece. In this way, she invited students to join her in the decision-making process. When students see their teachers wrestle with writing, it fuels their own desire to write, their determination to figure out a compelling organization, and their willingness to re-read, revise, and shape their writing for an intended audience. They come to recognize that wrestling with decisions is what writers do. It's , normal,.

Taking ownership of the hard decisions required to craft a compelling piece of writing is empowering. It's also critical that students realize they may not know exactly what they're going to say or even focus on until they start writing. As Peter Elbow states, writers often find themselves starting "with incomplete pieces of feeling, impulse, meaning, and intention—and gradually building them into completed texts; letting the process of writing itself lead them to ideas and structures they hadn't planned at the start" (2000, p. 363).

We lead students to try this exploratory process by having them do daily, ungraded, low-stakes writing in notebooks. We use poetry, photographs, or infographics to inspire student thinking. We don't give them prompts. In these notebook entries, students choose a word, line, or passage that inspires 10 minutes of writing prose or poetry, then reread what they've written and work to improve it. We often close with students sharing a favorite line they've written, which demonstrates the wide range of thinking and writing in the room.

Such free, expressive writing leads students to confidence, fluency, and agency. We also spend time convincing our students that their ideas—as fragmented and unorganized as they may be—can be developed into powerful pieces of writing. To help them realize this, we study mentor texts, paying close attention to how authors develop their ideas. For each genre we consider in class, we study multiple authors—and thus multiple approaches to writing—and we ask our students to carefully consider the decisions behind the creation of these pieces.

Students extend this study of the writing process by meeting in writing groups with their drafts in hand. In groups of four or five, they practice listening to a writer's intentions and then reading the work to see if it matches those intentions, as well as getting responses to their own pieces of writing.

We select these groups, carefully considering the placement of writers who may need nurturing. Once grouped, students respond to each other's papers in person (in class), as well as digitally (outside of class). We use Flipgrid to create this digital connection, where our young writers—via video postings—ask their peers for targeted responses to their papers. We've found that the distance created by this technology actually brings our writers closer together: Students often give more honest, valuable feedback when they aren't physically sitting next to the writer.

This is not a peer-editing exercise; it's about generating meaningful peer , response,. One teacher's response is too limited to provide the richness of feedback that our young writers may need. When they hear from other writers as well, they are better positioned to evaluate their own work, to understand where their writing communicates their intentions and where it doesn't.

We recall the words of Donald Murray (1982), who defined a writer's inner dialogue:

The act of writing might be described as a conversation between two workmen muttering to each other at the workbench. The self speaks, the other self listens and responds. The self proposes, the other self considers. The self makes, the other self evaluates. (p. 140)

We believe peer response jump starts this kind of important inner dialogue. We hope feedback from other writers helps students to adopt the habit of muttering to themselves as they compose.

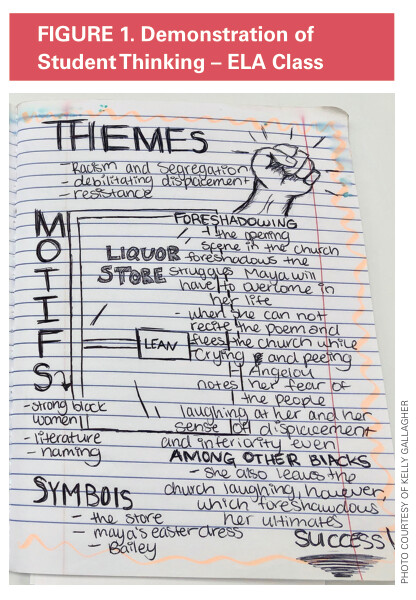

Empowering students to make their own writing decisions extends beyond essay writing. When students read books, for example, teachers often want them to explore their thinking via more informal writing. But with our students, we don't do formative assessment of their reading progress by asking teacher-generated questions. If our students begin by answering , our, questions, we may be guilty of determining from the outset what their thinking will (and won't) be. Instead, we ask students to read large chunks of text—60 or 70 pages—and then demonstrate their own thinking about the text through informal writing and drawing. They share this thinking via two-page spreads in their notebooks (see Figure 1 for an example). Notice that student-generated thinking comes in all shapes and sizes—and doesn't always fit neatly into the "boxes" of teacher-generated questions.

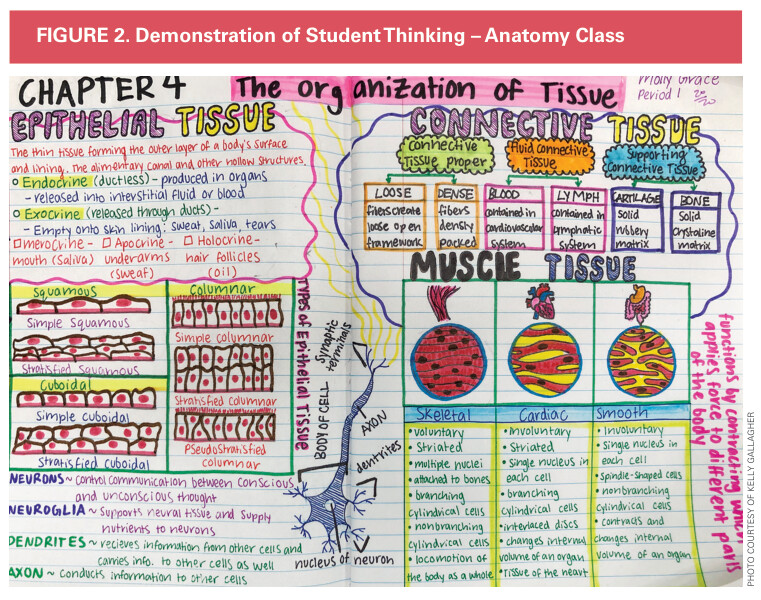

This is not just a strategy for English classes. A colleague of ours, Susan Fried, has her students generate two-page spreads demonstrating their thinking in her human anatomy classes (see Figure 2 for one of her student's demonstrations of thinking created after reading a chapter on the structure of tissue).

We aren't suggesting that teachers stop asking questions. We still ask our students questions. But we don't , begin, by asking questions. We begin by having them wrestle with their thinking. We know many of them will have trouble with this approach, since they have found comfort in dutifully responding to the teacher's questions and many have reached a place where they like being told what to take from a text. But we also know that encouraging them to begin generating their own thinking is an essential step in empowering them.

Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt, authors of , The Coddling of the American Mind, (2018), argue that many students who reach college today have suffered from growing up in a culture of "safetyism." They are unprepared for the rigors of college because their parents adopted a misguided mindset that children are fragile and have gone out of their way to make sure their children don't encounter too much discomfort. This is ironic because the attempt to protect their children from difficulties has actually led to these students being less prepared to face the rigors of college life. It turns out that "helicopter parenting" is counterproductive to building independent, confident, and creative children.

We believe "helicopter teaching" is also counterproductive to building independent, confident, and creative students. Too often, in trying to help students, teachers do too much of the thinking. Students come to rely on formula and standardization—and when formula and standardization take hold, the energy and intellectual rigor that comes from creation gets lost. Students become disengaged. Most important, they get away with this disengagement because they've figured out a way to settle into comfort zones where hard thinking can be avoided. When this happens, students run the risk of ending up like Bryant and Jillian, owners of good grades who find themselves overwhelmed in their new classes.

As Lukianoff and Haidt remind us, our job is not to prepare the road for the child; our job is to prepare the child for the road. We believe that preparing children for the road begins by creating classrooms where the teacher cedes much of the decision making to the students.

Gallagher Reflect & Discuss

➛ How might you "model the writing struggle" for your student writers? How could you model productive struggle in another discipline?

➛ Do you ever slip into "helicopter teaching" when a student is having a hard time academically? How can you avoid this tendency?