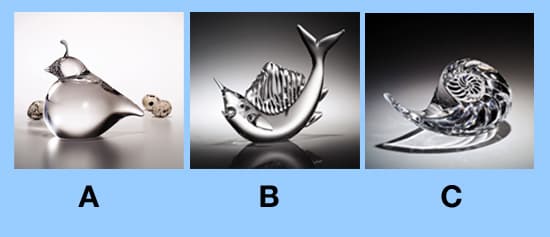

Let's start with a simple assessment of your ability to evaluate some pieces of art. Below, you'll find photographs of three pieces of Steuben glass. Steuben has been designing luxury handcrafted crystal since 1903. Your task is to rank the three pieces in order of increasing market value.

Figure

Write down your value rankings before you check the answers at the end of this article.

How well did you do? Was the task difficult? If so, perhaps it's because you had limited information about each piece. You were not given any dimensions—one piece could be much larger than the other two—and you were only given one view of the three-dimensional pieces. Your design taste could also have influenced your ranking. Some people like sleek lines (choice a, Quintessential Quail); others are attracted to drama (choice b, Sailfish) or to nature's symmetries (choice c, Nautilus Shell). Even if you had been given more information on each piece and had no preference for the objects depicted, you may have fallen short in this task because you have no experience evaluating artistic glass.

The points I make in this simple exercise are analogous to important considerations in evaluating students. We have often heard that tests are only snapshots. I could hardly evaluate your skills at analyzing art on the basis of that exercise alone. In the same way, we need so much more information than tests can provide before we can judge whether a student is an analytical reader, a creative writer, or an advanced placement–level mathematician. In addition, despite those well-constructed rubrics we use, are we truly objective in our student evaluations—or are we sometimes, as in this glass-ranking exercise, influenced by personal taste?

School leaders can ensure that teachers avoid common pitfalls and hone their skills in using sound assessments by leading a schoolwide effort that focuses on improving assessment practices.

The Real Aim of Assessment

As a curriculum supervisor and college professor in a school of education, my job is to train future teachers. State certification and other standards require that in their portfolios, graduates demonstrate their ability to generate formative and summative assessments that address a variety of learning styles and accommodate the needs of special learners. Graduates often leave their teacher education programs with idealistic visions of the range of assessments they will use to evaluate their students.

But what may really happen to these new teachers when they enter the workforce? Some may have a teacher like Harriet as a mentor. A well-respected veteran, Harriet teaches science to more than 100 high school students. When progress reports are due and she needs more grades, she decides to give her biology students a test, an old one from last year. She realizes that she hasn't covered all the material on this test yet, but she's pressed for time. It's also multiple choice, so it will be easy to correct. The fact is, even seasoned teachers like Harriet, who put serious time and effort into their lesson designs, often resort to more efficient, rather than more effective, assessment instruments.

So how can we preserve the ideals of new teachers when they enter the hectic real world of teaching? And how can we convince veteran teachers that the aim of assessment is to educate and improve, not merely to audit student performance (Wiggins, 1998)?

School leaders can do this by taking three important steps.

Step 1: Start with Coaching

Too often, administrators use a one-size-fits-all approach to professional development, which can lead to teacher annoyance and frustration. If we are going to encourage our teachers to be mindful of addressing the needs of diverse learners, then we should be mindful of the needs of diverse teachers.

Once we have clarified where we want our teachers to be as effective evaluators of student performance, we must then determine where they are along the continuum. Do teachers willingly look for opportunities to improve? Are they open to constructive criticism? Do they realize what an awesome task student evaluation is? Identifying teachers' strengths and weaknesses is essential in designing successful mentoring and coaching strategies.

Many factors contribute to a teacher's competence in assessment. The number of years that the teacher has spent in the classroom does not necessarily correlate directly with an ability to evaluate students. An experienced teacher who does not see a reason to change the way he or she has always graded students will need different guidance than the new teacher who has been trained in designing rubrics but lacks the organizational skills to do so efficiently.

This individualized approach requires time. Administrators need to recognize and believe in coaching as a way to help teachers succeed. It's also an integral part of creating a community of intellectual and self-motivated educators.

Step 2: Question Your Teachers

Once teachers have made a commitment to improve the assessment process, they need some support. Accountability is key to helping teachers grow—and asking questions is a crucial part of that process. For example, as teachers, we let our students know what we think is important by asking such questions as, Did you check your work for spelling errors? Have you looked at this problem from more than one angle?

As school leaders, we also let our teachers know what we think is important by the questions we ask them. Ask your teachers to do the following:

Include sample assessments with their lesson plans.

Every school has a protocol for submitting weekly lesson plans. When I was a high school math teacher, for many years I submitted a plan book the week before I taught the lessons. I conscientiously filled in the boxes with lesson objectives, references to state standards, an outline of lesson activities, and a list of assignments. Often the words quiz or unit test would fill a box. Only once in my long career was I asked to submit a sample of a quiz or test; I was never asked to submit a grading rubric.

Some teachers might react negatively to this request because they will understandably perceive it as yet another pointless thing to do. However, if you do not ask, how will they know it's important? If you collect and code these assessments for one month, you will get a better handle on how teachers evaluate the students in your school. In addition, teachers will more carefully examine their assessment practices.

Highlight verbs in lesson objectives.

Early in my teaching career, I was given a list of verbs from Bloom's taxonomy to assist me in working on a curriculum committee. This was the first time I became aware of a taxonomy of higher-order thinking skills. This document, now worn around the edges, is still an important reference on my desk.

Highlighting the verbs used in the lesson objectives will help both new and seasoned teachers focus on goals that are higher than mere knowledge acquisition. Ask your teachers the following questions: Which levels of higher-level thinking are you addressing in your lessons? What do you really mean byunderstand (Wiggins, 1998)? Do your assessments really provide "acceptable evidence" (Wiggins & McTighe, 2005)?

This last question is crucial to improving student evaluation. If a unit goal states that "the student will be able to show the relationships among the functions of different organelles in an animal cell," having students label the parts of a cell is not acceptable evidence that the students have mastered that goal. Carefully crafting good assessments and the accompanying rubrics takes time and talent. Teachers may need time and training to do this well. Training can begin at a faculty, department, or grade-level meeting. Teachers could share lesson plans and assessments that show correlation between the verbs in unit objectives and the questions asked on the unit test or the rubrics used for grading the unit project.

Another simple and valuable exercise is to ask teachers to highlight the verbs in national and state standards. Many have looked at the content identified in standards; not all have looked at the level of critical thought involved.

Share best practices and help one another.

If formalized peer mentoring and action research programs seem beyond what you can currently ask of your teachers, you can still use regularly scheduled faculty meeting time to let teachers talk. Too often details, such as homecoming issues or fire drill procedures, consume meeting times. There is an unspoken message here about what we value most.

I have also witnessed poor teacher behavior during presentations made by outside experts, either during faculty meetings or special in-service programs. As administrators, we should ask, How can we keep teachers actively engaged in meetings? We preach against the "sage on the stage" model in the classroom and encourage "the guide on the side" approach. Could we also apply this approach to the way we run faculty, department, or grade-level meetings?

Teachers can learn from one another. Experts in the group can lead collaborative growth by sharing their assessment strategies. We do not always need to bring someone in from outside. A simple think-pair-share activity at a faculty meeting can yield amazing results.

Step 3: Focus on Assessment Balance

Some new research-based programs offer helpful assessment tools. For example, Everyday Mathematics includes a tool called a quad that a teacher in any content area can use to develop an individualized assessment plan and chart assessment balance (Everyday Mathematics Assessment Handbooks, 2004). This circle graph, which shows the proportion of different assessment types, consists of four segments: outside tests, periodic assessments, product assessments, and ongoing assessments. Outside tests include district and state assessments and standardized achievement tests, periodic assessments include teacher-constructed quizzes and unit tests, performance assessments refer to portfolio-type items, and ongoing assessments include observations of students as they work on regular classroom activities.

The size of each segment will vary with grade level and teacher. For example, ongoing assessment will be a large piece during a student's early years when teacher observation is most useful for monitoring student progress. Having teachers calculate and construct a quad to include in their teaching portfolios or annual assessment observations achieves two desirable goals: While preparing the diagrams, the teachers must quantitatively examine the importance they give to each type of assessment, and the final visual product gives the evaluator a clear graphic that shows patterns and changes in the way a teacher evaluates students.

A Matter of Will

Art critic and social thinker John Ruskin once said, "Quality is never an accident. It is always the result of intelligent effort. There must be the will to produce a superior thing."

School leaders are responsible for producing this "superior thing"—and for making teachers aware what an awesome responsibility student evaluation is. They can do this by breaking assessment down into a series of measurable benchmarks. And they can start with these three steps.