Long before formal schooling begins, many students—usually from families that are considered educated and that have economic means—have early opportunities for literacy development. Unfortunately, other students struggle with literacy for a variety of reasons. Some are considered unready for school or speak a language other than English. Others have identified disabilities or are impoverished or homeless. By tradition, these students are likely to receive special education, Title I, or English language learner (ELL) interventions.

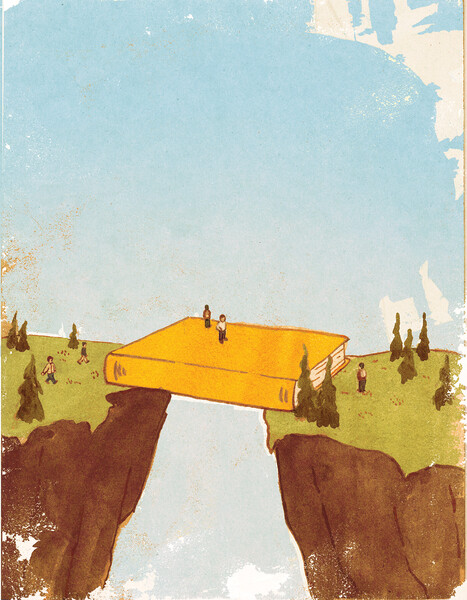

Although it may seem logical that these students would have underlying difficulties learning to read and write, this is not entirely true. Most students have normal cognitive and language abilities and the desire to improve their literacy skills. Too often, a focus on what is wrong—as opposed to a recognition that there's no real reason for students not to learn to read and write—unwittingly creates gaps. It's not the circumstances students bring to school that limit students' growth, but rather their lack of opportunity at school. H. Richard Milner, IV (2010) asserted that focusing on achievement gaps places too much blame on individuals; focusing on opportunity, on the other hand, forces us to think about how systems, processes, and institutions maintain the status quo and sustain complicated disparities in education.

Special education or other remedial programs may seem to offer a positive opportunity for certain students, but these programs can create subtle and inequitable gaps in opportunity. Students may receive fragmented instruction; be taught isolated skills through computers, worksheets, flashcards, or low-level reading materials; and experience covert segregation from an environment rich in language and literacies. Despite decades of reforms and programs to address the needs of diverse students, many students still do not have ample opportunities for literacy development.

What follows are student case studies (drawn from my experiences as a teacher consultant) of traditional mindsets and practices that mask inequity and gaps. Each vignette includes strategies for changing the literacy trajectories for students.

Jeremy's Story: Watch for Signs of Ableism

Jeremy's 1st grade teacher and school principal were concerned about him. They told the special education referral team that Jeremy's vocabulary was limited, which was supposedly impairing his ability to make progress in reading. They thought he might need speech and language therapy and academic support.

However, Jeremy and his father had been homeless for the first five years of his life, living on the streets and in shelters. Jeremy had never been to the zoo, seen farm animals, gone to movies, or had access to everyday household items. Additionally, he was not exposed to school-like literacy items, such as books and magnetic letters. The team members knew they wouldn't be able to provide several years of life experiences for Jeremy, but they knew he needed to learn how to read regardless.

Not unlike racism, ableism continues to be subtle and pervasive in our society. Ableism views insist that a person who is disabled or otherwise has extenuating circumstances must somehow overcome or cure their impairment or differences. "Most people go through life being judged for what they can do, whereas people with identified disabilities are usually first seen through a lens of what they cannot do" (Ramsey, 2004, p. 141). This is ableism in its essence.

There is danger in seeing struggling, special needs, or at-risk students like Jeremy as needing some sort of specialized—and often watered down and segregated—program. Jeremy's team operated from the viewpoint that despite his experience with homelessness, he was still healthy and had normal capabilities. The team began to explore ways Jeremy could learn to read in an inclusive environment.

Jeremy's teacher insisted that a paraprofessional or volunteer read aloud to him every day. During reading instruction, Jeremy and his teacher made books drawing on his life experiences. For example, they created a book about city animals, which was modeled after a book about farm animals. While Jeremy learned about cows, pigs, and chickens, his teacher learned about the small city owls high up in the trees, huge raccoons living in sewers, and squirrels of many colors.

First and foremost, striving toward equity requires the conscious removal of deficit mindsets and a willingness to enter a student's world. Jeremy was learning to read at the same time as he was broadening his academic vocabulary and view of the world.

Jamal's Story: Examine the Assessment-Instruction Connection

Jamal, a student considered "unready" in 1st grade, had not yet started to read. When he was screened for his knowledge of letters, Jamal ranked in the 10th percentile and became eligible for intervention. Every day, he practiced letters with a paraprofessional, his teacher, a reading intervention teacher, and his grandmother at home. The intervention was considered a success. Jamal improved to rank in the 45th percentile by the end of the year, but he still wasn't reading. After two years of intervention and special education, Jamal could name all his letter sounds, put them together in nonsensical consonant-vowel-consonant words, and read the entire Dolch word list. But when his 3rd grade teacher gave him real books to read, he struggled to handle the books, attend to the print, turn pages, and make sense of stories.

The use of assessments, labels, and categories—which often do not paint an adequate picture of students' reading process and progress—inadvertently limits opportunities for students who are otherwise fully capable of becoming proficient readers and effective writers. Moreover, assessments and special education or intervention may carry a medical or pathological mindset, in which the students' circumstances or disorders are assumed to seriously affect their learning. Students who are seen as "failing" or "low-performing" can arbitrarily be placed in separate remediation programs at the cost of an inclusive environment filled with learning language and literacy among their peers.

When Jamal's principal recognized the pitfalls of using assessment scores as a rationale for sending students directly to intervention or special education, he restructured his school to provide increased opportunities for authentic literacy instruction for all students. This included opportunities to listen to adults read aloud, shared reading among peers, independent reading, and small-group guided reading lessons, along with meaningful word work and writing activities.

The principal developed a checklist for educators to document students' access to and growth in each component of literacy instruction. Jamal's teacher eagerly used this checklist to request a reduction of Jamal's resource room time, asked the speech therapist and social worker to incorporate children's literature into their sessions, provided guided reading, and sought a community volunteer to read aloud to him every day. Jamal quickly grasped print concepts and was on his way to becoming a well-rounded reader.

Miriam's Story: View Errors as Strengths

Miriam, a bilingual student, was placed in special education during her elementary years because of her lack of progress in reading. Ever since, she had been bogged down in a program in which she learned letter-by-letter, word-by-word, and rule-by-rule at a time. Throughout middle school, she used an online program emphasizing word recognition skills. By 9th grade, she was seen as unable to access the curricular material required in high school. She was developing a strong narrative that she was not a reader, and she asked about dropping out of school.

In our current climate of standardized testing and worry over frustration levels on benchmarks, there is little room for student errors. For their mistakes and miscues, students are placed in lower-level reading groups, segregated for intervention, or otherwise viewed as having diminished capabilities to learn.

As Walmsley and Allington (1995) write, when students like Miriam are "identified as low-achieving, they are more likely to be asked to read aloud than silently, to have their attention focused on word recognition rather than comprehension, to spend more time working alone on low-level worksheets than on reading authentic texts, and to experience more fragmentation in their instructional activities" (p. 29). Further, when students are removed from their classes or sent to the back of the room with a paraprofessional for intervention or therapy, they receive the message that they do not belong in the larger community until their achievement or behavior has reached an acceptable level.

An English teacher found herself eavesdropping on Miriam reading a 3rd grade book. She noted that Miriam syntactically switched or skipped words as she read aloud. However, when her teacher tactfully asked about her reading process, Miriam apologized and said she was thinking in Spanish rather than reading word-by-word. She shared that she skipped words she couldn't pronounce even though she knew what they meant. She also skipped a word when she didn't know the meaning and wanted to figure it out by reading ahead and using context clues.

It dawned on Miriam's teacher that these "errors" were actually strengths. Miriam's miscues revealed that she was comprehending the text, which is, of course, the ultimate goal for all readers.

Miriam's teacher immediately placed her in a group of average readers to read The Grapes of Wrath (a novel with a 3rd to 6th grade readability level, but a high school interest level). She used a combination of silent and guided reading instruction, audio books, and group discussions (instead of requiring accurate word-by-word reading), and Miriam's motivation soared. In turn, her confidence in reading began to improve.

Rory's Story: Redefine Special Educator and Therapeutic Roles

Rory had a hearing loss and used American Sign Language to communicate. Despite having read erroneous research showing that persons with deafness do not attain more than a 3rd or 4th grade reading level, Rory's 3rd grade teacher knew that he could learn much more than that. She understood that some people with deafness become proficient readers, especially in the current age of access to the Internet, captions, texts, and other technology that support communication. However, she had no experience teaching students with hearing loss and had limited time with Rory in her classroom because he was often out for services and therapies.

When day-to-day instruction in literacy is left to someone other than the general education teacher, the stage is set for exclusionary practices. With lower expectations and fewer opportunities, the cycle of exclusionary practices unwittingly becomes the cause of underachievement.

The viewpoint often held by both special and general education teachers is that special education teachers and therapists are responsible for helping students overcome disabilities in order to access academic instruction. Thus, terms like mainstreaming and inclusion have been attached to the idea of students being "allowed" to enter the school community (Jones, et. al, 2011). It is not necessary to minimize the important role of special education, Title I, ELL, and reading intervention teachers. Instead, we should redefine their positions as supportive to literacy instruction by general education teachers, rather than as a substitute for or precursor to their instruction. In keeping equitable opportunities in mind, they should serve as value-added facilitators for all students.

In seeing that Rory's school day was fragmented and that he was not making adequate progress, his teacher, the school principal, the reading intervention teacher, and special education team members began the work of including Rory in his teacher's literacy instruction. The reading intervention teacher explained that even if Rory was unable to hear most of the letter sounds, phonics was only a piece of the entire reading and writing process. The speech and language pathologist noted that there was no reason Rory couldn't be bilingual in both ASL and English print. The social worker pointed out that Rory reported feeling isolated from his peers and wanted to make friends. Together, they sought recommendations for effective accommodations from a specialist in hearing impairment and created a well-rounded literacy program for him. It was not long before Rory began to see the classroom teacher as his teacher and to view himself as a developing reader and writer alongside his peers.

Toward Full Inclusion

Although different policies and programs have been implemented—even by legal means—to narrow achievement gaps, the bottom line is that the belief systems of the adults immediately surrounding the students matter most. All students should strengthen their language and literacy skills despite the circumstances they bring to school; their circumstances shouldn't be blamed for difficulties in literacy development. By insisting on full inclusion of students from culturally, linguistically, physically, and academically diverse backgrounds, teachers are poised to show that all students belong alongside their peers as viable members of the school community.

Even if current systemic structures maintain a deficiency model of education through the use of testing, ability grouping, and tracking, teachers can still own the instructional decisions that change literacy trajectories regardless of their students' labels or classifications. All students are in different places in their exploration of languages and literacies. And in an equitable environment, all students can achieve growth in learning to read proficiently and write effectively.