Driving instruction with high-stakes tests will not improve schools. A large body of research demonstrates that high-stakes testing narrows curriculum and dumbs down instruction. It causes students to turn off, tune out, and often drop out; induces schools to push students out; increases grade retention; propels teachers to leave; and inhibits needed improvements. In the end, high-stakes testing will hurt students—particularly those students who most desperately need better schools.

A Poor Record

States that did not have high-stakes graduation exams were more likely to improve average scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP) than were states that did have such exams (Neill & Gaylor, 2001). At the same time, NAEP score gaps between low- and high-income students did not narrow (Barton, 2002).

States without graduation tests were more likely than states with such exams to show improvement or to improve at a faster rate on a variety of tests, including the NAEP, the SAT, and the ACT (Amrein & Berliner, 2002).

Data from the National Educational Longitudinal Study indicated that high-stakes testing was not associated with improved scores but was associated with higher dropout rates (Jacob, 2001).

These reports and many others show that the focus on tests has not produced the promised results. Claims of improvement typically rest on inflated scores on state exams. Texas, the model for the new Elementary and Secondary Education Act, provides a good example. As Texas Assessment of Academic Skills scores rose dramatically, the state's NAEP reading results did not change significantly. At the same time, the racial score gap in Texas widened (Neill & Gaylor, 2001). Meanwhile, the test-driven approach in Texas led to a much higher dropout rate, particularly for Latinos and African Americans (Haney, 2000, 2001).

An Equally Poor Outlook

If high-stakes tests have not led to improvement by now, will they ever? Two important factors suggest that even if they could in theory, they won't in practice.

Socioeconomic effects. Low-income and African American and Latino students enter school substantially less prepared to do academic work than their middle-income (never mind wealthy) or white or Asian peers (Lee & Burkam, 2002). In addition, the first group attends schools that are far less prepared, in terms of teachers and physical resources, to teach them. Rothstein (2002) points out the vast disparities in housing, health care, and other supports available to children. Those who start with less get less, and as a result they either fail to catch up or fall even further behind. Without major social investments in both classroom and out-of-school supports for low-income children, it is absurd to believe that more tests will enable schools to overcome the gaps in academic learning.

Several reports over the past few years have purported to show that large numbers of schools serving low-income students have succeeded in overcoming the effects of poverty. More careful studies, however, have shown these claims to be at best wildly inflated and often completely misleading (Krashen, 2002). Simply demanding higher scores, even with rewards and sanctions attached, will not do the job.

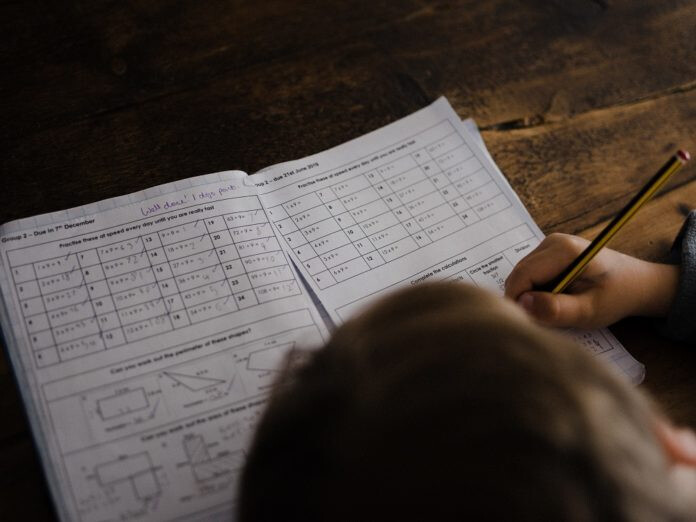

Teaching to the test. Any exam can only sample the curriculum that students should learn. For test results to be valid measures of real learning, students must have been taught a full curriculum. If instruction narrows to focus on the limited sample covered by the test, scores become inflated and misleading. This largely explains the difference between results on state-specific tests and those on such neutral measures as the NAEP.

Many supporters of test-driven “reform” argue that it will at least guarantee that teachers teach the basics (which the test will supposedly cover), and will thereby initiate a positive reform process. Unfortunately, test-driven schooling often fails to provide even the basics. For example, some reading teachers teach students to “read” by looking over the answer options to questions attached to short reading passages and then searching the passage to find a clue for selecting the answer. Others drill phonics, but never get to comprehension. As a result, independent evaluators find that the students cannot explain what they have just read—meaning they actually cannot read (McNeil & Valenzuela, 2001).

A Flawed Concept

Testing proponents believe that focusing on a limited set of skills and facts will prepare students for further education—a theory based on profound misunderstandings of how humans learn. Shepard (2000) has demonstrated the mismatch between tests and learning, a point also developed in rich detail in several books from the National Academy of Sciences (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Pellegrino, Chudowsky, & Glaser, 2001). In short, humans learn best through active thinking. “Learning” while not thinking is like remembering lists of phone numbers one will never call. Memorization of facts and procedures has its place, but deep learning must engage the brain and spur thinking. Teaching to the test rarely accomplishes either.

Overall, state tests do not do a good job of measuring state standards, particularly higher-level thinking. Researchers at the University of Wisconsin found that state exams poorly matched state standards and measured mostly lower-level thinking (Wisconsin Center for Educational Research, 1999).

In a high-quality education, students conduct science experiments, solve real-world math problems, write research papers, read and analyze books, make oral presentations, evaluate and synthesize information from a variety of fields, and apply their learning to new and ill-defined situations. This work provides them with both deeper substantive knowledge and higher-level thinking skills. Standardized paper-and-pencil tests are poor tools for evaluating these important kinds of learning. If instruction focuses on the test, students will not learn the skills that they need for success in college and beyond.

What's the Alternative?

If focusing instruction on large-scale, high-stakes tests will not lead to genuine improvements in our nation's schools, what should schools do in response to high-stakes testing mandates?

Educators can take some comfort from the knowledge that employing richer curriculum and instruction is likely to somewhat improve standardized test scores (Center for Collaborative Education, 2001; Institute for Education and Social Policy, 2001). In Chicago, students of teachers who used more interactive rather than exclusively didactic instructional approaches gained more than their peers on the Iowa Tests of Basic Skills (Newmann, Bryk, & Nagaoka, 2001; Smith, Lee, & Newmann, 2001).

One can also assess higher-level attributes. Teachers do it all the time. Studies of a group of small schools in New York City and similar schools in Boston described these successful schools as having high standards and rigorous assessments (Center for Collaborative Education, 2001; Institute for Education and Social Policy, 2001). The high schools often require students to present and defend their work in a number of subject areas to earn a diploma. A committee that typically includes outside experts reviews the work. As Meier (2002) says, these high standards do not entail the standardization or drill-and-kill imposed through high-stakes exams.

These high-quality schools in New York and Boston generally do not focus on teaching to the test; indeed, many are struggling to avoid being coerced into becoming test-prep programs. They demonstrate their success by far more than test scores. Deborah Meier's Central Park East Secondary School, for example, prepares low-income students not only to enroll in college but also to succeed there—a far more important goal than merely increasing their test scores (Meier, 1995). Indeed, Meier has often pointed out that although her students learned to succeed, their standardized test scores did not necessarily show substantial gains. These schools succeed not by teaching to standardized tests but by teaching for deeper, important learning.

Some have argued that such schools cannot be replicated. They presume that test-driven improvements can be. However, researchers from the Dana Center went hunting for successful Texas school districts that had improved scores and closed racial score gaps (Skrla, Scheurich, & Johnson, 2000). Using modest criteria that were overly dependent on TAAS scores—enrollment of 5,000 or more students; high poverty levels; and 50 percent of the high- poverty schools in the district categorized as Recognized or Exemplary on the basis of their state test scores—they studied data from all Texas districts. They found only 11 districts to examine closely, which they reduced in the end to 4 successful districts. In other words, after nearly a decade in which the state had focused on high-stakes testing, sympathetic researchers found only a few districts in the state to meet their narrow criteria for success.

Unlike high-stakes testing, which undermines good schools and prevents real improvement, better forms of assessment can play a powerful role in improving schools. Most important is assessment that provides meaningful, usable feedback to students and engages them in self-evaluation. A research summary of more than 250 articles and chapters by Black and Wiliam (1998) found that formative assessment can contribute more to improving outcomes (primarily as measured by test scores) than any other school-based factor, benefiting low achievers more than high achievers. In other words, formative assessment helps raise everyone's achievement while also closing the gaps—which test-driven reform has not done. This approach, however, requires treating teachers as professionals, improving professional development, and spending more money.

Rather than chasing the illusion that test-driven change will produce significantly improved learning, policymakers need to shift attention to practices and models that emphasize serious thinking and skilled teaching. If we do less, we consign far too many students to a continued second-class education. At the moment, few policymakers recognize this. It appears that to get on the path of genuine improvement, educators and parents will have to join together to beat back test-based “reform.”